How Do We Maintain a Stable World?

Wassily Kandinsky, Animated Stability

The achievement of the human mind is to create a sense of stability in a world where there is constant change. We evolved certain strategies to achieve this.

The content of this section, unless indicated, represents Robert Ornstein’s award-winning Psychology of Evolution Trilogy and Multimind. It is reproduced here by kind permission of the Estate of Robert Ornstein.

Keep It Simple

As adults, we experience our “world” as stable. We arise aware that we are in the room where we slept in the dark last night; that the streets outside are the same as they were, the town is the same, and we speak the same language. But it isn’t always so in a person’s life; the “world” of the young child is not so stable, nor is that of the teenager. Stability is something that we develop as we age.

There’s a lot of work behind the scenes to make this happen, and it comes at great cost: We have to simplify, overgeneralize, ignore, predict, and make assumptions. It’s a constant that much of our experience is edited out scene by scene, moment by moment, feature by feature. Remember: You haven’t seen your nose lately, nor are you aware of what happens, thousands of times per day, when you blink and the world doesn’t disappear into a black nothingness.

Our mental state actually changes radically during the day, each day — for example, when we dream or daydream, or in the hypnagogic state between sleep and wakefulness. We all experience these kinds of extraordinary visions in our dreams. But because dreams happen nightly, by day we mostly disregard them, they’re ordinary. The experience is so common that the resulting revisions and “program changes” are unremarked.

Our experience of the world assembles in a fleeting instant, with no time for thinking but just enough for producing a best guess of the world. To act quickly we assume a lot about the world we perceive. If I tell you that you are in a room, you immediately assume the room has four walls, a floor, a ceiling, and probably furniture. On entering a room we do not inspect it to determine whether the walls are at right angles, or that the room is still there when we leave it. If we constantly inspected everything in our environment, there would be no time to do anything.

We bet that the room is rectangular because almost all the rooms in our experience have been rectangular. But if the room is in fact not rectangular, our bet causes us to see objects or people in the room in a very strange way. Take a look at what happens in a room that is not rectangular (Ames Illusion).

Humans live in all types of environments in the world and have lived in many cultures. As we discussed in the introduction to this website, much of our perceptual experience is learned. For instance, pygmies of the Congo dwell primarily in dense forest and thus rarely see across large distances. As a result, they do not develop as strong a concept of size constancy as we do. Colin Turnbull, an anthropologist who studied pygmies, once took his pygmy guide on a trip out of the forest. As they were crossing a wide plain, they saw a herd of buffalo in the distance.

Kenge looked over the plain and down to a herd of buffalo some miles away. He asked me what kind of insects they were, and I told him buffalo, twice as big as the forest buffalo known to him. He laughed loudly and told me not to tell him such stupid stories…. We got into the car and drove down to where the animals were grazing. He watched them getting larger and larger, and though he was as courageous as any pygmy, he moved over and sat close to me and muttered that it was witchcraft…. When he realized they were real buffalo he was no longer afraid, but what puzzled him was why they had been so small, and whether they had really been small and suddenly grown larger or whether it had been some kind of trickery.

Comparisons and Categories

It is very difficult for us to judge anything absolutely, as we are wired to measure things only by comparison. Things are not heavy but are heavier than we expect or were previously experiencing — brighter, richer, more intelligent. We adapt to temperatures, to a level of income or net worth, to comfort, to taste; and we judge based on our assumed level of adaptation.

As we mature, we attempt to make more and more consistent sense out of the mass of information arriving at our receptors. We develop stereotyped systems, or categories, for sorting input. The set of categories we develop is limited, much more limited than the input. Simple categories may be “straight,” or “red.” More complex ones may be “English,” or “in front of.”

Previous experience with objects and events strengthens personal category systems. In social situations, the categories may be personality traits. If we categorize a person as, say, aggressive, we then consistently tend to sort all that individual’s actions in terms of this category. In the same way, we expect cars to make a certain noise, traffic lights to be a certain color, food to smell a certain way, and certain people to say certain things. In fact, as we will see later, your brain is constantly guessing or predicting what you will experience based on your past experiences and your culture.

What we actually experience is the category which is evoked by a particular stimulus, not the occurrence in the external world.

Language shapes how we categorize the world and influences our thinking. A particular language makes certain ideas more available than others. There are words in all languages that are not translatable into other languages. Gemütlichkeit, gestalt and zeitgeist are German words that have no direct English equivalents. The Eskimo and the Arab need hundreds of words for snow or camel because they encounter these daily and need fine distinctions for survival. Certain languages, like Hopi, have no words for past and future.

Since there are over 7,000 spoken languages around the world, there are at least 7000 cognitive worlds. Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky shows how our language can even change what color you see when you look out at the world.

