Muhammad: Origins of Islam:

Muhammad the Unifier

Muhammad was tasked to unite not only the Arab tribes but, as he proclaimed again and again, anyone who believes in the One True God. His mystical experience of the Night Journey prepared him for this lifelong task. The record of his experience inspired generations of mystics, including the Christian mystics of the Middle Ages and beyond.

“Muhammad was openly abused on the streets of Mecca. He could no longer preach or pray in public.”

In many traditional teaching stories there comes a point at which the protagonist, having gone through numerous hardships, continues to be faced with so many obstacles, he or she feels that “all is lost,” then a breakthrough—psychological or circumstantial—occurs. People working creatively on a challenging task of any kind have frequently reported experiencing despair prior to a breakthrough. It was so with Muhammed when in 619, the “year of sadness,” he lost not only his wife of 25 years, Khadija, but also his uncle, and protector, the tribal chief Abu Talib. He was not only devastated but found himself in an extremely precarious situation. According to Reza Aslan in No god But God, “The results were immediate. Muhammad was openly abused on the streets of Mecca. He could no longer preach or pray in public. When he tried to do so, one person poured dirt over his head, and another threw a sheep’s uterus at him.”

After his first revelation, Khadija’s elderly cousin Waraqa had warned Muhammad that his task would not be easy and that the Quraysh would eventually expel him from Mecca. Muhammad had been dismayed at hearing this then, but almost seven years later, it looked inevitable. His message was dividing the families of Mecca, appealing above all to the young. The Believers were in essence removing themselves from the traditions of the tribe. Because Muhammad and his followers were seen to be undermining the rituals and values upon which the Quraysh religious and economic foundation depended, a devastating boycott was put upon the whole tribe of Hashim to try to starve the Believers out of Mecca. It seemed inevitable that he and his followers would have to take steps unheard of in the Arab world: they would have to leave their city, their tribe, their clan, leave their family ties and possessions and go off into the desert to establish a new community.

His message was dividing the families of Mecca, appealing above all to the young. The Believers were in essence removing themselves from the traditions of the tribe.

Karen Armstrong writes in Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time that “Muhammad must have felt that he had come to the end of his resources. He was still grieving for Khadijah; his position in Mecca was desperately precarious; and after preaching for seven years, he had made no real headway. Yet at this low point of his career, he had the greatest personal mystical experience of his life.” It appears then that at night he was awakened by the angel Gabriel and conveyed miraculously to the holy city of the Jews and Christians—the Qur’an refers only obliquely to this vision:

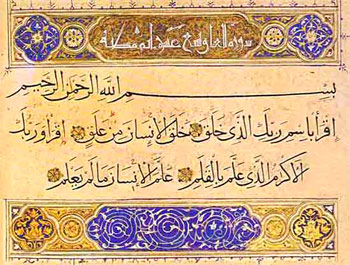

“Limitless in His glory is He who transported His servant by night from the Inviolable House of Worship (al masjid al-haram) to the Remote House of Worship (al-masjid al-aqsa)—the environs of which We had blessed—so that We might show him some of Our symbols (ayat).” (Qu’ran 17:1) Jerusalem is not mentioned by name, but later tradition associated the “Remote House” with the holy city of the “People of the Book.”

Later Muslims, starting with Ibn Ishaq’s eighth-century biography of Muhammad, began to piece together all the fragmentary references to create a coherent narrative. Influenced perhaps by the stories told by Jewish mystics of their ascent through the seven heavens to the throne of God, they imagined their prophet making a similar spiritual flight. According to the historian Tabari, Muhammad told his companions that he had once been taken by the angels Gabriel and Michael to meet his “fathers”: Adam (in the first heaven) and Abraham (in the seventh), and that he also saw his “brothers”: Jesus, Enoch, Aaron, Moses, and Joseph. (Social Origins of Islam: Mind, Economy, Discourse, Muhammad A. Bamyeh)

Ibn Ishaq presents the event as a spiritual experience. He tells of Aisha, the prophet’s wife and daughter of Abu Bakr as saying, “The Prophet’s body stayed where it was, but God transported his spirit by night.” Later historians like Al-Tabari and Ibn Kathir describe it as a physical journey, which many Muslims prefer to believe.

