Temperament: Dispositional Differences

in Human Nature

Temperament is the core pillar of individuality. It describes a person’s predisposition to respond to specific events in a specific way, and refers to the style rather than to the content of behavior.

The content of this section, unless indicated, represents Robert Ornstein’s award-winning Psychology of Evolution Trilogy (God 4.0, The Evolution of Consciousness and The Psychology of Consciousness) and Multimind. It is reproduced here by kind permission of the Estate of Robert Ornstein.

Temperament is the basic rootstock of individuality, our basic shape. It is more general, more basic than is personality. It describes a person’s predisposition to respond to specific events in a specific way; whether one tends to do everything slowly or quickly, whether one seeks excitement or sits alone, whether one is highly expressive or inhibited, joyous or sullen.

Temperament refers to the style rather than to the content of behavior. We might say that temperament is the “how” of behavior not the “what.”

Temperament refers to the style rather than to the content of behavior. We might say that temperament is the “how” of behavior not the “what.”

In his book The Roots of the Self: Unraveling the Mystery of Who We Are, Robert Ornstein defines three temperamental systems or dimensions—high gain versus low gain, deliberation versus liberation, and approach versus withdrawal. He suggests that there may be more, but that these three give us a basis for analyzing basic differences in people.

We each of us have a set point, like that of a thermostat, at least for these three basic dimensions. The set points of an individual, like the set point of their weight, index different average positions over time and, of course, different people may have different margins of variability in these dimensions. Some people move more than others from high to low gain, from liberated to deliberated, and from approach to avoidance.

There is good evidence that this responsivity to the external world is inherited. For example, extrovert identical twins are more alike than fraternal twins in how sociable they are. What is more, identical twins are much more likely to be similar than are other siblings in whether they are low gain or high gain—whether they augment or reduce stimuli—for example, are easy or difficult to knock out with drugs.

It’s important to realize that temperament is intrinsic. These predispositions in temperament are some of the main routes of adult abilities. A placid baby most often develops into an easygoing teenager. But as we’ve said many times, what you are given biologically can be shaped by what happens to you; temperament doesn’t lock you into a particular personality style just because it is inherited.

High Gainers Versus Low Gainers

The average setting for the input system in the brain stem differs for each of us, and the amount of amplification influences everything we do. Some people, “low gainers,” with low amplification in their nervous system, are starved for stimulation all the time. Others with very high amplification, “high gainers,” are surfeited. The rest of us are somewhere in the middle.

The difference between being outgoing and impulsive and being withdrawn and shy is central to individuality.

The difference between being outgoing and impulsive and being withdrawn and shy is central to individuality. No individual is exclusively one or the other. Just as human beings range from being very short to very tall, with most of us somewhere in the middle, so we are all set somewhere between extreme high and extreme low gain.

You might assume that the person with the brain highly attuned for arousal would be forever looking for action and excitement. But it doesn’t work that way: the quiet types are naturally more aroused than the gregarious ones. This is why introverts tend to go for the quiet life because they already have enough going on inside without having to seek excitement.

Here’s the paradox: those “high gainers” who are highly aroused internally are not the people who are racing around the world, seeking new incitement. By contrast, the outgoing party-animal types who are intensely interested in loud music, who love going out often and at all hours, who enjoy fast driving or parachute jumping, who are often tangled up in complex business or personal dramas, are the ones who have a low-gain nervous system. They need all this excitement and stimulation to keep going. The “low gainers”—whose inner worlds are quiet—need to seek or produce the noise themselves. Thus, many of them have more trouble with the law than do introverts, and they have more business and marital conflicts, do more risky things, and make and lose numerous friends. They’re often divorcing, changing jobs, running rapids, and so on.

Those highly extroverted do better on exams and in elementary school, while introverts seem to do better at university. Introverts usually do better at tasks that require careful attention, while extroverts usually make hopeless radar officers, for example, as their attention quickly wanders from the screen.

High gainers seem to experience the world differently from low gainers; the world is “loud” to high gainers, so they turn the volume down, as it were. One study showed how this works in the brain. When a sudden sound or light appears, we have a characteristic cortex reaction, called an “evoked response.” In this study, groups of extroverts and introverts were exposed to increasingly intense visual stimuli while the evoked responses of their brain wave patterns were recorded. Once the stimulus, either the light or noise, reached a high level, the introverts tended to decrease the intensity of the stimulus that the brain received from the outside. Extroverts, on the other hand, turn their stimuli up.

The reaction to external stimuli may well explain why extroverts do better under pressure since the high level of stimulation that such pressure provides—and that would tip an introvert over the edge—is just what extroverts need to perform at their best. Extroverts have naturally low levels of arousal, so they seek stimulation outside, hence their high interest in parties, sex and dangerous sports.

