Featured Book

Moral Tribes

Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them

Joshua D. Greene

Paperback edition 2014

We live in an age of historically declining violence and expanding kindness. But it doesn’t feel like that to most of us. Unprecedented global threats and conflicts demand advances in our ability to coexist peacefully. Joshua D. Greene believes such improvements require changes in our moral thinking and a global morality to help resolve disagreements. Moral Tribes aims to lead us toward these goals using philosophy, science, psychology and neuroscience to illuminate the nature of modern moral disputes, their difference from the types of problems our brains evolved to solve intuitively, and how our different thinking capabilities fit these two types of problems.

For years, the overwhelming consensus was that morality has its origin in religious thought, and that without belief and guidance from a higher source we would revert to the immoral savages we used to be. However, recent studies in animal behavior, developmental psychology and neuroscience have transformed this notion. From observations by Frans de Waal and the findings of Paul Bloom, Robin Dunbar, Matthew Lieberman and others, we learn that our moral behavior is innate; it evolved over millions of years to promote cooperation within our group. Each group has its moral code, which provides a map for how individuals can live successfully within it. Because we were able to make decisions that favored the group over the individual, the human race was able to evolve, adapt and expand as it has.

The Role of the Brain in Moral Decisions

To gain a deeper understanding of human morality Joshua Greene scanned the brains of individuals while they puzzled over philosophical questions such as the famous trolley experiment.

One version, the footbridge dilemma, places you on a bridge, with a clear view of an oncoming trolley about to strike and kill five workers. The only means of preventing their deaths is for you to push another rather large observer off the bridge onto the tracks to stop the trolley; this one death would prevent the deaths of the other five, which would arguably be the best outcome. But most people find this action morally unacceptable, even when increasing the number of lives saved to millions.

Another version, the switch dilemma, poses a similar situation, but the participant can avoid the deaths of the five workers by throwing a switch to redirect the trolley on to a different track—where a single worker will be killed. Most people find this action acceptable.

Why is sacrificing one life to save five acceptable in one instance but not in the other? Greene discovered that we contemplate issues of right and wrong differently in different situations because the neural networks in our brains respond differently depending on the degree of personal involvement in a dilemma. Functional MRI (fMRI) testing reveals that Footbridge type scenarios activate the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) and the amygdala regions of the brain. These areas are associated with intuitive, emotional responses; they are quick, even impulsive. But Switch type scenarios activate the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), an area that is associated with cognitive control, with slower, more deliberative responses.

The neural networks in our brains respond differently depending on the degree of personal involvement in a dilemma.

The switch case seems more acceptable than the footbridge case because of the use of personal physical force in the latter, which by itself ought not seem morally relevant (we sacrifice one life to save five, either way)—but it is psychologically relevant to our dual-process brains. Only 31% would throw off the bystander in the Footbridge case, while 87% would flip the switch. Additional versions of the dilemma reveal more. We would act positively in other versions which save five people through an action whose side effect kills a single person; for example, by opening a trap door to drop him onto the tracks (59-63%); by knocking him onto the tracks in a rush to reach the switch (81%); by throwing a switch to loop away from the 5 victims but killing the other one, stopping the trolley from returning to the main track and the other victims (81%); and by directing a parallel trolley onto a sidetrack where collision with one victim will trigger a sensor stopping both trolleys (86%).

Impact on the Larger Issues

These same kinds of judgments are made between killing as collateral damage vs. killing intentionally, and prescribing palliative drugs which hasten the death of a terminally ill patient vs. prescribing drugs to end the patient’s life. A similar distinction judges harm caused by things we actively do to be worse than harm caused by inaction. This distinction, too, is widely applied; for example, doctors may not cause a patient’s death, but they sometimes may permit them to die. None of these decisions reflect deliberative thought; they are automatic moral judgments.

Even ordinary decisions often involve the dual-process brain, for example deciding between immediate gratification and the “greater good” of future consequences: now vs. later. fMRI experiments with such decisions reveal brain activity like that in the bridge and switch dilemmas. Decisions for immediate reward exhibit increased VMPFC activity that’s absent in the DLPFC-heavy decisions for delayed reward. Similar fMRI results appear when people try to regulate their emotions, such as looking at pictures which typically elicit negative emotions while trying to apply a positive description of the pictured activity—in effect, reappraising the pictures. And similar brain activity appears when viewing pictures of racial out-groups (whites viewing pictures of black people, for example).

