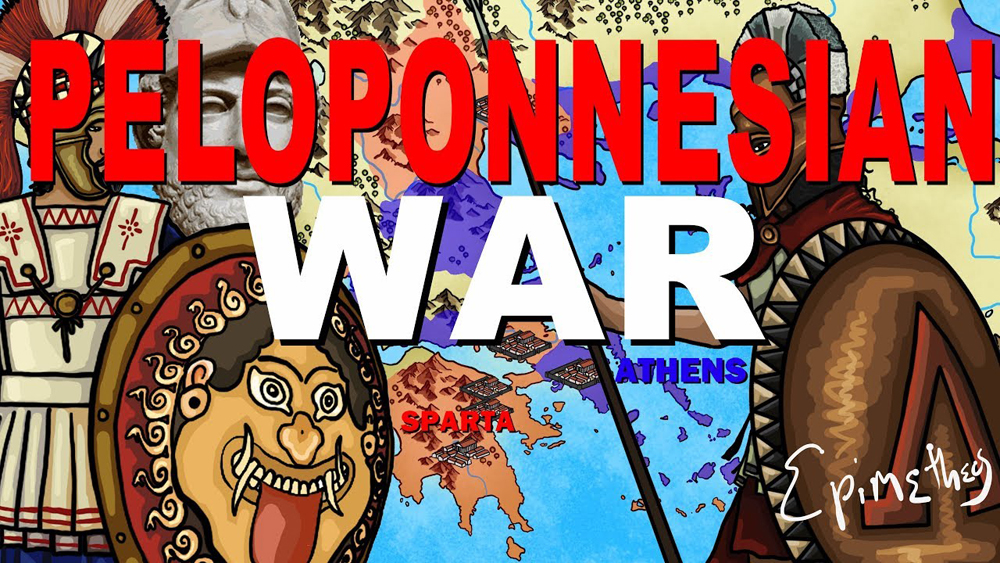

Greece:

The Peloponnesian War 431–404 BCE

By the second half of the fifth century, Athens and Sparta emerged as the two most powerful states in Greece. But now without a common enemy, tensions grew between them, and in 431 BCE they confronted one another, with most of the Greek states joining in support of either state.

This Peloponnesian War was a long and merciless civil slaughter that, over twenty-seven years, produced suffering on a scale previously unknown to the Greeks.

This Peloponnesian War was a long and merciless civil slaughter that, over twenty-seven years, produced suffering on a scale previously unknown to the Greeks. By 404 BCE, Spartans had destroyed the Athenian navy, dissolved the entire empire, marched into Athens, and a pro-Spartan oligarchy ruled the Athenians. Athenian democracy was suspended and a pro-Spartan oligarchy—the Thirty—was installed.

After this, the Greek states remained mired in wars, supported in part by Persian satraps (regional governors) interested in destabilizing Sparta. Resentment against Spartan hegemony united former enemies and even allies. Eventually, in 379 BCE, Athens resumed its position as the leading Aegean power by calling on allies and additional formally pro-Spartan states, and reviving the Athenian League. In 371 BCE the Spartans were defeated at Leuctra in Thebes, which then became the dominant state, but not for long. States allied themselves against Thebes, and from then on continually disputed among themselves until they were overshadowed by the foreign invasion of Philip of Macedon in 338 BCE.

This endless strife continued to be the backdrop to cultural innovation and activity in the polis (city state).

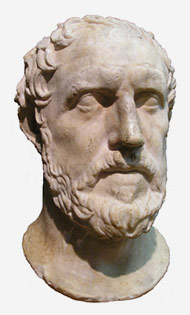

Thucydides and the Beginnings of History (Circa 460–395 BCE)

Almost the entire war was witnessed by Thucydides (465–395 BCE), a well educated member of the Athenian elite and one of the most important and influential historians, whose writings are still studied and discussed in military colleges today.

This Peloponnesian War was a long and merciless civil slaughter that, over twenty-seven years, produced suffering on a scale previously unknown to the Greeks.

Before Thucydides, Herodotus had written history as one would then tell a good story: with a focus on notable events that included heavenly and cosmic intervention.

Thucydides saw that human behavior, not the gods, was responsible for these events. He attempted to analyze events in a way that would help people understand that they were not a result of the gods’ favor or disfavor, but of the actions of individuals. We are all subject to passions, desires and appetites; more often than not, we go to war for irrational reasons, war is a “Harsh master and a harsh teacher,” it destroys our better natures which are nurtured by law and custom. Duress brings out our worst characteristics, and these are evident as war becomes protracted. Fathers kill their sons, neighbors their neighbor, his family and livestock.

Thucydides felt human nature was predictable and education, religion, government and family were ways to help us rise above our natural selves.

He felt that the power of Athens had alarmed the Spartans enough to be a major cause of the war, and looked for the underlying causes of disastrous events in wartime, such as fear, pride, bad calculations, or indecision. His accounts illustrated the way human affairs always follow the same patterns, among them: that power always seeks to increase; that necessity is the engine of history; that leaders must impose their will on those they lead, and that weakness invites the domination of the stronger entity.

Thucydides felt human nature was predictable and education, religion, government and family were ways to help us rise above our natural selves. People will behave in the same way under the same circumstances unless it is shown to them that such a course, in other days, ended disastrously. Athenians lost because they were incompetently led by people who, hungry for power and unscrupulous, misunderstood the strength of the Persian influence, and were undermined by their own greed and hubris.