Positive Approach, Negative Withdrawal

Positive Approach versus Negative Withdrawal describes the degree to which an individual tends to focus more on the positive potentiality of a situation or the negative possibilities. Anyone can see that the tiniest babies show radically different approach and withdrawal tendencies, different levels of gregariousness and shyness.

The decision to approach the good things and to withdraw from the bad is perhaps our most basic internal judgment of all. This dimension is found in decisions made by everything from bacteria to go-go dancers or scientists and contains the basis for countless decisions we make about whether to move closer or to move away.

Surprisingly much of our life is spent making these simple go-or-no-go, get-close-or-go-away decisions. They’re involved in everything – the people we choose to live with, the people we pass in the street, the food we either eat or avoid. They determine threats or the benefits of objects while we navigate the world; they influence decisions about marriage, travel, the future, and so on. This dimension requires the least explication since we are all familiar with basing a judgment on “Is it good for me?” or “Is it bad for me?” and “Do I like it or hate it?” The positive-negative continuum is immediately familiar to us.

Deliberation—Liberation

A third continuum concerns how much an individual deliberates about, and thus regulates, his or her actions or how open he or she is to the spontaneous experiences of the moment. Although, of course, everyone must do both to live, different individuals are set at different points on a scale of how well and how often and in what detail they deliberate about and then control their daily actions.

Deliberation involves regulation of activity, planning, usually a sequence of distinct and separated actions: “First we’ll reserve for the 23rd to the 27th at campsite #290; then we’ll go to a camping store, then we’ll buy some tent poles and check them for size, then we’ll get a tent that fits our car, then we’ll get a road map and plan the best routes…” We use “liberation” to mean spontaneous activity, open to new experiences, and fewer, or no, boundaries between actions or thoughts and feelings, all happening more at once, in the “flow”: “Let’s go to the mountains now!”

The highly deliberated can be thought of, then, as more compartmentalized and with a fairly static structure to their “organization chart.” The liberated may have looser links and boundaries between the different parts of their minds, leading to more communication and sometimes more chaos. Their reactions to the same situation will vary more than would those of the highly deliberated. One group would, if graphically represented, look like an airline meal, with all the different bits in isolated compartments; the other would look like a big stew in which a dash of any seasoning has an effect on everything in it. For deliberators, emotions, even highly felt ones, can be walled off from judgment or from their next job; for the liberated, feelings flow more freely over everything and color all.

The freer, liberated style lends itself to breakthroughs in creative thought. Creativity requires a thinker who doesn’t follow the herd. In most cases, this means that one has lots of ideas that don’t follow the usual sequences, which explains why many people who are thought to be highly creative are also considered unusual. Isaac Newton, for example, spent days locked in his room pouring over the mysteries of the Book of Daniel while he was working on the theory of gravity.

The eccentricity that seems to go with art, creative science, or writing can be expressed in either a high-gain or low-gain way. The painter Francis Bacon would get in the right frame of mind for work by staying up all hours, drinking and having sex as much as possible. Thus liberated, he would paint. Lower gain, but just as liberated from convention, Albert Einstein, while sitting on a streetcar watching a clock tower recede, thought, “If the streetcar were going at the speed of light, I’d see the same time on the clock face forever.” Who would think that speed and time could be related in this way? Not anybody else who had come before him, deliberating along lines they had already soaked up.

We can often recognize where someone sits on the continuum of deliberation-liberation. At the center but slightly toward the liberated side are what we call free spirits, and on the other side of center are the careful sort who plan out each week and every vacation in detail. Further from free-spirithood might be those who are creative in all spheres, who feel free to follow uncharted lines of association and have an “artistic temperament.” On the other side would be those with a rigid accountancy or legal mentality, who work everything out sequentially, logically, in order, where all is checked and balanced. As we move further away, impulsivity and compulsivity would appear on each side, and furthest away would be schizotypal thought and schizophrenia itself on one side and obsessive-compulsive disorder on the other.

Most of us, for most of our lives, mix deliberated planning and openness to the moment, although we all have our set point on this continuum for different activities. In each case, the layers between us and the world are thicker or thinner, more bounded or more open.

Barriers or Boundaries

The psychiatrist Ernest Hartmann, in Boundaries in the Mind, makes a distinction similar to the Deliberation-Liberation continuum. He distinguishes between people who have thick boundaries, who compartmentalize their different experiences, from those with thin ones, whose experiences merge together.

…we all possess inherent cognitive biases ranging from reliance on strict, sequential methods of examining information to an all-at-once manner of thought involving diffuse and loose associations.

