Neolithic Era:

Pyramids: Stairways to the Gods

Djoser’s step pyramid at Saqqara, Egypt (Charles J. Sharp). Wikimedia Commons

Pyramid-shaped structures are yet another example of how human beings expressed their psychological understanding of our place in the universe as three-tiered. Ancient examples are found on at least three continents: in Asia, Africa and the Americas. Of different constructions and functions, they all served to connect people to the heavens. And the human being’s heaven, the home of the god(s), is always above.

The pyramid is the simplest structure that humans could build that would function as a step to the heavens. Without modern reinforcement inside a tower or similar structure, the only way to build higher is to have the largest part at the bottom, and succeeding levels smaller, so the structure doesn’t topple.

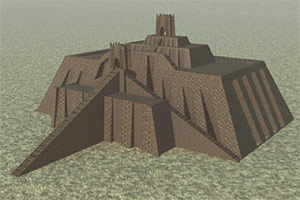

Ziggurats, the stepped pyramid-like structures common to Sumerians, Babylonians and Assyrians, were temples whose function was to house the god and ensure that he/she remained close to them. Atop each ziggurat was a sacred shrine in which the god actually was present. Ziggurats date from the end of the third millennium BCE, a little earlier than the first Egyptian examples, until around the sixth century BCE.

Their designs evolved from simple bases upon which a shrine sat to receding tiers up to seven levels tall. They were built of sunbaked mud bricks upon a rectangular, oval, or square platform, with the shrine at the summit. Ziggurats could be massive: the construction of the Ziggurat of Ur measured 210 feet in length, 150 feet in width and possibly over 100 feet in height. The later Marduk Ziggurat of Babylon, or Etemenanki, “The Foundation of Heaven and Earth,” measured 298.48 feet (91 meters) in height with a square base also of 298.48 feet on each side. Exteriors of these temples were often faced with fired bricks glazed with different colors that may have had astrological significance.

During Shugli’s 48-year reign, the city of Ur grew to be the capital of a state controlling much of Mesopotamia. The royal tombs of Ur contained 74 carefully arranged skeletons all entombed at the same time, which implies that monarchs took their staff along with them to the next life.

Egyptian pyramids were even bigger. The earliest among the Egyptian pyramids is the stepped Pyramid of Djoser (constructed c. 2630–2611 BCE) during the third dynasty. It was 203 feet high and 411 feet at the base. Egyptian pyramids had a different function. For the Egyptians the afterlife was of paramount importance, so pharaohs had extravagant tombs built during their lives, which would assist their passage into the heavens above after their death. The stepped Pyramid of Djoser, named after the pharaoh, was designed to serve as a gigantic stairway by which his soul could ascend to the heavens.

Some scholars, such as the English Egyptologist I.E.S. Edwards, conjecture that the idea of the pyramid shape came from the image of the sun’s rays coming through clouds; others that it referred to the Egyptian Nu the primal island of creation, and still others that it was influenced by the shape of meteorites, that tend to appear conical in shape when they land on the earth intact. Recent evidence of roughly pyramid-shaped iron meteorites have been found in the US and elsewhere in the world: in Missouri, Colorado, Arizona, Nebraska and Alabama, São Paulo State Brazil, Omolon in Beringia, and Zaklodzie in southeast Poland.

Egyptian pyramids were often composed of local limestone, with finer quality limestone on the outer layer giving them a white sheen that could be seen from miles away. The capstone was usually made of granite, basalt, or another very hard stone and could be plated with gold, silver or electrum, an alloy of gold and silver, which would also be highly reflective in the bright sun.

Recent findings of equally ancient pyramid structures have been discovered in Brazil to the extent that archaeologists estimate that around a thousand pyramids were once built on the Atlantic coast in the south. The oldest so far found dates from 3000 BCE.

These pyramids were built exclusively of seashells. Because of this they were until very recently mistaken for domestic garbage from early settlements. Like the Egyptian, these pyramid structures also contain hundreds of human burials, complete with spectacular grave goods—including stone plaques, shell breast-plates and beautifully made stone birds, fish, whales and other animals.

One of the largest surviving examples—near the town of Jaguaruna in the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina—still covers 25 acres and stands 100 feet high, which archeologists think is possibly up to 65 feet less than its original height. Some of these pyramids—like their later Mexican counterparts—had structures on top of them, although the Brazilian examples are up to 3,000 years older than the ones in Central America.

“Our new research shows that Brazil’s prehistoric Indians 5,000 years ago were more sophisticated than we had thought and were capable of producing truly monumental structures,” said Professor Edna Morley, the director of the Instituto do Patrinionio Historico e Artistico National (National Heritage Institute) in Santa Catarina where most of the Brazilian pyramids have been discovered.

Caral is an ancient ceremonial center in the Supe Valley in Peru, some 200 km north of Lima, dated to about 2700 BCE. The largest of the Caral pyramids, the Greater Pyramid, is 358 feet wide and 90 feet high. Caral spawns 19 other pyramid complexes scattered across the 35-square-mile area of the site.