Muhammad: Origins of Islam:

Understanding the Qur’an

“Speak to everyone in accordance with his degree of understanding” is a dictum of Muhammad. Traditionally it is understood that there are seven levels of understanding possible in the passages of the Qur’an.

The Qur’an’s major goal then was to provide contemporary guidance to those who wished to live an exemplary life, not only on a societal level but, more importantly, on an interior level. Everything—thought, action, and word—needed to be in harmony if one were to follow in Muhammad’s footsteps. As Fred Donner writes in his book Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing, the Qur’an omits any talk of politics then or in the future: “The Qur’an certainly offers no clear guidance on who should exercise political power among the Believers after Muhammad—or even if anyone should; this simply does not seem to be of interest or concern to the Qur’an. Nor does it provide any indication of how power should be exercised; the only exceptions are moral injunctions so general and vague that they apply to all Believers alike, and so do not address the particular problems of political leadership and its rights or responsibilities in relation to its subjects in any meaningful way.” It does, however, provide detailed rules of conduct for the individual in a multitude of quotidian activities.

For example, in Sura 4 An-Nisa’ (The Women), even read in translation, one gets the sense that this is God’s guide to life—and in intimate detail—because an awareness and connection with the Absolute is the only reason for the Believer’s life. God reckons all things. He is fully conscious of everything we do. He is forgiving and merciful—you don’t have to worry about anyone else’s behavior, worry about your own in the sight of God. God watches every action, every thought, behavior and intention.

The text establishes the requisite mental and emotional attitude, the continuous exercise of self-observation and awareness, that will take the Believer further into the consciousness of God. “You shall remember God while standing, sitting or lying down.” (Qur’an 4:103.) Through haunting repetition one is constantly reminded that:

God is omniscient. Most wise.

God is forgiver. Most merciful.

God is fully aware of everything you do.

God is Pardoner. Omnipotent.

God is Almighty – most wise.

God is in full control of all things.

He has taught you what you never knew.

Jebara writes that Muhammad the Prophet’s audience “needed both intellectual and emotional ways to relate to God.” The names of God—traditionally said to be 99 (the number representing a large number)—were devices to make “God accessible and relatable.” The Prophet saw that they would “help people build their own direct relationship with the Divine,” as they had helped to lead him to his own life of “mentoring guidance, visionary inspiration, and sensitive healing.”

Jebara gives us examples of some of these names:

Ar-Raqib—the Gentle Shepherd who cares for the injured

Ar-Ra‘uf—the Empathetic Soother

Ash-Shafi—the Healer who guides recovery that emerges from within

At-Tayyib—the Applier of Ointment to wounds

Al-Sami—the Attentive Listener who does not judge.

Al-Malik—the Reenergizer (used figuratively for king)

Al-Quddus—the Elevator of the assiduous (used figuratively for holy)

As-Salam—the Restorer of wholeness/Source of Solace (literally, repairer of cracks)

Al-‘Aziz—the Builder of strength (literally, trainer/coach)

Al-Bari—the Refashioner/Architect (literally, transformer of discarded elements)

Al-Hakim—the Wise/Prudent (literally, fuser of weak fragments to make strong ropes).

These names were guides to help people to actively “emulate the Divine” and lead to a closer conscious connection. As Jebara explains “Muhammad was not bequeathing a scripture so much as an experience.” People “needed to recognize that success comes from taking action and embracing their deficiencies as a challenge to improve.”

As a Believer progressed in understanding, so his responsibilities increase: Sura 3:7 “And none receive admonition except men of understanding.” (Tafsir At-Tabari)

From the traditional point of view, “God’s words” were “spoken” directly to Muhammad as they had been to the Old Testament prophets before him. Because it is the language of sacred texts, Hebrew was often considered sacred. In post-biblical times, it was referred to as lashon ha-kodesh, the holy language. And like biblical Hebrew, the Arabic of the Qur’an (the Recitation) is also considered sacred because it is the language through which Muhammad received God’s revelations.

Both texts were addressed to a predominately oral society. They were to be repeatedly read aloud, recited, and their sounds are an essential part of the experience. Both Hebrew and Arabic have multiple resonances of words that have the same trilateral root which affect the listener on multiple levels. Although English has metaphor, allegory etc., as do all Arabic languages, English can only provide a sense of this trilateral root resonance on a far, far simpler level, in certain phrases such as: “looking through the pane” where the pane of glass also can bring up the idea of physical or emotional pain.

