Our Unconscious Minds:

Is Our Reality Real?

The “reality” each organism lives inside—whether it is our own or that of ants, cows and, for all we know, grass—is a virtual one. Each organism has evolved a sensory system and a nervous system to select what it needs to get through the day in its neighborhood.

The content of this section, unless indicated, represents Robert Ornstein’s award-winning Psychology of Evolution Trilogy (God 4.0, The Evolution of Consciousness and The Psychology of Consciousness) and Multimind. It is reproduced here by kind permission of the Estate of Robert Ornstein.

If you are a plant, you don’t need to know much, really; if you are a frog, a few items reach your senses; a cat, more items; a bonobo, much more; and we humans, more still. All of these “small worlds,” though different, are not arbitrary; they are virtual adaptations of external reality that evolved long ago for the survival needs of each organism.

At almost each moment of each day we assume that our own personal consciousness is the world, that an outside objective reality is somehow received by us in its completeness. After all, we’ve eaten the same food as have all the other people at dinner this evening, we’ve watched the same football game. Most people never really see any issue here; for ordinary purposes the reality we experience in our everyday lives goes unchallenged.

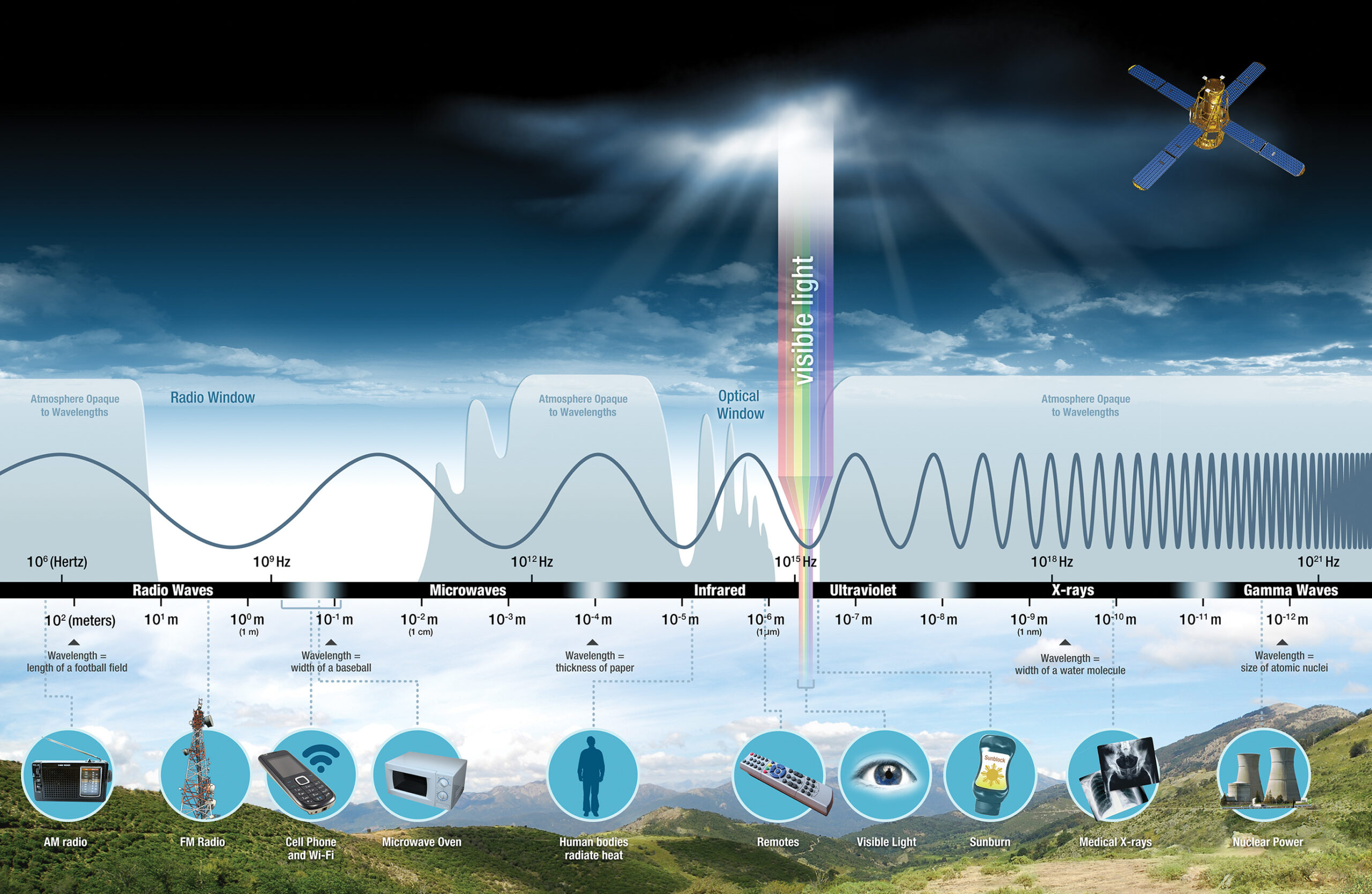

But think about it—there’s the enormous variety of physical energies that we contact at each moment of our lives. The air, or more properly, our atmospheric environment, contains and conveys to us energy in the electromagnetic band: visible light, X-rays, radio waves, infrared radiation. In addition, the air is mechanically vibrated, by vocal chords, drums, passing cars, the movement of our feet; this conveys energy that transforms into sound information. There is constant energy from the gravitational field; there is varying pressure in our own body; there is the movement of gaseous matter in the air; and there are hundreds more events out there. In addition, we generate our own internal stimuli—thoughts, internal organ sensations, muscular activity, pains, feelings, and more.

