The Marketplace of Ideas

Our traditional social networks, the ones we have belonged to since time immemorial, have always been our most important sources of information. But today, the information we get from our online social networks, unlike those of the past, are skewed by digital echo chambers.

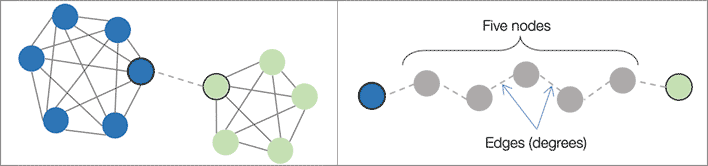

Networks exist at every size and level of life on earth. The most staggeringly complex networks are still the biological ecosystems—and the human brain. Humans live within multiple interwoven social networks including family, village, tribal, business, national, and international: and that’s before we add the digital networks to the picture. There are a number of network concepts and terms, which are better described in Wikipedia. But clusters and weak ties have a major relevance to the impact of Facebook. Network clustering occurs when a group of nodes (people, in this case) are closely interconnected, where each node has a relationship with all or most of the other nodes in the cluster. Most people belong to multiple network clusters. Everyone in a family or close friend network knows each other. Acquaintances are examples of weak ties in which we know someone but do not know anyone else in their network. Weak ties are a vital aspect of networks. It is through weak ties that viral ideas—and viruses—spread widely through the human community. You are more likely to learn something new from a weak tie than you are from those in your close network of friends and family. For example, people looking for jobs tend to be helped better by acquaintances than by close friends. Weak ties are essential for society to thrive. A lack of weak ties can perpetuate poverty and lack of opportunity within a community that has been cut off from the wider society due to ethnic or religious discrimination.

In his book, The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, from the Freemasons to Facebook, Niall Ferguson summarizes the research that supports the popular notion that everyone on earth is separated by only six degrees of separation. That is, there is an average of five acquaintances between you and everyone else on earth.

Users on the Facebook global network now have only 3.57 degrees of separation. This makes it possible for information of any kind to travel rapidly. However, the Facebook trending and curation algorithms ensure that you only see information that you are interested in. This creates a paradoxical effect. You can receive memes, news, and misinformation from across the globe in a matter of only hours or days, but it will only be the kind of information you want to see. The Facebook friend suggestion algorithms encourage dense clustering, which likely leads to greater homophily than what you would find in real life. The Facebook algorithms favour posts from friends you have shown an interest in previously over those that you have skimmed over. So even if your Facebook network is varied—you are also friends with people unlike you—you will still tend to see more posts from people who have similar attitudes to you. This means that even family and close friends with whom you are connected, both online and in real life may receive their information and news from radically different sources. This creates a filter bubble effect in which the same news stories are understood in entirely conflicting ways.

The Marketplace of Ideas

Historically, whenever a new communication tool enhances our ability to network big changes occur. It took decades for societies to adapt to the changes wrought by the printing press.

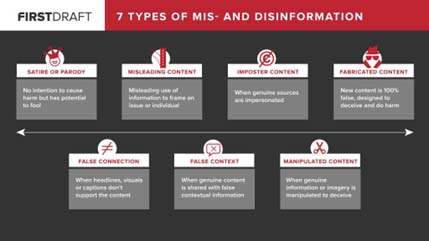

Prior to Web 2.0 our sources of information and knowledge were selected and presented by people who acted as gatekeepers. These were the newsroom and magazine editors, the universities, scientific journals, and textbook publishers who decided what the public should know. They provided the context by which major events and historical facts should be interpreted and understood. “All the news that’s fit to print” as it still says on the cover of the New York Times. This was by no means a perfect model for an information ecosystem. Its main problem was the amount of influence that the corporate owners had on what we were allowed to know. This was followed by the focus on exciting events over much more serious but gradual and ongoing trends. But gatekeeping also provided essential guardrails. A combination of laws and self-imposed norms prevented the media from publishing deliberate falsehoods.

Traditional media followed the hierarchical form of governance and information flow. The universities and publishers print and distribute textbooks to the schools and students. News flows from major newspapers and broadcasters out to local stations and newspapers. The internet has changed this relationship.

Mumbai

This first became evident in 2008. In their book, LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media, Peter Singer and Emerson Brookings recount the Mumbai terrorist attacks that occurred in that year. Had they occurred even three years earlier than they did, the traditional media of print and television would have taken days to report on what had happened, and weeks to fully piece together the events into a complete picture for the TV and Newspaper audiences. But by that point digital technology and social media platforms had brought remarkable powers to ordinary citizens. Minutes after the attacks began Mumbai residents were tweeting where they were occurring. Within hours reports and pictures of the attacks spread across the social media platforms. It was these amateur photos that professional journalists used to fill the papers and TV screens the next day. Now, it is very common to see news organization contacting citizens for permission to use their phone or dashcam videos, after they have posted them on twitter.

The Anxious Generation

How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness

An essential investigation into the collapse of youth mental health—and a plan for a healthier, freer childhood.

By Jonathan Haidt (2024)

In the series: Social Networks

Further Reading »

Websites:

Data & Society

Data & Society studies the social implications of data-centric technologies & automation. It has a wealth of information and articles on social media and other important topics of the digital age.

Stanford Internet Observatory

The Stanford Internet Observatory is a cross-disciplinary program of research, teaching and policy engagement for the study of abuse in current information technologies, with a focus on social media.

Profiles:

Sinan Aral

Sinan Aral is the David Austin Professor of Management, IT, Marketing and Data Science at MIT, Director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy (IDE) and a founding partner at Manifest Capital. He has done extensive research on the social and economic impacts of the digital economy, artificial intelligence, machine learning, natural language processing, social technologies like digital social networks.

Renée DirResta

Renée DiResta is the technical research manager at Stanford Internet Observatory, a cross-disciplinary program of research, teaching and policy engagement for the study of abuse in current information technologies. Renee investigates the spread of malign narratives across social networks and assists policymakers in devising responses to the problem. Renee has studied influence operations and computational propaganda in the context of pseudoscience conspiracies, terrorist activity, and state-sponsored information warfare, and has advised Congress, the State Department, and other academic, civil society, and business organizations on the topic. At the behest of SSCI, she led one of the two research teams that produced comprehensive assessments of the Internet Research Agency’s and GRU’s influence operations targeting the U.S. from 2014-2018.

YouTube talks:

The Internet’s Original Sin

Renee DiResta walks shows how the business models of the internet companies led to platforms that were designed for propaganda

Articles:

Computational Propaganda

“Computational Propaganda: If You Make It Trend, You Make It True”

The Yale Review

Claire Wardle

Dr. Claire Wardle is the co-founder and leader of First Draft, the world’s foremost non-profit focused on research and practice to address mis- and disinformation.

Zeynep Tufekci

Zeynep is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill at the School of Information and Library Science, a contributing opinion writer at the New York Times, and a faculty associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. Her first book, Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest provided a firsthand account of modern protest fueled by social movements on the internet.

She writes regularly for the The New York Times and The New Yorker

TED Talk:

WATCH: We’re building a dystopia just to make people click on ads

External Stories and Videos

Watch: Renée DiResta: How to Beat Bad Information

Stanford University School of Engineering

Renée DiResta is research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, a multi-disciplinary center that focuses on abuses of information technology, particularly social media. She’s an expert in the role technology platforms and their “curatorial” algorithms play in the rise and spread of misinformation and disinformation.