Me vs. Us and Us vs. Them

Moral Tribes suggests that the two main problems of modern existence are similarly affected by the dual way our brains are activated. Both these problems are essentially social: they are “Me vs. Us” and “Us vs. Them.”

“Most of morality is about gut feelings,” Greene says. “Our gut feelings enable us to be cooperative, to form groups. But the same gut feelings that enable us to form a cohesive group—that enable people to put ‘us’ ahead of ‘me’—also make us put ‘us’ ahead of ‘them,’ not just in terms of our interests, but in terms of our values.”

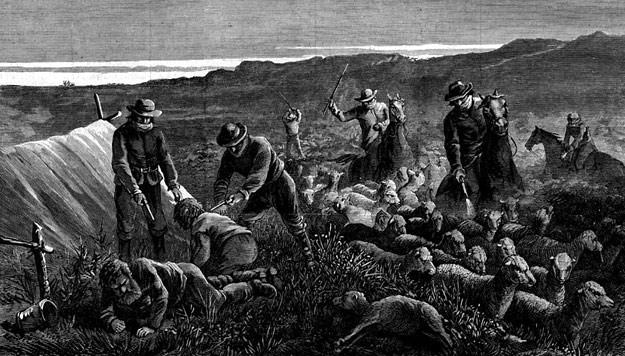

He discusses the well-known tragedy of the commons, in which multiple sheepherders share a pasture but each acts in his own self-interest, eventually over-grazing and destroying the pasture. He argues that this problem is not really tragic because in “Me vs. Us” situations our established intuitive mode of thinking – which he compares to the “point and shoot settings” of a camera – produces emotional responses, such as guilt and empathy that nudge us towards seeking solutions that favor cooperation with the group. But, at the same time, our “point and shoot” responses lead us to solidify the loyalty and strengthen the affinity we feel for our group at the expense of caring for those outside it. Over time each group, tribe and community develops a different moral system as they implement different methods to avert the tragedy of the commons.

The “Us vs. Them” problem is more difficult to overcome as we see everyday among different racial, religious, political and national groups. All groups may want the same things: health, food, shelter, and leisure; and share the same core values of honesty and morality; and even in conflict, our minds work similarly, fighting not just for ourselves but for family, friends, community and our idea of justice. Nevertheless, our specific values and interests may differ from the other groups’, resulting in disagreements as we try to coordinate and solve problems. Here “point and shoot” responses, in which we unreflectively follow our moral instincts, only further complicate our ability to come up with solutions. Differences in interests affect our gut intuitions about what is to be done, because, Green affirms, “our biases are baked into our gut reactions.” Each group’s view of the facts is likely to be colored by its biases, history and commitments; and these may well be incompatible with those of other groups. Greene calls this the tragedy of common-sense morality.

Moral Tribes suggests that if the problem is one where both sides have strong gut reactions that are incompatible—even if, in some abstract sense, they reflect similar values—it can only be solved if, using the camera metaphor, we “shift into the manual mode” and think more reflectively. Psychologically, these two modes resemble emotion and reason. Emotions are automatic—you cannot choose to experience an emotion (though you can choose to experience something likely to trigger one). For most activities, our automatic settings—emotional responses—guide us well. But when we recognize the need for it, our manual mode—reason—needs to be able to override those automatic emotions.

Need for a Common Understanding

Understanding how our minds work will help make wiser decisions, but resolving “Us vs. Them” conflicts also require a way to mediate among competing tribal values and interests. Green says we could base intertribal cooperation on a universal morality—if we had one. But since no universal moral truth has been identified, we must all develop our own by identifying shared values to use as common currency. Again, this task is more difficult than it might seem because moral abstractions (family, freedom, equality, justice, etc.) may be shared rhetorically but interpreted differently by different tribes and individuals within tribes.