Each language enables certain perceptions and thoughts, while excluding others. This fact underlies two essential aspects of our consciousness and experience. First, people in other cultures with different languages perceive the world differently. While this may make communication difficult, it also creates opportunities, for those open to it, to take advantage of different insights and ways of perceiving. And second, as we discuss in the section devoted to storytelling, it means that using language, materials, and patterns of thought from other cultures can change our ability to perceive and experience the world.

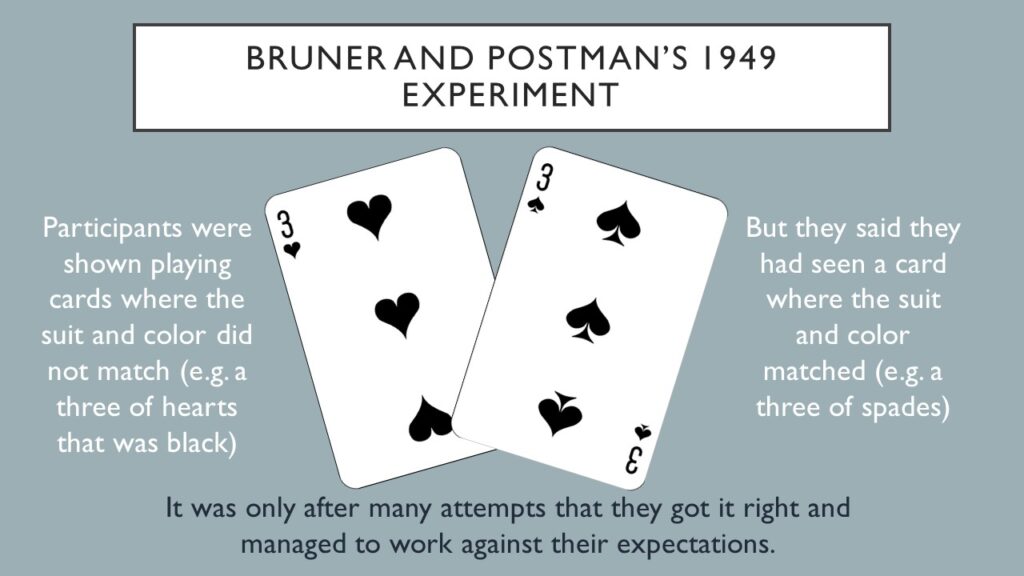

A classic trick-card experiment by Jerome Bruner and Leo Postman demonstrated the effects of our well-learned categories on the contents of awareness. Our past experience with playing cards evokes categories in which the colors and the forms of playing cards are supposed to fall. In this experiment some of the cards presented to the subjects were normal and some were altered, such as a black three and four of hearts and a red two and six of spades. Subjects had great difficulty in identifying the atypical cards when asked to count how many spades they saw. They weren’t able to “see” a spade if it was red instead of black.

The import of these and others of Bruner’s demonstrations is that at each moment we construct a model of the world, expect certain correspondences of objects, colors and forms to occur, and then experience our categories. We see what we expect to see, not necessarily what is there.

It’s hard to see what you don’t expect to see.

Experience and Expectation

The so-called “invisible gorilla” demonstration is now quite well known. In it the cognitive psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris revealed how people can focus so hard on something that they become blind to the unexpected, even when staring right at it. When one develops “inattentional blindness,” as this effect is called, it becomes easy to miss details when one is not looking out for them.

Simon noted that “A lot of people seem to take the message of our original gorilla study to be that people don’t pay enough attention to what is happening around them, and that by paying more attention and ‘expecting the unexpected,’ we will be able to notice anything important.”

The Monkey Business Illusion

Simon, in conversation with livescience.com concludes that “The new experiment shows that even when people know that they are doing a task in which an unexpected thing might happen, that doesn’t suddenly help them notice other unexpected things.”

“Once people find the first thing they’re looking for,” he continues “they often don’t notice other things. Our intuitions about what we will and won’t notice are often mistaken.”

Values and needs shape what we see, hear and feel

Another experiment compared the experiences of rich and poor children. When shown a certain coin, children from poor homes experienced it as larger than did the richer children, a finding that has been repeated in other cultures, such as in Hong Kong. In another study students in a class were asked to draw a picture of the teacher. The majority of the honor students drew the teacher slightly smaller than the students in the picture. But the pictures by less-than-average students depict the teacher as much taller than the students.

