Muhammad: Origins of Islam:

The Community of Believers

Just as the first followers of Jesus did not think of themselves as part of a new religion, the original community around Muhammad did not either, but rather one akin to the Hanifs—they sought the pure form of monotheism and called themselves the “Believers” (mu’minum).

Prophets and spiritual teachers are not born in a vacuum. The influences and practices of contemporary and historical thinkers and prophets fuel their reactions to the world around them. Jesus, for example, was likely influenced by the theological and ethical teachings of Jeremiah and Hillel, the latter died in his youth and both prophets’ views were at the time, well known in the area.

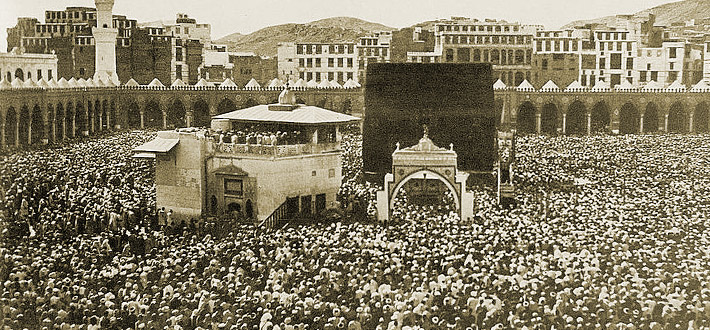

The distance from both empires enabled beliefs in the Arab Peninsula to evolve and flourish independently, especially in Mecca. According to Professor Fred Donner, by the sixth century paganism was receding in the face of the gradual spread of monotheism.

Hanifism arose in Mecca and spread throughout the Hijaz. Its members “turned away” from idolatry, seeking to follow the original, essential Truth, the true monotheism of Abraham (Ibrahim), before polytheism, and before the establishment of either Judaism or Christianity.

In Hanifism we find a key to Muhammad’s prophetic inspiration. Says Barnaby Rogerson, “As Muhammad grew in wealth and wisdom he joined a select group of thinkers in Mecca known as the hanif, the seekers. The hanif searched for a coherent religious identity for the Arabs, a clear doctrine to replace the welter of deities and the shambles of blood sacrifices held around the temple at Mecca. They focused their attention on the all-encompassing father god Allah whom they freely equated with the Jewish Yahweh and the Christian Jehovah.”

“The hanif searched for a coherent religious identity for the Arabs, a clear doctrine to replace the welter of deities and the shambles of blood sacrifices held around the temple at Mecca.”

The Hanif regularly spent some of their time away from the polytheist environment and made retreats to nearby hills to meditate, contemplate and pray, as did Muhammad. One such hill was Hira—the location where Muhammad would receive what is known as his first revelation.

The Qur’an has several entries that speak of the Hanif, and clarify their viewpoint:

22:31 Be hanif in religion towards Allah, and never assigning partners to Him: if anyone assigns partners to Allah, it is as if he had fallen from heaven and been snatched up by birds, or the wind had thrown him into a distant place.

2:135 They say: “Become Jews or Christians if ye would be guided (to salvation).” Say thou: “Nay! (I would rather) the religion of Abraham the true [Hanifan] and he joined not gods with Allah.”

3:67 Ibrahim [Abraham] was neither a Jew nor a Christian but a ‘Hanif’, a Muslim, one who is not among the idol-worshippers.

According to Prof. Donner in Muhammad and the Believers, the Qur’an uses mu’minum to describe the early community around Muhammad far more frequently than it does the term Muslim. “A number of Qur’anic passages make it clear that the word ‘mu’min’ and ‘muslim’, although evidently related and sometimes applied to one and the same person, cannot be synonyms. For example, Q 49:14 states, ‘The Bedouins say: “We Believe” (aman-na). Say [to them]: “You do not Believe; but rather say, ‘we submit’ (aslam-na), for Belief has not yet entered your hearts.”’” Here ‘Belief’ seems to mean a more advanced stage of a person’s spiritual journey—akin to knowing or understanding—than “submission” (islam), which is the initial step.

These Believers differentiated themselves from polytheism in all its forms. The one belief that there is only one God was crucial. Thus, Christians who believed in the Trinity would be excluded: “Those who say that God is the third of three, disbelieve; there is no god but the one God …” (Qur’an 5:73). Hence, for example, Christians from communities who had originally fled persecution in Byzantium for refusing to believe in the Trinity were certainly welcome, and we know that Jews were, too. Christians who followed the Gospels, Jews who obeyed the laws of the Torah and converts from paganism who obeyed the injunctions of the Qur’an would all be included.

Christians who followed the Gospels, Jews who obeyed the laws of the Torah and converts from paganism who obeyed the injunctions of the Qur’an would all be included.