Greene proposes that utilitarianism—doing whatever action promotes the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people—may help in this. Espoused by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill in the 18th and 19th centuries, the utilitarian’s thought that all actions should be evaluated by their effects on happiness, not happiness as a collection of things that please us—these specifics are where we inevitably differ—but as the total quality of experience, including family, friends, love, character, avoidance of suffering, etc. Utilitarianism is impartial—no one’s happiness is more important than anyone else’s—meaning not that everyone will be equally happy, but that decisions and actions should aim at maximizing everyone’s happiness. By combining the impartiality of the Golden Rule with the common currency of human experience, utilitarianism provides a means to acknowledge and adjudicate moral trade-offs, so that “happiness” encompasses other values and ultimately means the same thing to everyone. It may not be universal moral truth, but the author feels that this philosophy could be a useful aid to our moral thinking.

All else being equal, we prefer more happiness not only for ourselves, but for others too. But “all else being equal” is a big qualifier: we favor increasing everyone’s happiness, but not if it means accepting the unacceptable (like pushing people onto trolley tracks). Our manual mode may lean toward utilitarianism, since it is designed for flexibility and allows us to consider larger, longer-term goals. It also enables us to weigh consequences, trade-offs and side effects to determine which action will provide optimal consequences, as we seek to identify what policies tend to increase or decrease happiness.

“Optimal” involves two aspects: for whom it is optimal and what optimal means for a particular individual. Although we are not naturally impartial, we can recognize that all people are essentially alike, even to caring most about themselves, their families, friends, and so on. This recognition does not create impartiality but can enable a theoretical preference for impartiality, at least as an ideal. In other words, we do not live perfectly by the Golden Rule, but we understand its appeal, emerging from our automatic moral emotions, our concern for others, or empathy. But we can approach impartiality only through our manual mode, using reasoning and quantitative manipulation to transform our group values into something more objective.

Unfortunately, we often follow the guidance of our automatic emotional morality on critical personal and policy issues like bioethics, end of life decisions, capital punishment, mandatory vaccination, organ donation, abortion, torture, environmental degradation, and war. We tend to reject actions that serve the greater good on such issues not because we have thought carefully and made wise moral decisions, but because our moral alarm bells over or under react to actions or omissions.

The “Identifiable Victim Effect”

Experiments uncover a further limitation of moral emotions: physical distance. We are morally obligated to save a child drowning right in front of us, but most of us feel it’s optional whether we contribute to save starving children somewhere else on the planet. This makes sense, given that the evolutionary history and purpose of our moral emotions was solving the “Me vs. Us” problem: no corresponding advantage accrues from universal empathy. In addition, we are victims of the “identifiable victim effect.” Joseph Stalin is reputed to have said: “The death of a single Russian soldier is a tragedy. A million deaths is a statistic.” And Mother Teresa, “If I look at the mass I will never act.” This aspect of our psychology may well have evolved in order to ensure the survival of our immediate kin, back when we were most likely roaming around in small groups. But in today’s world the consequences of giving in to what psychologists call “the collapse of compassion” – and for that to lead to inaction – can be disastrous.

Obviously, this difference in response is not a reliable measure of difference in moral obligation: it is a product of our automatic moral intuition, which, as we have seen, lacks flexibility and perspective. Utilitarianism offers no clear formula for how we should allocate resources, but just as we would not consider complete selfishness an acceptable moral principle, we would also not find valuing only the welfare of our tribe acceptable. Valuing the happiness of all people equally is an ideal worth striving toward.

Overcoming our Unconscious Biases

Using our manual mode in the right way means that we recognize and overcome our unconscious bias, our tendency to select and value evidence supporting our position over other evidence. Certain “rules” can help with this.

1. “In the face of moral controversy, consult, but do not trust, your moral instincts.”

In personal life, moral instincts can guide us to favor Us over Me. But in controversy, only our manual mode can help in “Us vs. Them” conflicts.

2. “Rights are not for making arguments; they’re for ending arguments.”

Rights and duties rationalize moral intuitions; they have no objective existence, so there’s no arguing over them. “When we appeal to rights, we’re not making an argument; we’re declaring that the argument is over.”

3. “Focus on the facts, and make others do the same.”

To evaluate whether an action is good or bad, we must understand how it’s supposed to work and what its likely effects will be. If we don’t know the former, we must acknowledge our ignorance. The latter we can understand only through evidence.

4. “Beware of biased fairness.”

Even when we think we’re being fair, we unconsciously favor our point of view.

Trying and failing to explain how a policy or course of action would work makes us realize we are out of our depth and moderates our views.

5. “Use common currency.”

