Our Memory and How it Works

From the minuscule amount of information our sense organs gather, we create an Imaginal World, weaving elements of every experience we perceive and pay attention to. These are our “memories,” which are also subject to editing and inaccuracies.

The content of this section, unless indicated, represents Robert Ornstein’s award-winning Psychology of Evolution Trilogy (God 4.0, The Evolution of Consciousness and The Psychology of Consciousness) and Multimind. It is reproduced here by kind permission of the Estate of Robert Ornstein.

As we discussed in the introduction to this website, because 75 percent of the human brain develops after we are born, our individual worlds are not only molded by our families and culture, but by our unique individual experiences. From the miniscule amount of information our sense organs gather from the outside world, we create an Imaginal World, weaving elements of every experience we perceive and pay attention to. These are our “memories.” Smells, sounds, sights combine to make a memorable experience, then each facet is stored throughout the brain in the areas that registered the initial experience and can later be reactivated as a memory. That’s one reason why, for example, a smell can trigger a memory of a total experience.

You’ll recall from the previous article, that the brain’s cingulate gyrus gathers the incoming information both from the outside world and from the body. It compares this information with as many memories as it can and sends the matched information and memory to other parts of the brain where decisions can be made on the most important ones to pay attention to, and what needs to be done next.

We recall memories as stories—as we noted in our section on storytelling—which is why we generally don’t remember much of what happened before the age of four. We don’t have the language skills to be able to tell the story of what happens.

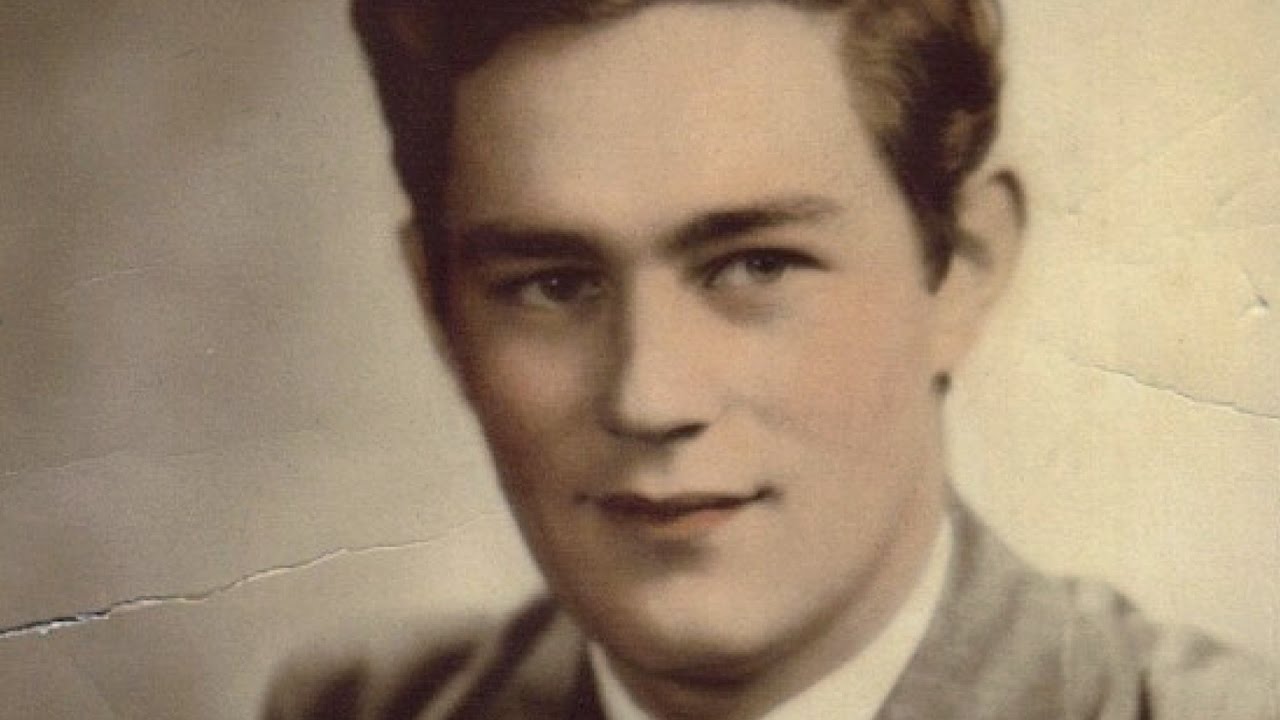

The Strange Case of H.M.

In the 1950s a young man underwent surgery for a severe case of epilepsy. The surgeon, Dr. Scoville, removed his hippocampus (pl hippocampi) located in the temporal lobes of the brain, behind each ear. Henry Molaison, known in the literature as H.M., recovered well except for one thing: he couldn’t form new memories. Although he could improve at skills like tracing shapes in a mirror, he couldn’t remember new people or experiences. His past memories, language, reasoning and sense of self remained intact, but, without his hippocampus, he was trapped in the present, where new meetings and experiences left no trace.