The tension between the levels of meaning within a text such as the Qu’ran produces insights in the reader according to his/her capacity to understand. When absorbed simultaneously the reader can see further ranges of significance until the stage could be reached when he/she also finds understanding beyond verbalization. Socratic dialogue, Zen stories and the tales of Nasrudin are examples of other instrumental texts.

The Qur’an refers to Old Testament narratives and prophets such as Joseph, Jacob, Abraham, and Moses and New Testament figures such as Mary, Zachariah and Jesus. But, as Donner points out, “They are told by the Qur’an not because they relate particular, unique episodes in the history of mankind or of a chosen people, but because they offer diverse examples illustrating the basic Qur’anic truths … The lesson of every prophet is that there is an eternal moral choice—the choice between good and evil, Belief and unbelief—faced by all people from Adam on in more or less the same form, and hence simply repeated generation after generation …The apostles and prophets are not, in the Quranic presentation, successive links in a chain of historical evolution, each with a unique role in the story of the community’s development, but merely repeated examples of an eternal truth, idealized models to be emulated.”

The first audiences of the Qur’an were not unsophisticated linguists; these people were passionate about composing both poetry and prose; they excelled in oratory, diction and eloquence. The Arabic language was their pride and joy and they vied with each other in their ability to be fluent and eloquent speakers at competitive events for poetry and oration. Their stories told of their adventures and their valor in warfare, of their amorous exploits and extolled the virtues of their women. Like the ancient Greeks and other oral societies of old, they committed thousands of tales and poems to memory which were passed down by oral tradition from generation to generation. Their pride in their mastery of the Arabic language knew no bounds: they referred to all non-Arabs as “Ajums” (people suffering from a speech impediment).

As noted in The Study Qur’an, the 4th and the 7th revelation came after a long period, which may have lasted 12 or 40 or 50 days. It is further noted that an idolater said to him at that point that “it seems your satan has forsaken you.” According to this account Sura 93 of the Qur’an (The Morning Brightness) was revealed to him at this time, bringing reassurance with it that God had not forsaken him. Further, it was revealed to him that those who experience the care of God have a duty to others “… one who asks for help – do not turn him away;” (Qur’an 93.10) and Muhammad was clearly instructed to proclaim God’s message to the Quraysh: “And the grace of your lord – proclaim!” (Qur’an 93.11) Thus Muhammad became a Messenger whose duty it was to remind his people of what they had forgotten in both religious and social terms.

Jebara writes that “The Qur’an sought to accompany people on their life journeys, offering an evolving experience rather than rigid routine. Just as the hundreds of Divine names provided many access points to God, the Qur’an aimed to make itself accessible to diverse audiences in various life circumstances. It sought to appeal to people’s needs without dismissing their fears and concerns, offering a revolutionary approach to pursuing a fulfilling life.”

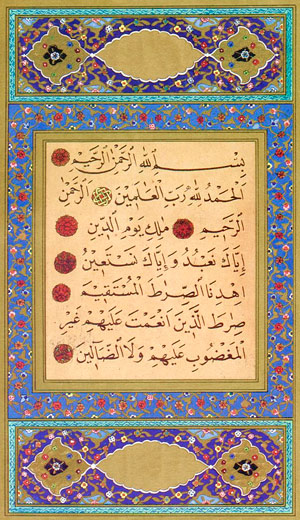

The Qur’an evokes the seeker’s navigation through darkness. Remember, this is the deep darkness of the desert where no artificial light intervenes, but against which stars are seen in all their brilliance. Each chapter of the Qur’an is called a sura, meaning a constellation of stars by which the traveler journeys on, but within which “each ayah or passage is the brightest star in the constellation.” Later, towards the end of his life, Muhammad divided the Qur’an into portions for ease of “recitation and study.”

The prophet received revelations for 23 years until his death in 632.

External Stories and Videos

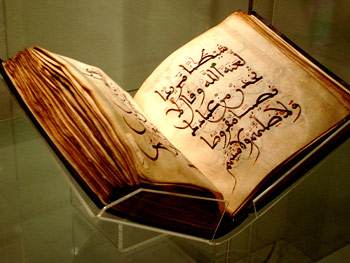

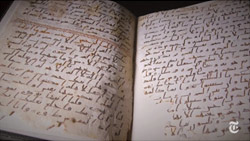

Quran Fragments Found in Britain Are Dated to the Birth of Islam

Dan Bilefsky, New York Times

The fragments appeared to be part of what could be the world’s oldest copy of the Quran, and researchers say it may have been transcribed by a contemporary of the Prophet Muhammad.