Homo Ergaster and Erectus: Down from the Trees

Living entirely on the ground and the first to venture out of Africa, Homo ergaster/erectus may have been first to live in bands of hunter-gatherers and use fire to cook food.

Homo erectus or “upright/standing man” evolved from H. habilis. H. erectus became bipedal at least 3 to 4 million years ago and first moved out of Africa about 1.8 million years ago.

H. erectus is what biologists call a chronospecies, a species that changes through time. Homo ergaster is the name given to its earlier phase, which lived mainly in Africa; the later Homo erectus lived mostly in Eurasia.

Homo erectus stood upright and had a larger brain than several of its forebears, averaging between 780 to 1225 cc, considerably larger than H. habilis, the first of the genus Homo. Our modern human brain is about 1500 cc. The adult H. erectus was roughly 5 feet tall, with heavy, dense big bones, a large nose and a long, flat skull.

H. erectus was the first early human to venture out of Africa and spread throughout the Old World. Its body was well adapted for running, with long legs and long Achilles tendons. While earlier hominids spent considerable time in trees as well as on the ground, H. erectus appears to have been fully terrestrial. It traveled for long distances, along the African and Eurasian coasts. The ice age had caused sea levels to drop, which may well have made it easy for groups to obtain food, as they moved along the coasts. Shellfish, and other aquatic food sources, rich in omega-3, iron and other nutrients beneficial to brain development would have been plentiful. H. erectus reached as far as China in the East and Northern Europe in the West.

A 2004 study found that a variant of the MC1R gene, which is known to be important for darker skin color, was already present 1.2 million years ago.

This adaptation suggests that by this time our ancestors were well on the way to becoming hairless. The hair on our head remained, since it helped to combat overheating, by shielding the brain from the sun. The loss of body hair is associated with our propensity to sweat, which is an ideal way to regulate body temperature. This was important because, although being upright meant that our bodies were exposed to less direct sunlight, we needed to run long distances in order to hunt large game animals. Losing our body hair helped us lose heat by sweating, helping to enable a diet rich in the proteins needed to fuel our growing brains, which, in turn, set the stage for more and more complex tasks, such as symbolic thought and language.

H. erectus were most likely the first to live in bands organized as hunter-gatherers, which would mean that they were able to coordinate their hunting behavior and most likely had some capacity for language. They cared for their injured relatives; and, as far back as 1.7 million years ago, created the most successful tool ever invented by any hominid: the bifacial hand axe. Known as Acheulean, these stone tools are evidence of our longest-running industry, lasting well over a million years, with examples found from southern Africa to northern Europe and from western Europe to the Indian sub-continent.

Recent findings spanning 1.2 million years from the Olorgesailie Basin in the Rift Valley confirm that about 900,000 years ago erectus used big Acheulean hand axes and scrapers to butcher meat. 100,000 years later as the climate began fluctuating more intensely from wet to dry, the environment became more arid and grassy. With the possibility of freer movement came the creation of smaller basalt Acheulean tools that could be carried for long distances. The last hand ax at this site dates to 499,000 years ago, before a gap caused by ancient erosion stripped away evidence until about 320,000 years ago. By this time the Acheulean tools were gone, and tools with more precise blades and points that would have been hafted onto spears were plentiful. Many of the tools were made from a black volcanic rock called obsidian, which may well have been brought to the site and processed there from sources up to 100 kilometers away. But “these are straight-line distances that, in some cases, go over the top of a mountain,” says Alison Brooks from George Washington University. So they may well indicate the earliest examples of long-distance trade, pushing this date by 80,000 to 100,000 years.

In a 400,000-year-old site in Jaljulia, central Israel, archeologists also found flint tools that were produced using the more complex Levallois technique. Rather than simply hammering until the required shape is achieved, this technique required the maker to accurately conceive the tool within the selected flint core before he began to create it. It indicates that H. erectus had more advanced cognitive abilities than was previously thought.

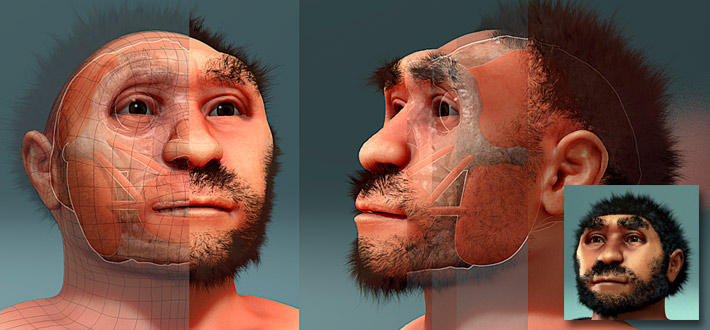

An article in the March/April 2018 issue of Archaeology, “Imaging the Past,” shows how multi-disciplinary approaches can help us understand more about our evolution:

Erectus’ Archeulean tools were deliberately shaped from raw pieces of flint by applying pressure to the stone. These toolmakers had to have an idea of the overall shape they wanted before they started. A kind of planning, learning and control that likely contributed to the doubling of our human brain size.

According to archaeologist and flintknapper Alex Woods from Colorado State University, “You can see a tool, even one that’s millions of years old, with four or five mistakes in a row that were part of a thought process. It’s the only time in archaeology where you can take a quantum leap back in time into the mind of a person … it’s problem-solving, fossilized.”

Evolutionary anthropologist Dietrich Stout from Emory University trained participants to knap flint. It was anything but easy: his volunteers needed an average of 167 hours of practice to produce passable Acheulean hand axes. They were then subjected to MRI scans while they watched videos of someone else making the tools, while Stout and his team noted the precise areas in the brain that were particularly active during Acheulean toolmaking. One interesting example was activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus, a region that is known to help with impulse control and performing multiple tasks.

