Jesus: Origins of Christianity:

The Church that Paul Built

Paul’s version of Christianity was uniquely his own, very extreme and very different from that of the Apostles in Jerusalem. Since, as far as we know, the first followers of Jesus kept no written records of the sayings and doings of Jesus and the community in Jerusalem had all but disappeared, it was the Gentile churches started by Paul that survived.

“His marketing skills, his extraordinary powers of communication, his constant contact with individuals from different Christian communities and his habit of issuing written advice and direction in his letters gave Christianity its corporate unity and enabled it to develop into a highly organised and disciplined state within the State.”

The Marketing of Christianity: The Evolution of Early Christian Doctrine, The Institute for Cultural Research

Thirteen of the New Testament books are said to have been written by a man who was known as a fanatical opponent of the early followers of Christ, his life devoted to persecuting them for their blasphemous claims against Mosaic Law. Yet his letters are the earliest writings on Jesus’s life, some written in the 50s, only twenty years after the crucifixion.

Saul was a Jewish Pharisee, well educated, highly intelligent and extremely energetic. Growing up in Asia Minor, in what is now Turkey, his mind was filled with complicated cultural and religious ideas from both the Greeks and the Jews. Though these were often contradictory and irreconcilable, they would both influence his later vision of Christ and the Christian church. But in these early days he, with a number of Jewish fanatics, relentlessly hunted the followers of Jesus, obsessed in their hatred and inexorable in their persecution of them.

In a particularly violent episode, he was witness to the savage murder of Stephen, one of the first deacons of the early church in Jerusalem and considered its first martyr. Stephen was falsely accused of blasphemy against the Law of Moses at a time when Jewish law permitted death by stoning for blasphemy. According to this passage in Acts of the Apostles,

“… Stephen, full of the Holy Spirit, looked up to heaven and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘I see heaven open and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God.’

“At this they covered their ears and, yelling at the top of their voices, they all rushed at him, dragged him out of the city and began to stone him.

“Meanwhile, the witnesses laid their clothes at the feet of a young man named Saul. While they were stoning him, Stephen prayed, ‘Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.’ Then he fell on his knees and cried out, ‘Lord, do not hold this sin against them.’ When he had said this, he fell asleep.” [Acts 7:55 NIV]

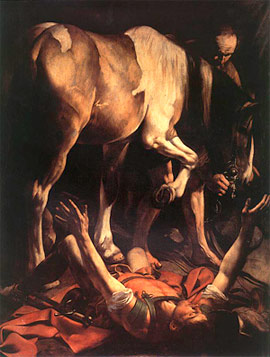

One day following this incident, while traveling from Jerusalem to Antioch seeking out another group of Jesus’s followers, Saul had a vision. Modern psychologists and medical doctors have described it as symptomatic of an emotional overload leading to what William Sargant in Battle for the Mind describes as “ultra-paradoxical behavior where one’s beliefs are precisely reversed … Anger may be no less powerful an emotion than fear in bringing about sudden conversion to beliefs which exactly contradict beliefs previously held … A state of transmarginal inhibition seems to have followed his acute stage of nervous excitement. Total collapse, hallucinations and an increased state of suggestibility appear to have supervened … only after three days did Brother Ananias come to relieve his nervous symptoms and his mental distress, at the same time implanting new beliefs.”

Others have suggested that this and other ecstatic visions Paul reports may well have been symptoms of temporal lobe epilepsy.

All of his fanaticism and energy, previously directed against the Jesus movement, was now directed for the Jesus movement.

More recently, William Hartmann, co-founder of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, reports that Paul’s experience on the road to Damascus closely matches the effects of an exploding meteor, similar to the recent Chelyabinsk incident.

According to Paul’s own account, however, Jesus appeared before him and asked why he was persecuting his followers. Paul was greatly moved by this incident and came to view it as the most important experience of his life. All of his fanaticism and energy, previously directed against the Jesus movement, was now directed for the Jesus movement. He believed he had a divine spirit which enabled him to understand the depths of the spirit of God. He defended his position as an apostle with the early brethren because he had seen Jesus in a vision.

Paul is thought to have initially concentrated on converting Jews, at least for a time, especially Hellenized Jews of the diaspora. Scholars show that the entire Jewish population of the Near East, North Africa and Europe declined from about 5–5.5 million in 150 CE to about 1–1.2 million in 650 CE. At least part of the reason for such a precipitous decline likely had to do with Jews being absorbed into Christianity.