In GOD 4.0, the Ornsteins chose barriers rather than boundaries as a better descriptor. This is because barriers can be porous. They note that we all possess inherent cognitive biases ranging from reliance on strict, sequential methods of examining information to an all-at-once manner of thought involving diffuse and loose associations. Where we are on this continuum underlies how open we are to new ideas and experiences, versus being tethered and fixed to doctrinaire interpretations of the saying of venerated ancestors. These biases affect everything from our idea of God, to our religious and political affiliations, to our preference for open versus closed borders of our country.

There’s a distinction between people who keep dissonant thoughts and ideas apart and those that allow them to influence each other. Similar distinctions might be convergent thinkers (linear, logical and systematic) versus divergent thinkers (flexible, creative and explorative); or tough- versus tender-minded people. People also differ in their ability to become fully involved in an idea or mental image – this is called “absorption” and is often assessed by the ease with which one is hypnotized; and in the degree to which information, thoughts and ideas move in and out of consciousness—which is termed “transliminality.”

Thick-barriered and thin-barriered types also show differences in sleep patterns. Thins spend more time in hypnopompic and hypnagogic (half-awake or half-asleep) states as they awaken or fall asleep. Thick barriered people have more clearcut states of waking and stages of sleep (including the vivid imagery of REM sleep and the more thought-like state of NREM sleep) whereas thin barriered people have more in-between states.

Most of us fall somewhere midway, but a look at the extremes on the barrier continuum can make this concept easier to understand. That said, anyone whose barriers are at the extremes is likely to encounter considerable difficulty. Those with exceptionally porous or thin barriers may struggle to separate their personal sense of self from their environment, making them highly variable and emotional. People at the extreme end of the thin-barrier spectrum may have a lot of sensory experiences all at once—including synesthesia, where different senses are coupled so that sounds perhaps are perceived colored or having different shapes. Such people are easily hypnotized, see themselves as having aspects of the opposite sex; have less clear personal space boundaries than other people; they may blend past, present and future; think in shades of gray as opposed to black and white; and experience themselves as belonging to, and identified with, different groups at different times.

Interestingly, although the underlying reasons are subject to a lot of different interpretations (both cultural training and something inherent in female biology have been proposed), females have been consistently found to have thinner barriers than males. This is positively linked to their ability to make connections and is a disposition that most often stays stable across the course of life.

Thin-barriered people are more intuitive and emotional and have more unusual perceptual experiences such as feelings of clairvoyance or premonition. They show interpersonal dependency, social introversion and egocentricity. They are more insecurely attached, more easily reactive, and more easily alienated than are thick barriered people, who are more defensive. Those with thick barriers tend to be detached and are less likely to have close personal relationships. Thick-barriered people are more connected to religiousness, whereas thin-barriered people are more connected to spirituality, and are more able to transcend the small world of everyday consciousness.

People at either extreme of the brain barrier make what statisticians call “Type 1” and “Type 2” errors. A Type 1 error involves concluding that something exists when it doesn’t, or when there’s not really enough evidence to conclude that it exists. Thin-barrier people are prone to make such over-conclusions. Type 2 errors involve denying that something exists even when the evidence is pretty good; those making these kinds of errors stick to what they already know and keep their barriers solid. These two types of errors are the causes of much misunderstanding in life—in marriage, at work, and in politics.

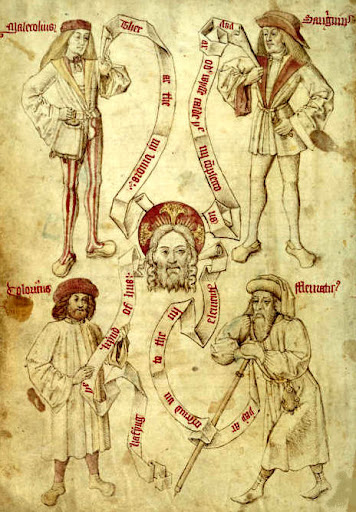

People who adhere strongly to one or another cognitive style have a genetic predisposition to do so. People who abhor social, religious or political change are somewhat prewired (though not hardwired) to be fundamentally conservative: to keep things as they are or as they believe they were in the paradisiacal Muhammadan Caliphate, in the church of the Council of Nicaea, in the colonial world of the original Constitution, or in the days of late 1950s European royalty or even the nuclear families and role definitions of midcentury America. We can observe this cast of mind all over the world today.

Again, neither extreme is ideal. What’s needed is a balance between the two.

Though these different cognitive predispositions—thin barriers versus thick, open versus closed—may be partly determined by our genes, the good news is that people can learn skills to help them move along the continuum.