This ecumenical community was perhaps easier to achieve since the majority in the community would have been illiterate, and most likely only the most basic ideas were held among them. “It is fair to assume that most of the early Believers probably knew only the most basic and general religious ideas we today can find articulated in some detail in the Qur’an. That God was one, that the Last Day was a fearful reality to come (and perhaps to come soon), that one should live righteously and with much prayer, and that Muhammad was the man who, as God’s apostle or prophet, was guiding them in these beliefs,” writes Donner.

However, one of the well-known sayings attributed to the Prophet is: “Speak to everyone in accordance with his degree of understanding.” It would not be surprising to find that Muhammad, like Jesus before him, had a circle of people with whom he conversed who were able to understand him in more depth. According to Idries Shah, “There was, too, a well-established belief among the general public that Muhammad had had a special relationship with other mystics, and that the devout and highly respected ‘Seekers of Truth’ [Tulab el Haqq] who surrounded him during his lifetime might have been the recipients of an inner doctrine which he imparted in private. Muhammad, it will be remembered, did not claim to bring any new religion. He was continuing the monotheistic tradition which he stated was working long before his time.” (Idries Shah, The Sufis)

The community of Believers strove to live a pious life. They saw this life as a preparation in a sense for the Last Day or Day of Judgment; it should be lived in obedience to God’s word as now laid out in the revelations of Muhammad. They believed that throughout man’s history God has, from time to time, revealed his intentions to a series of messengers or prophets of whom Muhammad was the last.

Their steps towards inner purity included prayer, charity, fasting and pilgrimage. Distractions from the path of piety could include even family: “wealth and sons are the ornaments of the nearer life; but enduring works of righteousness are better before your Lord…” (Qur’an 18:46), a passage that is somewhat reminiscent of a saying of Jesus from the Gospel of Thomas. In another passage the Qur’an appears to contradict it: “O you who Believe, do not forbid the good things that God has allowed you,” (Qur’an 5:87) but the passage goes on to say: “nor go to extremes, for God does not love those who go to extremes.” Their piety was to be always with them as a source of balance and harmony, part of their everyday life. They were to be: “In the world, not of the world.”

After the Prophet’s Death

In the last years of his life Muhammad solidified his military and political situation. Following the conquest of Mecca in 630 he no longer needed to make alliances with pagan communities in order for the community of Believers to survive and grow. Now tribes wanted to become allies and could do so once they declared their belief in the one true and only God and contributed taxes as a token of their commitment. So the community grew in size and complexity, spreading from western Arabia as far as Yemen in the south, to the east and throughout much of northern Arabia as well.

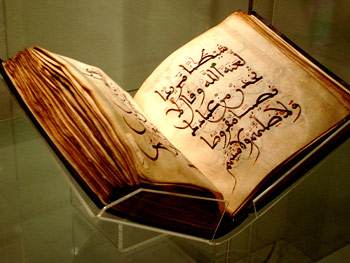

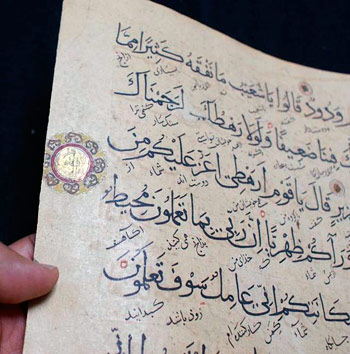

The history of the collection and codification of the text of the Qur’an is confusing and contradictory. Some sources suggest that the recitations were stored in the chest of the companions, and parts of it were written on leathery sheets, white stones, palm’s sheets and ostrich bones. Others disagree, and their research indicates that Muhammad’s revelations were not gathered into the single source we know today as the Qur’an until after his death. One historical tradition holds that the Prophet dictated some revelations to Zayd bin Thaabit and other scribes, while others were remembered and repeated by his closest followers, who learned them by heart.

Shortly after Muhammad died in 632, Arab tribes revolted against the State of Medina. After the bloody Battle of Yamamah, in which a large number of those who had committed the Qur’an to memory perished, recording his words became a more urgent task. The Caliph Abu Bakr assigned the task to Zayd, who, it is said, collected the revelations “from pieces of papyrus, flat stones, palm leaves, shoulder blades and ribs of animals, pieces of leather and wooden boards, as well as from the hearts of men.”

It is possible that the documentation of Muhammad’s revelations may not, at the time, have been seen as the most important activity, because for them, as for many early monotheistic communities, time was running out: the Day of Judgment was approaching, so spreading the crucial tenet of salvation, “there is no god but God,” may well have been seen as their primary concern and duty.

Within ten years of their Prophet’s death the Believers had spread their idea of monotheism to Syria, Iraq, Persia, and Egypt, moving over the next three decades into parts of Europe, North Africa and Central Asia.