And all this occurs simultaneously, and it continues for as long as we are alive. Imagine being aware of it all, all the time! Immediately you will see that our personal consciousness can never, even at any one instant, represent or reflect all the external and internal worlds, but must consist of an extremely small fraction of the entire reality.

Our “everyday” mind works as a device for selecting just a few parts of the outside reality that are important for our survival. So, we don’t experience the world as it is, but as a “virtual reality”—a small, limited system that has evolved to keep us safe and ensure our survival.

Based on what we now know about the mind’s workings, we can safely say that our everyday experience is not, in fact, “reality.” Rather, our ordinary awareness is a “virtual reality”—we make it up—it’s a personal construction, something computed within our minds, not a full or accurate registration of what is outside.

Our “everyday” mind works as a device for selecting just a few parts of the outside reality that are important for our survival. So, we don’t experience the world as it is, but as a “virtual reality”—a small, limited system that has evolved to keep us safe and ensure our survival.

Our Brain Selects Our Experience

“…insofar as we are animals our business is at all costs to survive. To make biological survival possible, Mind at Large has to be funneled through the reducing valve of the brain and nervous system. What comes out at the other end is a measly trickle of the kind of consciousness which will help us to stay alive on the surface of this particular planet….” Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception

We normally consider that the senses are the windows to the world, that we see with our eyes and hear with our ears. But although such a view explains our situation, it is not biologically the case. A primary function of sensory systems is to discard information that is irrelevant to the organism.

In fact, human sensory systems serve mainly for data reduction. From the limited, tiny fraction of information and energy that passes through our senses, we are continuously making up a virtual reality inside our brain.

The entire spectrum of wavelengths ranges from those less than 1 billionth of a meter long, to those longer than 1,000 meters; yet we can see only that tiny portion between 400 and 700 billionths of a meter long.

While our eyes can transmit to the brain a vast display of colors, shapes and movements, it’s nothing compared with what is going on outside of us. Only a miniscule amount—as little as one-trillionth—of the outside ambient energy that strikes the eye gets passed through to the brain. The cells in the retina and in the occipital cortex translate this small sample as the experience of light, and they code its different wavelengths as colors. Sensing may be carried out with the help of our senses, but it actually takes place in the brain.

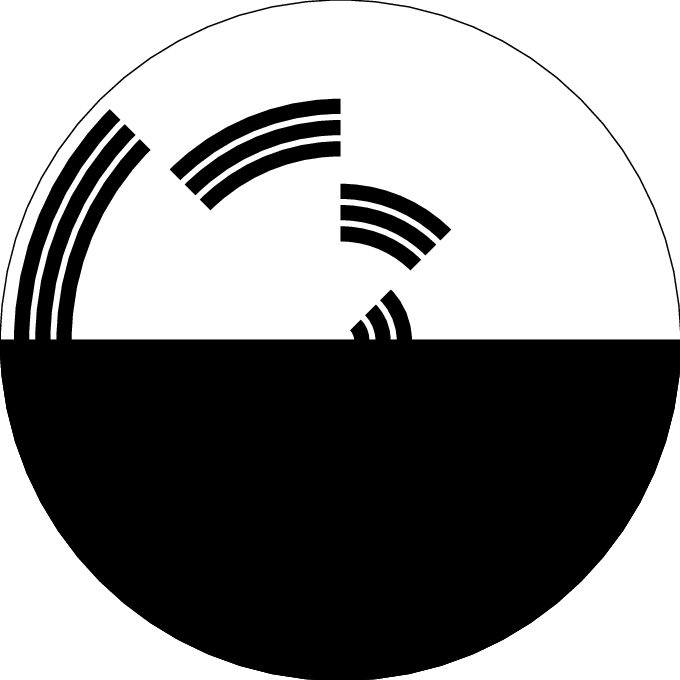

This video is of a “Benham’s disk,” a small circular diagram or spinning top that contains swaths of black and white. When you spin it, you see colors—usually red and green. There is no color in the disk itself, so what has happened? The black and white segments, at certain speeds, produce the same neural code that the eye sends to the brain for information about color.

We don’t (can’t) see color or the world directly. In the same manner, only a tiny fragment of the vibrations in the air that reach the ear are selected, coded and sent to the brain to finally become the experience of sound. The brain makes it all up and calls it “reality.” Although this may seem very, very strange, “strange” is the norm.

