Judaism:

The Babylonian Captivity

In exile the Jews learned that Yahweh could be worshipped away from the Temple in Jerusalem, even in a foreign land. He could be worshipped in their way of life anywhere.

In 597 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar the Babylonian king, son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, violently ransacked Judah and took the young king Jehoiachin and 8,000 of his people, including royal and aristocratic families, prisoners to Babylon. Babylon would invade and capture Judah on two more occasions, but it was this first group, wrenched from their homeland and Temple, who created a new Axial Age vision for the Jews.

The Jews were treated well in Babylon. They were allowed to live together in towns and villages along the Chebar River, where they could farm, earn a living, and practice their way of life and religion. They were encouraged in letters from the Prophet Jeremiah to “build houses and live in them, take wives and have sons and daughters, but seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile for in its welfare you will find your welfare.” (Jeremiah 29:5–7)

Like Amos and Hosea, Jeremiah told them to examine their own conduct. Morality and justice were imperative, but the essential element of religion was the individual’s personal relationship between himself or herself and Yahweh. “Can the Ethiopian change his skin or the leopard its spots? Neither can you do good who are accustomed to doing evil.” (Jeremiah 13:23) Human beings follow their desires, not their intellect, so personal transformation depends upon sincerity and a change of heart and, above all, on Yahweh’s help: “I will put My law within them and on their heart I will write it; and I will be their God, and they shall be My people.” (Jeremiah 31.33 NASB1995)

Like Amos, Hosea and Isaiah before him, Jeremiah agreed that the external forms of worship were meaningless, unless, he said, they helped to bring the individual closer to Yahweh.

The prophet Ezekiel, active in the Chebar River area at the time, also saw that the suffering of exile must lead to a deeper personal relationship with Yahweh. Ezekiel emphasized that the “sins of the fathers” will not be visited on the children, and that each person will be judged by God on the basis of his or her own righteousness or sin.

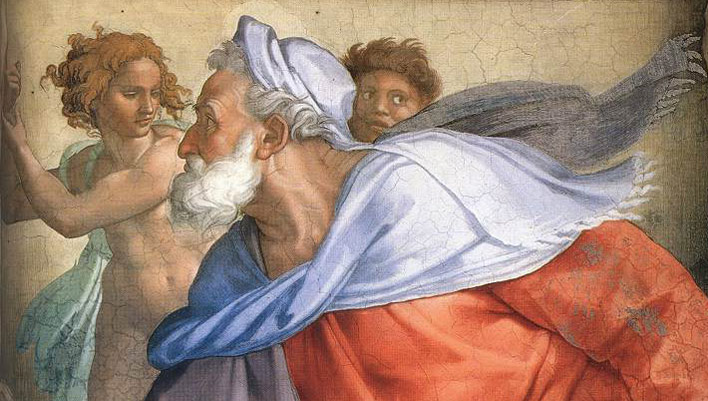

It was while in exile in Babylon—quite possibly as part of an effort to preserve their identity and ensure that they were not assimilated into the Babylonian way of life—that Jewish scholars began to collect and redact the memories, stories and events, some from written and some from oral tradition, that would create what we know today as the Old Testament. With the aid of a new order of “scribes,” they completed the bulk of the first five books known as the Torah (the Teaching). These books trace Jewish genealogy back to Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph and to an ancient place which was the start of all their memories—Eden, a garden watered by the rivers Tigris and Euphrates which according to the Torah was the original human’s birthplace. It was the birthplace of Adam (whose name means “human being”—from the word adama which means “red” and “earth,” perhaps the red earth from which man was created).

The Babylonian Captivity taught the Jews to hate idol worship and to rely on the word of the one true God. It was now available through scribes and scholars who taught and preserved the scriptures and produced the rabbinical literature known as the Mishna (God’s laws allegedly passed down orally and not recorded in Scripture), the Gemara (a commentary on the Mishna and a compilation of accepted traditions), and two volumes that were later added to and combined to form the Talmud. Now with no temple, the Babylonian Jews instituted places for assembly or “synagogues” in which to conduct formal Jewish worship and to provide schools for study and Jewish education.

In 539 BCE, King Cyrus absorbed the land of Babylon and surrounding areas into the Persian Empire, which spread across the Fertile Crescent reaching as far as Greece. The exiled peoples under Babylonian rule were allowed to return home. To some, the Persians, therefore, seemed the bearers of divine forgiveness. Many stayed on in Babylon but others in 538 BCE arrived back to the destroyed city of Jerusalem, to its ruined buildings and fallow fields.

Five Books of Moses (Chumash Torah)

The Torah is often called the Tanakh, which stands for Torah (T), Neviim (N) and Ketuvim (K).

| Current Title & Translation | Original Hebrew Title and Translation | Greek-Latin-English Title |

| B’reshit (“in the beginning”) | Maaseh B’reshit (the account of the beginning) | Genesis |

| Sh’mot (“the names of”) | Yesi’at Misrayim (the going out from Egypt) | Exodus |

| Vayyikra (“…called”) | Torat Kohanim (the law of the priests; the priestly code) | Leviticus |

| Bemidbar (“in the wilderness”) | Pekuddim (counting, census) | Numbers |

| D’varim (“the words”) | Mishneh Torah (the repeated/second law [see Deuteronomy 17:18: “a copy of this law”]) | Deuteronomy |