Within ten years of their Prophet’s death the Believers had spread their idea of monotheism to Syria, Iraq, Persia, and Egypt, moving over the next three decades into parts of Europe, North Africa and Central Asia.

The still prevalent idea of Islam being a religion of violence dates from the Middle Ages, when the conflict between the West and East and invasions such as the Crusades produced vicious polemics against Islam.

Archaeological evidence challenges the view that Islam’s expansion was primarily by the sword: many churches, some still standing today, were built in lands whose occupation by Islamic activists pre-date their construction. Scholars point out that if Islam’s goal was to eradicate all other existing faiths in favor of forced submission to their own, these places of worship would have been destroyed. On the contrary, the evidence shows that in assuming control of towns and villages a peaceful approach of integration was the preferred method by which the Believers’ message was spread. Communities were adjured to live sufficiently righteous lives and accept the “oneness of God” and to pay taxes to the ummah. Known to the Believers as the “People of the Book,” adherents to other monotheisms were allowed to maintain their own faith without fear of persecution.

By the time of the third Caliph Uthman (644–656), differences in reading the Qur’an in the many dialects of the Arabic language became troublesome, and he was urged to “save the Muslim ummah before they differ about the Qur’an.” Uthman asked a team of companions led by Zayd to collect and compare all available copies and oral versions of the revelations and to prepare a single, unified text. Copies were sent to the main provinces and people were told to burn earlier versions in order to eliminate variations or differences, though many, including key people, refused to do so.

The new young Believers and people in these new communities had no memory of the Prophet himself, so piety became routine and less personal, and guidelines needed to be standardized and written down. Eventually, about seventy-five to one hundred years after the Prophet’s death, the community members started to identify themselves as a different religion. They became Muslims.

Eventually, about seventy-five to one hundred years after the Prophet’s death, the community members started to identify themselves as a different religion. They became Muslims.

During the next few centuries, while Islam solidified as a religious and political entity, a vast body of exegetical and historical literature evolved to explain the Qur’an and the rise of Islam, the most important elements of which are sunna, or the body of Islamic social and legal custom; sira, or biographies of the Prophet; the tafsir, or commentary and explication of the Qur’an, and the hadith, or the collected sayings and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad.

To decide which of the sayings and deeds were authentic, hundreds of thousands of sayings and stories ascribed to the Prophet were gathered together. Scholars such as Imam Bokari, Ibn Rustam and Asim Ibn Ali spent decades investigating and testing texts for accuracy. Bokari reviewed over 600,000 entries, of which he selected as incontestably correct only 5,000. Those that were deemed by these scholars as authentic were collected and called hadiths or traditions. Like the Gospel of Thomas, some of the sayings of the Prophet give us insight into the man and his teaching. Here are some examples from an authoritative collection by Baghawi of Herat in modern Afghanistan, from his Mishkat Al-Masabih:

Sayings of the Prophet

Speak to everyone in accordance with his degree of understanding.”

I order you to assist any oppressed person, whether he is a Moslem or not.

Do you think you love your Creator? Love your fellow-creature first.

Those who are crooked, and those who are stingy, and those who like to recount their favors upon others cannot enter Paradise.

He is not a perfect believer, who goes to bed full and knows that his neighbor is hungry.

By the One who holds my soul in His hand, a man does not believe until he loves for his neighbor or brother what he loves for himself.

You ask me to curse unbelievers. But I was not sent to curse.

My back has been broken by “pious” men.

Desire not the world, and God will love you. Desire not what others have, and they will love you.

Do not ask for authority, for if you are given it as a result of asking you will be left to deal with it yourself; but if you are given it without asking, you will be helped in undertaking it.

Treat this world as I do, like a wayfarer; like a horseman who stops in the shade of a tree for a time, and then moves on.

Trust in God—but tie your camel first.

Die before your death.

The ink of the learned is holier than the blood of the martyr.

On the Challenge of Diversity

Unto every one of you have We appointed a different law and way of life. And if God had so willed, He could surely have made you all one single community: but He willed it otherwise in order to test you by means of what He has vouchsafed unto you. Vie, then, with one another in doing good works! Unto God you all must return and then He will make you truly understand all that on which you were wont to differ. (Qur’an 5:48)

On Knowledge

The Prophet said: “There will be a time when knowledge is absent.”

Ziad son of Labid said: “How could knowledge become absent, when we repeat the Koran, and teach it to our children, and they will teach it to their children, until the day of requital?”

The Messenger answered: “You amaze me, Ziad, for I thought that you were the chief of the learned of Medina. Do the Jews and the Christians not read the Torah and the Gospels without understanding anything of their real meaning?”

From Caravan of Dreams by Idries Shah.