Since our reality evolved to ensure our survival, it of course has to have some correspondence with the external world, even on a miniscule basis. We are, after all, successful in being able to hold a coffee pot and pour coffee into a cup rather than over our hand, or to hear and respond to the cries of a hungry infant.

Because our brains are all organized in this way, we all perceive aspects of this world in the same way: We all see the sky, the moon, the ground and the sun, and many beliefs and myths are common to all of us.

Think of the mind, then, not as reflecting a complete reality, but operating as a device that selects a few parts of the outside reality that are important for our survival and safety, making contact with the world like an elaborate set of cat’s whiskers, physical antennae that touch parts of the world so that the cat can navigate.

There’s no real reason to consider these neuropsychological complexities and limitations when we’re all involved in the comings and goings of everyday life. That’s the point of the automatic filtering and highlighting. It keeps us unaware of all the work going on behind the scenes. We blink our eyes about nine or ten times each minute, all day, every day. This goes on constantly, except when we’re asleep. Last week, you blinked about 50,000 times; last year, several million times. And each time your vision is blocked, it goes completely black for a moment. But you’re not normally aware of this. What happens to those black moments—all of the millions of them during a lifetime? And think about your nose: If you look ahead carefully, you’ll see it’s that thing at the bottom of your field of vision—but why didn’t you see it before? And in a few moments, your nose will fade from view once again.

If we did not filter out all this extraneous information, we would be flooded by it and be so overwhelmed that we would be unable to attend to critical input that might determine our safety and survival. This “ignorance” is continuous and adaptive.

The Imaginal World—Making Sense Out of Chaos

How do we create and maintain everyday consciousness? Each of us selects and constructs a personal world in several ways. Our sense organs gather this miniscule amount of information from the outside world and further modify it by a mix of our memories, expectations, body movements and imagination.

We live in an Imaginal World, a virtual “Imaginarium” that’s rich with the stories provided by our culture and the stories we tell ourselves. All of it—everything in our mind, along with our sense of our family, our childhood, our past and future struggles, and all of our beliefs—inhabits our “Imaginarium,” defining how we understand and feel about the world.

Our imaginal beliefs and explanations have consequences, based as they are on our very limited perception and understanding of “reality.” We believe they are real and act accordingly. But each individual’s consciousness evolved for the primary purpose of ensuring that individual’s biological survival. Its major concern is for its own welfare. There is a “me first” system that takes priority.

It’s not a real world we experience but a set of signals, carefully evolved and curated from much of what’s outside. As T.S. Eliot said in Four Quartets, “You are the music while the music lasts.” This “illusion” or “small world” that we live inside is controlled and is limited by the mind’s barriers and filters, which evolved to ensure our survival.

Understanding the limitations of normal consciousness is important, perhaps even vital for our future. As the psychologist Robert Ornstein says, “Not knowing what is really going on [in the mind] has been the cause of conflict, wars and cultural divides, and now may even threaten humanity’s survival. This is all due to our failure to appreciate the limits of our senses, the selective nature of our everyday consciousness, and our potential for developing a higher, more comprehensive, more connected form of perception and consciousness.” (God 4.0 – On the Nature of Higher Consciousness and the Experience Called “God”)

Why is this important to know and understand? As Robert Ornstein states in his book God 4.0 – On the Nature of Higher Consciousness and the Experience Called “God”: “Not knowing what is really going on has been the cause of conflict, wars and cultural divides, and now may even threaten humanity’s survival. This is all due to our failure to appreciate the limits of our senses, the selective nature of our everyday consciousness, and our potential for developing a higher, more comprehensive, more connected form of perception and consciousness.”

Multimind: A New Way of Looking at Human Behavior

Robert E. Ornstein

This provocative book challenges the most-popularly held conceptions of who we are. In it, psychologist and renowned brain expert Robert Ornstein (1942 – 2018) shows that, contrary to popular and deep-rooted belief, the human mind is not one unified entity but, rather, is multiple in nature and is designed to carry out various programs at the same time.

The Matter with Things

Iain McGilchrist

In his masterly two-volume exploration of our brain hemispheres, Iain McGilchrist argues that in order to understand ourselves, the world and the universe, we need a combination of the right and left hemispheres working in tandem, but with the right brain leading the way.

Beyond Culture:

Edward T. Hall and Our Hidden Culture

Report by John Zada

Edward T. Hall, after spending his early adulthood working and travelling among non-Anglophones, both in the United States and in other parts of the world, became cognizant and fascinated in the deeper layers of culture that he claimed lie buried beneath those more obvious forms.

In the series: Our Mind in the Modern World

- An Ancient Brain in a Modern World

- Maintaining a Stable World

- The Multiple Nature of Our Mind

- Connecting with Others

- Morality’s Long Evolution

- Unconscious Associations

- The Brain’s Latent Capacities

- God 4.0

- Multimind: A New Way of Looking at Human Behavior

- Thinking Big

- Social

- The WEIRDest People in the World

- The Righteous Mind

- New World New Mind

- Moral Tribes

- The Mountain People

- The Matter with Things

- Humanity on a Tightrope

- Fluke by Brian Klaas

- Beyond Culture

- Think Again