Dr. Daphna Shohamy explains the case of Henry Molaison (better known as “patient H.M.”), whose short-term memory loss following a lobotomy helped researchers to understand how brain structures are related to brain function. (© World Science Festival 2017)

The role of the hippocampi, part of the brain’s limbic system, is involved in spatial memories and in the consolidation of short-term memories to be transferred to the brain’s long-term storage. These seahorse-shaped structures function not only to maintain a record of what happens but are involved in decision-making, acting in a sense as a guide to our future. As Daphna Shohamy, Kavli professor of brain science at Columbia University points out, “patients with hippocampal damage struggle not just with new memories but also with imagining the future. When asked to envision future events—such as plans for next weekend, or their next birthday party—their minds draw a blank. Brain scans of healthy individuals show that retrieving past memories and imagining future ones both engage the hippocampus. Neuronal activity in the hippocampus reflects upcoming possibilities—the future, not just past or present.”

There appear to be three main ways in which the hippocampus supports decision-making: it updates the value of previously learned information; it generalizes the value across related experiences; and finally, by extrapolating from this previous experience, it constructs a new representation.

Such insights suggests that memory may shape decisions even in situations that do not appear, at first glance, to depend on memory at all. Uncovering the pervasive role of memory in decision-making suggests that memory’s primary purpose may be to guide future behavior.

Our Memories Are Incomplete and Inaccurate

For our purposes, we’ll not go into great detail describing the different categories of memory and its workings. For this, we highly recommend Remember: The Science of Memory and the Art of Forgetting by the neuroscientist and author Lisa Genova. But we will cover key aspects that affect how we see and experience the world.

The most important fact to note about memory is that for every step in memory processing—encoding, consolidation, storage, and retrieval—your memory for what happened is vulnerable to editing and inaccuracies.

… for every step in memory processing—encoding, consolidation, storage, and retrieval—your memory for what happened is vulnerable to editing and inaccuracies.

We can’t notice everything that happens, we only encode and later remember certain segments. As we noted above, these segments will contain only the details that were selected by our biases and captured our interest. Not only that, but whatever we remember is vulnerable to editing. It can be changed by a word, a photograph, an association or even a mere suggestion. It can be influenced by how we feel when remembering, we omit bits, reinterpret parts, and distort others in light of new information, context, and perspectives. These new elements overwrite the earlier recollection, just like hitting “Save” on a file in Microsoft Word. The new updated version of that memory is now the only one available.

Lisa Genova cites one study in which researchers asked subjects to share any memories they had of the video of the hijacked plane that crashed in Pennsylvania on September 11, 2001. People were interviewed and then given a questionnaire to test what they remembered. Thirteen percent offered detailed memories of the video during the interview, and 33 percent reported specific memories in the questionnaire. But 100 percent of these memories were false. We have footage of the planes that crashed in New York City and Washington, D.C., on 9/11, but there is no video of the crash in the field in Pennsylvania. These folks believed they remembered details from a video that doesn’t exist.

How Reliable Is Your Memory?

In the video above, psychologist and memory specialist Elizabeth Loftus explains how our memory is vulnerable to contamination via misinformation. With many vivid examples from multiple situations, she clearly shows that “We cannot reliably distinguish true memories from false memories. We need independent corroboration.” (© TED.com 2013)

Have you ever lost your car or misplaced your keys, or walked into a room and not remembered what you’re there for? A lot of us in that moment start to think, “Something’s wrong. This isn’t normal, is it early Alzheimer’s?” but Lisa Genova says actually, it is normal. Since we tend to act in these instances without paying attention, we fail to create a memory in the first place! As she says, “If we want to remember something, above all else, we need to notice what is going on. Noticing requires two things: perception (seeing, hearing, smelling, feeling) and attention. You can only capture and retain what you pay attention to.”

Knowing that we remember only what we pay attention to, means that we have some control over what we remember. We can deliberately avoid remembering events or situations we find unpleasant, at least until their emotional hold on us disappears. And, as Genova says, we can choose to “look for magic every day, if you pay attention to the moments of joy and awe, you can then capture these moments and consolidate them into memory. Over time, your life’s narrative will be populated with memories that make you smile.”

Childhood Amnesia

Humans typically cannot remember events occurring during the first three years of life. This phenomenon, given the name “infantile amnesia” by Sigmund Freud, has intrigued scientists for more than a century. Do people not remember experiences from infancy because the brain is too immature to form memories, or are these memories formed and then forgotten? This seemingly simple question has been difficult to answer given the technical challenges of studying the infant brain. Tristan Yates, a neuroscientist at Columbia University in New York City and her team used brain scans of 26 young children aged four months to two years to find out. They found that the hippocampus—a seahorse-shaped region of the brain that is involved in memory—begins to encode individual experiences as early as one year of age. This challenges a long-held belief that infantile amnesia is due to an immature hippocampus incapable of forming memories. Instead, it suggests that the memories are there, but they become inaccessible as we grow older. This implies that immaturity of post-encoding processes, such as memory consolidation or retrieval, is a more likely explanation for infantile amnesia.

“One really cool possibility is that the memories are actually still there in adulthood. It’s just that we’re not able to access them,” says Yates.

External Stories and Videos

How your memory works — and why forgetting is totally OK

Have you ever misplaced something you were just holding? Completely blanked on a famous actor's name? Walked into a room and immediately forgot why? Neuroscientist Lisa Genova digs into two types of memory failures we regularly experience -- and reassures us that forgetting is totally normal. Stay tuned for a conversation with TED science curator David Biello, where Genova describes the difference between common moments of forgetting and possible signs of Alzheimer's, debunks a widespread myth about brain capacity and shares what you can do to keep your brain healthy and your memory sharp.