Axial Age Thought:

Zoroaster

The prophet Zarathustra, known to the Greeks as Zoroaster, lived about 1200 BCE, three hundred years before Karl Jaspers’ Axial Age, yet aspects of what he taught transformed Aryan beliefs in a way that anticipated the Axial prophets. His influence can still be seen in contemporary Judaism, Christianity and Islam more than 3,000 years after his estimated birth.

From the Gathas, the seventeen inspired hymns attributed to him, we know that Zoroaster was a priest steeped in the traditions of the Aryan faith, with its emphasis on order, justice and self-sacrifice. Like most of the more traditional, Avestan-speaking Aryans, he was deeply concerned by the upheaval and suffering brought about by a new warrior class.

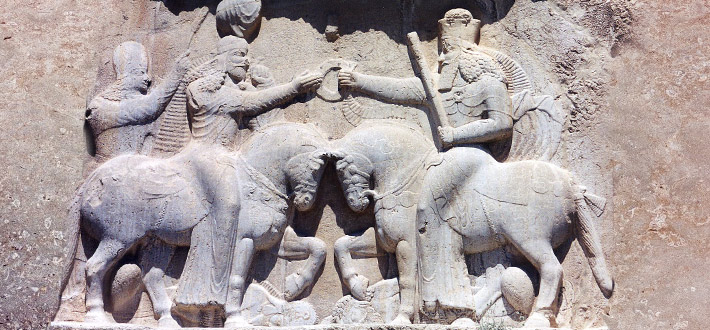

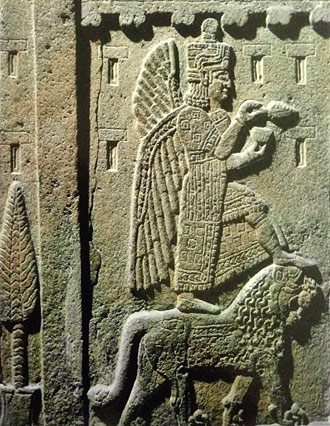

People were terrified. For them the spirit world paralleled the physical world. Thus, in addition to the tumult of their own lives, a simultaneous battle raged in the heavens between Indra, the god of war, and one of their most important gods, the peaceful Ahuras, who stood for justice, truth, harmony and respect for life. Above all the gods, these “warriors” honored Indra who rode a chariot upon the clouds of heaven, and they fought, robbed and raided in his name and with the force that his name inspired.

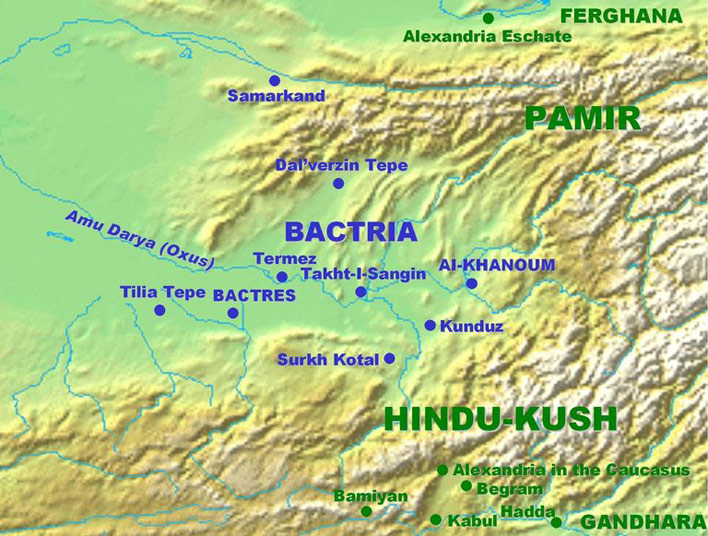

Though no one knows for sure, Zoroaster is said to have been born and lived in Bactria, located between the Hindu Kush mountain range and the Amu Darya river, a region that straddles modern-day Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. At the age of thirty he had a visionary experience in which he was led by a shining being into the presence of Ahura Mazda. The “lord of wisdom,” the supreme god of the ancient Iranians, told him to call his people to a holy war against the perpetration of terror, destruction and violence.

Zoroaster’s vision convinced him that Ahura Mazda was more than the lord of wisdom and justice; he was not only the benevolent Creator but also the one uncreated Supreme God. Ahura Mazda existed before everything. R.C. Zaehner explains this further in his classic book The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism, “Zoroaster raised the stature of Ahura Mazda, seeing him not merely ‘the greatest and best of gods’ but the sole creator and preserver of the universe, omnipotent and omniscient Lord … He is called the ‘father’ of the Holy Spirit and the Good Mind of Truth and Right-mindedness, but these entities are not brought into being by any crassly physical act of generation, they are thought into existence as eternal attributes of God himself.”

Zoroaster felt that all physical creation was thus a product of—and ran according to—a master plan, inherent to Ahura Mazda. Key to this is the concept of Rta asha (or aša), literally “truth.” Rta asha was evident in everything created: the motion of the planets and astral bodies, the progression of the seasons, and the pattern of the people’s daily life. Violations against the Rta asha were called Druj and were synonymous with violations against creation, and thus against Ahura Mazda.

Zoroaster’s revelation was that the purpose of humankind is to assist in maintaining Rta asha. But uniquely for a thinker of his time, he believed in individual responsibility and free will. A person could choose or not choose to assist Rta asha through his every deed and action, his every choice and thought. According to the Gathas, it is only through “good thoughts, good words, good deeds” that Rta asha can be maintained. Ahura Mazda “has left to men’s wills” (Yasna 45.9) the choice between doing good and doing evil (bad thoughts, bad words and bad deeds).

The fight against Druj would not resolve in the people’s lifetime, according to Zarathustra, but Ahura Mazda would ultimately prevail. Then the universe will undergo a cosmic renovation. A savior-figure, a Saoshyant, born of a virgin, would bring about a final renovation of the world in which the dead will be revived. Druj ,or evil, will be dispelled from the earth and from the heavens. Rta asha, or good, will triumph. Humanity will become immortal spirits. Everyone will speak a single language, belong to a single nation without borders and will share a single purpose and goal, the perpetual exaltation of Ahura Mazda.

Zoroaster’s teaching was not well received by his community. People found it too demanding and some were shocked that his message included everyone, including women and peasants. However, by the end of the second millennium BCE, the Aryan migrants had taken Zoroastrianism into eastern Iran where it eventually became established as the state religion of the Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great in the sixth century BCE, and it remained so until the rise of Islam in the seventh century CE.

Zoroaster’s life and words influenced the world’s great monotheistic religions. He was, says Mary Boyce in Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, “the first to teach the doctrine of individual judgment, Heaven and Hell, the future resurrection of the body, the general Last Judgment and life everlasting for the reunited soul and body.” She points out that “These doctrines were to become familiar articles of faith to much of mankind through borrowings by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam; yet it is in Zoroastrianism itself that they have the fullest logical coherence.”

The attribution of “Supreme Creator” was an entirely new concept for Aryans, as far as we know. Zoroaster’s concept of a purpose and a goal to life, the notion of progress, reform and advancement, changed the fundamental concept of time from a cyclical one held by ancient peoples to the linear concept we have to this day. As far as we know, he was the first to understand that one’s choices about good and evil determine one’s life. In his ethical vision, in his idea of individual responsibility and in his concept of a free will, we see a prophet who heralded those of the approaching Axial age.