Psychologists Albert Hastorf and Hadley Cantril studied the influence of bias on perception at a Princeton-Dartmouth football game. During the game, Princeton’s star quarterback was injured. Afterward, Hastorf and Cantril interviewed two groups of fans and recorded their opinions of the game on a questionnaire. The Princeton fans said that Dartmouth had been unduly violent and aggressive toward their quarterback. The Dartmouth fans reported that the game was rough but fair. What a football game looks like depends on whether you are from Dartmouth or not — even when you don’t see the game live but as a movie:

When Princeton students looked at the movie of the game, they saw the Dartmouth team make over twice as many infractions as their own team made. And they saw the Dartmouth team make over twice as many infractions as were seen by Dartmouth students when they looked at the movie. When Princeton students judged these infractions as “flagrant” or “mild,” the ratio was about two “flagrant” to one “mild” on the Dartmouth team, and about one “flagrant” to three “mild” on the Princeton team….

When Dartmouth students looked at the movie of the game, they saw both teams make about the same number of infractions. And they saw their own team make only half the number of infractions the Princeton students saw them make. The ratio of “flagrant” to “mild” infractions was about one to one when Dartmouth students judged the Princeton team, and about one “flagrant” to two “mild” when Dartmouth students judged infractions made by their own team.

In this particular study, one of the most interesting examples of this phenomenon was a telegram sent to an officer of Dartmouth College by a member of a Dartmouth alumni group in the Midwest. He had viewed the film which had been shipped to his alumni group from Princeton. The alumnus, who couldn’t see the infractions he had heard publicized, sent the following message:

Preview of Princeton movies indicates considerable cutting of important part please wire explanation and possible air mail missing part before showing scheduled for January 25 we have splicing equipment.

The “same” sensory impingements emanating from the football field, transmitted through the visual mechanism to the brain, also obviously gave rise to different experiences in different people. The significances assumed by different happenings for different people depend in large part on the purposes people bring to the occasion and the assumptions they have of the purposes and probable behavior of other people involved.

The Authors Conclude:

It seems clear that the “game” actually was many different games and that each version of the events that transpired was just as “real” to a particular person as other versions were to other people.

Our own basic cognitive and perceptual mechanisms influence our perceptions of fairness or objectivity — we create bias from our individual experiences. Doing so has helped group survival for eons. Today, awareness of this unconscious tendency is relevant — if not crucial — in a wide range of situations, especially where mediation or negotiations take place.

Another example of how culture affects perception of reality is a 1985 study from Stanford University. Pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli students were shown the same news filmstrips pertaining to the massacre of Palestinian refugees by Christian Lebanese militia fighters in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. Although they were identical news clips, both sides found that the film was slanted in favor of the other side. Pro-Israeli students reported seeing more anti-Israel references and fewer favorable references to Israel in the news report, and pro-Palestinian students reported seeing more anti-Palestinian references and fewer favorable references to Palestine. Both sides said a neutral observer would have a more negative view of their side from viewing the clips, and that the media excused the other side where it blamed their side. Subjects differed along partisan lines on simple, objective criteria such as the number of references to a given subject.

The authors of the study, Vallone, Ross and Lepper, note that: greater knowledge of the crisis was associated with stronger perceptions of media bias.

They concluded that media bias appears to reflect more than self-serving attempts to secure preferential treatment. “Whether it is sports fans’ perceptions of referees, spouses’ perceptions of family-crisis counselors, or labor and management’s perceptions of government arbitrators, even the most impartial mediators are apt to face accusations of overt bias and hostile intent. Such accusation, our analysis suggests, may involve far more than unreasoning and unreasonable wishes for preferential treatment. Rather, they may reflect the operation of basic cognitive and perceptual mechanisms that must be understood and successfully combated if mediation or negotiation is to succeed.”

Our own basic cognitive and perceptual mechanisms influence our perceptions of fairness or objectivity — we create bias from our individual experiences. Doing so has helped group survival for eons. Today, awareness of this unconscious tendency is relevant — if not crucial — in a wide range of situations, especially where mediation or negotiations take place.

In brief, the data from such experiments indicates that there is no such thing as a game or an event existing out there in its own right which people merely “observe.” An event exists for each of us and is experienced by us only in so far as it has a personal significance. This confirms what we’ve already seen: Out of all the occurrences going on in the environment, we each select only those that have significance for our own survival.

In the series: Maintaining a Stable World

Related articles:

- An Ancient Brain in a Modern World

- Our Unconscious Minds

- The Multiple Nature of Our Mind

- Connecting with Others

- Morality’s Long Evolution

- Unconscious Associations

- The Brain’s Latent Capacities

- God 4.0

- Multimind: A New Way of Looking at Human Behavior

- Thinking Big

- Social

- The Righteous Mind

- New World New Mind

- Moral Tribes

- The Mountain People

- The Matter with Things

- Humanity on a Tightrope

- Beyond Culture

Further Reading

External Stories and Videos

How language shapes the way we think

Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky shows how our language can even change what color you see when you look out at the world.

Ted Talk