Happiness and absence of suffering are what we all seek from our experience, through one means or another, and if we value everyone’s experience equally, we have a common currency of value. Observable evidence is our common currency of fact.

6. “Give.”

Making small, reasonable sacrifices can help others—even those far away—in dramatic ways. Recognizing that we are more responsive to those nearby than to distant, “statistical” strangers, we can make conscious efforts to counter our inherent selfishness, help those less fortunate, and increase the quality of everyone’s experience.

Applying the Rules to Modern Problems

We can see how these rules, outlined in Moral Tribes, could help us develop tactics for dealing with seemingly intractable conflicts. We often hold strong opinions on complex issues without expertise on these issues. We think we understand things that, in fact, we don’t. Experiments show that trying and failing to explain how a policy or course of action would work makes us realize we are out of our depth and moderates our views. So addressing “Us vs. Them” conflicts should start with explaining how different policies are supposed to work, rather than begin with reasons why one is better.

For example, when debating single-payer healthcare or cap-and-trade carbon emissions, if we start with an explanation of the mechanics of the system’s operation, rather than why it is a good or bad idea, we may well temper strong opinions and foster an atmosphere more conducive to negotiation.

Another tactic is avoiding rationalization. Remember that automatic responses are just that—automatic. We don’t understand why we have a particular automatic emotion, but if asked, we will come up with a reasonable-sounding explanation. We don’t use reason to arrive at the moral emotion; we use it to justify having arrived there. Rationalization won’t help determine the best course of action; it will further polarize us. To use manual mode properly, we must recognize rationalization for what it is.

A third tactic is not arguing by appeal to rights or duties. This approach avoids real argument by claiming an action is required by an underlying principle (i.e., “right to life” vs. “right to choose”). Duties are the mirror image of rights: duties say what is required and rights what is prohibited. But appeals to rights or duties end discussions, rather than furthering them. They pretend “the issue has already been resolved in some abstract realm to which you and your tribespeople have special access.”

We don’t use reason to arrive at the moral emotion; we use it to justify having arrived there.

Yet rights do have a place in moral disputes: when a debate is not needed, rights and duties assert the primacy of common sense moral judgments—provided they are truly settled issues. For example, all civilized tribes agree slavery is unacceptable. So, if someone were to argue for slavery, we don’t engage in analysis; we simply assert slavery violates fundamental human rights, ending the discussion. But these situations are rare. Real controversies are not solved through appeals to rights or duties but through careful thought about what results can be expected from what actions.

Valuing the happiness of all people equally is an ideal worth striving toward.

Moral reasoning is difficult, and possibly ineffective, in the face of moral emotion, but over time it can prevail, eventually even changing what moral emotions encompass. Consider that, in 1785 Bentham argued that the law punishing gay sex with death had no utilitarian basis. And in 1869 Mill argued that reason supported women’s rights, despite strong, entrenched feelings to the contrary. Today, these positions are unquestioned parts of our automatic moral emotions.

The Gap

The Science of What Separates Us from Other Animals

Thomas Suddendorf

A leading research psychologist concludes that our abilities surpass those of animals because our minds evolved two overarching qualities.

In the series: Our Mind in the Modern World

- An Ancient Brain in a Modern World

- Our Unconscious Minds

- Maintaining a Stable World

- The Multiple Nature of Our Mind

- Connecting with Others

- Morality’s Long Evolution

- Unconscious Associations

- The Brain’s Latent Capacities

- God 4.0

- Multimind: A New Way of Looking at Human Behavior

- Thinking Big

- Social

- The Weirdest People in the World

- The Righteous Mind

- New World New Mind

- The Mountain People

- The Matter with Things

- Humanity on a Tightrope

- Beyond Culture

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Watch: The Trolley Problem

BBC Radio 4

Is sacrificing one life to save the lives of many others the best possible outcome? Do you draw conclusions from how things are to think about how things should be? There might be a gap in your reasoning.

Strangers in Their Own Land

Anger and Mourning on the American Right

Arlie Russell Hochschild

Concerned about the increasing and seemingly irreconcilable divide in American political discourse, a progressive-leaning UC Berkeley sociologist travels to Louisiana, deep into the heart of Tea Party country. Her goal: to scale the “empathy wall” by getting to know the people, understanding their “deep story,” and finding the places where they might connect.