Stout’s experiments showed that the more a person practiced knapping flint, the more brain matter built up in the regions responsible—providing powerful evidence that toolmaking helped shape the modern human brain. But it turns out that this did not mean that erectus had language. Further experiments showed that in the absence of verbal instruction the brain relied on a combination of working memory and motor-control to make these tools. Like playing the piano, you can make a hand ax without language … by coordinating your hands while keeping in mind all of these sub-goals.

A large collection of shells, very similar to each other and dated about 500,000 years old, appear to be H. erectus’ shell tools. Some of them have geometric engravings which are thought to have been made by H. erectus. The earliest portable representations of the human figure were created by H. erectus. A small quartzite figurine from Morocco, known as Tan-Tan, dates from between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago. It is at least 99 percent created by nature and may well have been safeguarded by our hominid ancestors, who, because of their emerging self-consciousness, were able to recognize that it resembled the female form and hence was most likely infused with meaning that was of a magical or religious significance. Though largely natural, a tiny piece of volcanic rock known as the Venus of Berekhat Ram, was found in Israel’s Golan Heights. It was deliberately modified somewhere between 280,000 and 700,000 years ago to represent the female form, probably carved by Homo erectus. These examples predate the earliest known engravings found at the Blombos Caves in South Africa.

It is thought that H. erectus were the first to harness fire and cook food. Richard Wrangham, Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human, feels this may well have occurred with the earlier Homo habilis and gave rise to H. erectus. He bases his theory on its larger brain and body, smaller gut, jaws and teeth and weaker jaw muscles—changes consistent with a more tender and energetically rich diet of cooked food.

Evidence from the erectus settlement studied at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov in Israel, for example, suggests not only that erectus controlled fire but that their settlements were planned. One area was used for plant-food processing, another for animal-material processing, and yet another for communal life.

H. erectus spread as far as China and Java. During this time, they shared the planet with other hominids: australopithecines and with two species of Paranthropus all of whom were tool-using, upright-walking, big-brained hominids.

Results from excavations at Kalinga in the Cagayan Valley of northern Luzon in the Philippines reveal that early hominins, (Homo erectus/ergaster) reached there more than 770,000 years ago. Retrieved from a clay bed, findings dated between 777 and 631 thousand years ago include 57 tools, a disarticulated skeleton of a now extinct species of rhinoceros bearing marks of having been struck by early humans, and fossil remains of several other extinct species. Similar sites with evidence of butchery marks are known from Choukoutien in China and in Ngebung in the Sangiran Dome of Java, Indonesia.

Before this Kalinga discovery the only known early human remains from the Philippines was a foot bone found in the Callao cave on the island of Luzon which was only 67,000 years old. It appears to have come from an individual who had some form of dwarfism, similar to the ‘hobbits’ (with a body size of about 3.2 feet), in Flores Island, (i.e., Homo floresiensis).

The distance between the Luzon and Flores islands is about 1700 miles. So the questions are where did they come from—north or west—and how did they travel? One possibility is sea crossing. Sea travel is the only way to explain the island settlements of Wallacea (Indonesia), Crete and, in the Arabian Sea, Socotra. To reach any of these island sites erectus had to cross the open ocean. Several researchers have suggested that Homo erectus was capable of building boats and traveling over the sea–an activity that geologist Casey Luskin asserts “would have required very high intelligence.”

Other scholars disagree, suggesting that these journeys were more likely accomplished using natural rafts of floating mangroves which are occasionally broken up by typhoons.

H. erectus lived nine times as long as our own species, and we don’t know why they eventually became extinct—they were still in China about 300,000–140,000 years ago.

Homo erectus began moving out of Africa about 2 million years ago and quickly populated Africa, Asia, and Europe. It’s hypothesized that the beginning of the ice ages about 950,000 years ago split the Homo erectus populations and contributed to their divergent evolution before they died out some 150,000 years ago.

Another hypothesis is that Homo erectus reached the Near East about 125 KYA and from there they moved across Asia and into Europe around 43 KYA in one direction, and east to South Asia, reaching Australia around 40 KYA in the other direction. East Asia was reached by 30 KYA.

The Gap

The Science of What Separates Us from Other Animals

Thomas Suddendorf

A leading research psychologist concludes that our abilities surpass those of animals because our minds evolved two overarching qualities.

Before the Dawn

Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors

Nicholas Wade

New York Times science writer explores humanity’s origins as revealed by the latest genetic science.

In the series: Our Hominid Predecessors

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

A Cultural Leap at the Dawn of Humanity

Ed Yong, The Atlantic

New finds from Kenya suggest that humans used long-distance trade networks, sophisticated tools, and symbolic pigments right from the dawn of our species.

Prehistoric ‘Picnic Spot” from Half a Million Years Ago Found in Israel

Ariel David, Haaretz

Trove of advanced flint tools indicates hominids developed modern thought patterns well before they physically evolved into modern humans.

1.5 Million-Year-Old Footprints Reveal Human Ancestors Walked Like Us

Megan Gannon, Live Science

In 2009, paleontologists discovered fossilized tracks in Kenya attributed to Homo erectus suggesting similarities to modern human feet. Now, researchers think there were so many similarities: because Homo erectus may have walked like we do today.

Zigzags on a Shell from Java Are the Oldest Human Engravings

Helen Thompson, Smithsonian.com

Oldest human geometric engraving, made by Erectus on shell tools, predates other examples by at least 300,000 years.