But Paul was also instrumental in bringing the Christian message to Gentiles. His version of Christianity was uniquely his own, very extreme and very different from that of the apostles in Jerusalem. He believed the goal of religion was not attainable through observing the Jewish Law. For him death and resurrection of Jesus made the Mosaic Law unnecessary—he saw it now as a temporary measure which had been replaced—superseded by faith in Jesus Christ. Through “justification by faith in Jesus Christ,” the guilty (sinful) person becomes freed of guilt. Paul considered obedience to the Laws of Moses (reliance upon one’s self as the Jewish Axial sages had commended) wrong and ineffective. He reasoned that if righteousness could come through the Law, it would mean that Christ had died in vain. He believed that Christ had redeemed us from the Law through his death and resurrection. Paul’s emphasis was not on what Jesus taught, nor only that he was the true Messiah, the Son of God, but most importantly that by his death and resurrection our redemption and salvation was won. What was important was to do good works and have faith in Jesus Christ.

Stephen K. Sanderson, in Religious Evolution and the Axial Age, sums up Paul’s gestalt, quoting Barrie Wilson, How Jesus Became Christian: “The Christ movement was led by Paul. He reconceptualized Jesus as both a man and a divine being whose message was religious and nonpolitical. He was sent by God to establish a new kingdom, but this was not a kingdom of the earth. It was a kingdom of Heaven in which those who believed in him would have everlasting life. For Paul, Jesus was Christos, that is, Lord. Paul had no interest in establishing a separate Jewish state. His focus was exclusively on a ‘dying-rising-savior-God-human.’ This is the Jesus that Christians know today. But since this was not the historical Jesus, Wilson deems the term Christianity to be a misnomer. The more accurate term would be ‘Paulinity.’ ‘What we have in Christianity is Paulinity. . . . It is a Hellenized religion about a Gentile Christ, a cosmic redeemer, and it is through that perspective that the later gospels are read. It is not the religion of the Jewish Jesus, the Messiah claimant and proclaimer of a Kingdom of God. That religion . . . eventually died out.’.”

He believed that Christ had redeemed us from the Law through his death and resurrection.

Paul was utterly convinced that he had been divinely chosen to teach the Gentiles, and did whatever it took to convert as many as he could. His beliefs often put him at odds with the Church in Jerusalem, but he believed that Jesus would return at any moment, that time was running out and they had to act quickly. As time went on and Jesus did not return, Paul was forced to change his message, telling his followers that Jesus would indeed return, but only when enough Gentiles converted to belief in Christ.

Many in the Church at this time not only rejected Paul’s preaching as misguided and wrong, but denied his credentials as an apostle.

He admonished his followers for listening to other followers of Jesus preaching a different message and spoke of his personal sacrifice in passionate terms: his outstanding service, beatings and imprisonment. He boasted of visions and revelations of the Lord and told his followers that if his message seemed veiled, it was because they were blind and lacked faith. He alluded to allegations, including the charge that he was out of his mind. If he was out of his mind, it was on behalf of God.

Many in the Church at this time not only rejected Paul’s preaching as misguided and wrong, but denied his credentials as an apostle. But the fanatical Paul defended his highly personal version of Christianity; again and again he would stress that it was faith which made a man righteous: “…believe in God who raised Jesus the Lord from the dead, after Jesus had been put to death for the sins of the believers and was resurrected for their justification,” quotes Samuel Sandmel in Judaism and Christian Beginnings. To those who were anxious about being punished for their past sins, he gave elaborate assurances that those who had faith would be saved.

Paul’s letters along with biographical details of Jesus from the Old Testament … provided a foundation for the early Gospel writers.

Paul felt pride in his unique doctrine and the developing Church accepted many of his ideas, including the nullification of the Mosaic Law. Paul believed that direct knowledge of God was unattainable, but that we can only know God through Christ—man was helpless and unable to affect his own salvation and could only be saved by Christ’s divine grace.

To the Jews I became a Jew in order to win Jews; to those under the law I became as one under the law (though not myself being under the law) that I might win those under the law. To those outside the law, I became as one outside the law (not being without law toward God, but under the law of Christ) that I might win those outside the law. To the weak I became weak, that I might win the weak. I have become all things to all men, that I might by all means save some. (1 Corinthians 9:20–22 RSV)

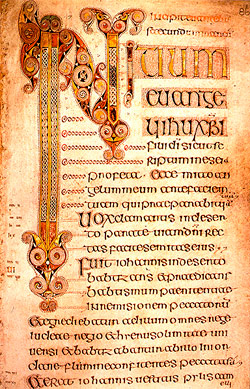

Since the first followers of Jesus kept no written records of the sayings and doings of Jesus and the community in Jerusalem had all but disappeared, it was the Gentile churches started by Paul that survived. Paul’s letters along with biographical details of Jesus from the Old Testament (and to a lesser extent oral tradition) provided a foundation for the early Gospel writers. Mark’s Gospel is strongly influenced by the teachings of Paul. Matthew and Luke are based on Mark, but also use another hypothetical source referred to by scholars simply as “Q.” John’s Gospel differs significantly from the three synoptic Gospels.

Each of the Gospels reflects the environment and preoccupations of the author as well as the message he was trying to convey to his followers. Designed to inspire faith in members of the Church, they were not written to be taken literally. The fact that they did come to be taken literally is now well known.