From his youth, the Prophet had been a unifier.

Whatever one’s interpretation, the Night Journey is important. From his youth, the Prophet had been a unifier. The historian Ibn Ishaq, in a memorable story, tells of a reconstruction of the Ka’ba when Muhammad was a boy. A quarrel broke out between the Meccan clans as to which clan should set the Black Stone in place. The solution was to ask the first person who entered the Sanctuary from outside to be the judge. The young Muhammad was the first to do so. He put the stone on to a heavy cloth and had all the clan elders take part of the cloth to raise it and thus share in the task equally.

Now, not only did this mystical experience prepare the Prophet for the Hijra but, more importantly, from then on it is undeniable that “[Muhammad] goes away from tribalism, and finishes not with the tribe but with an embrace of humanity, and an abandonment of the tribal spirit and a reaching out to others. That is the theological meaning of what’s happening,” says Karen Armstrong in the PBS documentary “Muhammad: Legacy of a Prophet.”

“[Muhammad] goes away from tribalism, and finishes not with the tribe but with an embrace of humanity, and an abandonment of the tribal spirit and a reaching out to others.”

Muhammad, the last of the prophets, was tasked to unite not only the Arab tribes, but, as he proclaimed again and again, anyone who believes in the One True God. Anyone can enter into a new community of unity between themselves and a unity with Him. “[God] has established for you the same religion enjoined on Noah, on Abraham, on Moses, and on Jesus.” And “Believers, Jews, Sabaeans or Christians— whoever believes in God and the Last Day and does what is right—shall have nothing to fear or to regret.” (Sura 2:62)

The record of this Night Journey experience inspired generations of mystics to seek a similar experience of divinity.

The record of this Night Journey experience inspired generations of mystics to seek a similar experience of divinity. “It kept the religion open to the mystics, the Sufis, who followed in the steps of Mohammad, men such as al-Ghazzali, Ibn Arabi, Sidi Belhassan and Rumi Mevlana, who for generations would explode the stuffy legalism that threated to constrict Islam and recharge the creed with light, love and a divine scent that came not from this world,” says Barnaby Rogerson in The Prophet Muhammad. These savants and saints would inspire the Christian mystics of the Middle Ages and beyond.

The Hijra

The Hijra, the name for the migration from Mecca to an area called Yathrib (later Medina), took place at night and was a clandestine operation. Sons and daughters left their family homes for a week-long journey through the barren wilderness. The old man Waraqa’s warning had proved correct.

Upon arrival Muhammad allowed his camel to select a place for the first masjid (place for prostration in prayer to Allah, which would later become a mosque) so as not to give any preference to anyone’s choice. This small group of about 70 Believers became the first of a new kind of community (ummah), one whose establishment was commemorated many years later by a uniquely Muslim calendar. That year, 622 CE, became known as the year 1 AH (After Hijra) and at that time the oasis of Yathrib then became celebrated as Medinat an-Nabi, “The City of the Prophet”—Medina.

“Having transferred the Muslim families from Mecca to Medina, he now had to make sure they could survive there.”

“Unlike Jesus or the Buddha, who seem to have been purely spiritual leaders with no temporal responsibilities whatever, Muhammad found himself now head of state,” author Karen Armstrong points out. “Having transferred the Muslim families from Mecca to Medina, he now had to make sure they could survive there.” Establishing the community in Yadith was not going to be easy. Muhammad was welcomed in Medina, and Jebara writes that “Muhammad…gleaned that” the Medinan elders had “grandiose dreams yet remained oblivious to the hard work ahead of them. They assumed Muhammad would miraculously transform their city.” Muhammad’s first revelation in Medina was a reminder that people had to be actively involved in changing themselves in order for their circumstances to change. Here is Jebara’s translation of a verse revealed to Muhammad in Medina:

The Loving Divine will surely not change the state of a people until and unless they change their inner attitude and perspective.