Featured Book

The Anxious Generation

How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness

By Jonathan Haidt (2024)

Report by Kathleen Mazor

Contributing Writer

“It matters what we expose ourselves to…we need to take back control of our inputs.”

– Jonathan Haidt

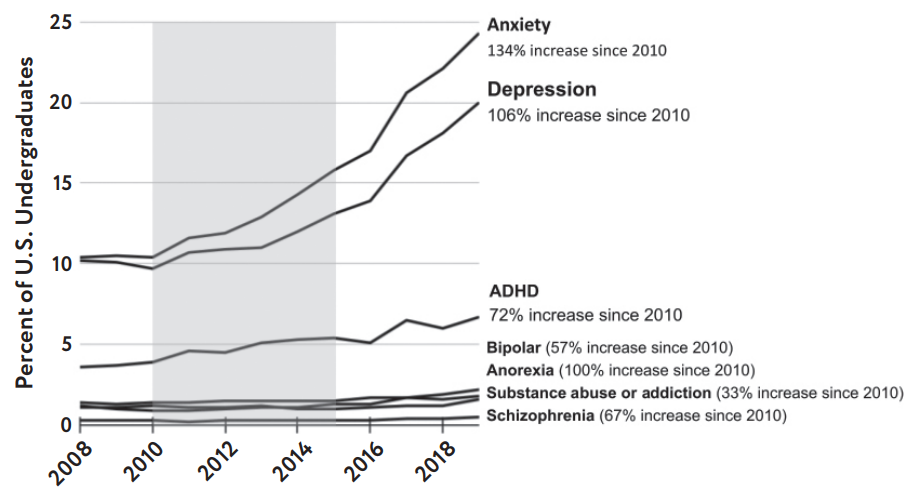

In The Anxious Generation, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt focuses on the alarming rise in teen mental illness that has swept across many countries in recent years, specifically affecting Gen Z (those born in 1995 and later). He says childhood was “rewired” between about 2010 and 2015, resulting in a mental health crisis that shows no sign of abatement. Citing evidence from numerous national and international studies and including important informational graphs documenting increases in anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicide, he contends that these trends are a direct result of two changes which led to the “Great Rewiring” of childhood: 1) a rise in parental fearfulness and overprotection since the 1990s, limiting free play; and 2) the widespread availability of smartphones, which launched a transition to a “phone-based childhood.”

Unsupervised, real-world play is critically important for all young mammals, and, given the complexities of our cultures, we humans are no exception. Studies show that experience, not information, is key to our emotional development. Haidt cites the work of Peter Gray, a developmental psychologist and leading play researcher, who notes that “play requires suppression of the drive to dominate and enables the formation of long-lasting cooperative bonds.” Children learn such social skills during free play – they learn to take turns, to negotiate, to resolve conflicts and more. Social bonds are created and strengthened through synchronous free play. It is widely known that children learn new languages much more readily than adults; perhaps less well-known is the fact that there are also crucial periods for learning social skills, including a sensitive period for learning culture, from about age 9 to 15. Social media hijacks social learning during this time – leveraging two “built in” human biases that affect learning: conformist bias, the tendency to go with the crowd, and prestige bias, the propensity to mimic the most accomplished (e.g., most popular). While these biases certainly influence adolescents (and adults) in the real world as well, social media exaggerates and amplifies these biases in ways particularly harmful to development during this sensitive period.

Free play confers benefits in other realms beyond the social realm. Children benefit from play that offers physical challenges and risks. By taking risks, children experience and learn from the consequences of small mistakes. Anticipating parental concerns about injury, Haidt notes that unsupervised, risky, outdoor play has been found to result in less physical harm than adult-supervised sports. He writes that “human childhood evolved in the real world, and children’s minds are ‘expecting’ the challenges of the real world.”

Many students nowadays believe that “one should be safe not just from car accidents and sexual assault but from people who disagree with you.”

Haidt describes two modes of interacting with the world. Discover mode (behavioral activation) comes into play when we recognize opportunities. Defend mode (behavioral inhibition) surfaces when we detect a threat. Haidt asserts that people tend to develop a “default setting,” with one of these modes predominant in how they interact with the world. He contends that defend mode has become the norm for Gen Z, due to the absence of free play and risk-taking. This is particularly worrisome because children are inherently “antifragile,” meaning that they need challenges during their development. Haidt uses the analogy of trees which need wind for normal growth, as wind strengthens their root systems and results in stronger wood. Similarly, children need freedom and the opportunity to take risks in the real world. Haidt argues that parents have become increasingly protective, restrictive and even paranoid since the 1990s, with the result that children are given less responsibility, and fewer opportunities to take risks. The net impact of this “safetyism” (where a concern for safety trumps all other considerations) in the real world has been negative, limiting children’s learning about risk, conflict, and autonomy. According to Haidt, overprotection encourages children to stay in defend mode, afraid to leave “home base.” He argues that a play-based childhood in the real world is fundamental and necessary to healthy development.

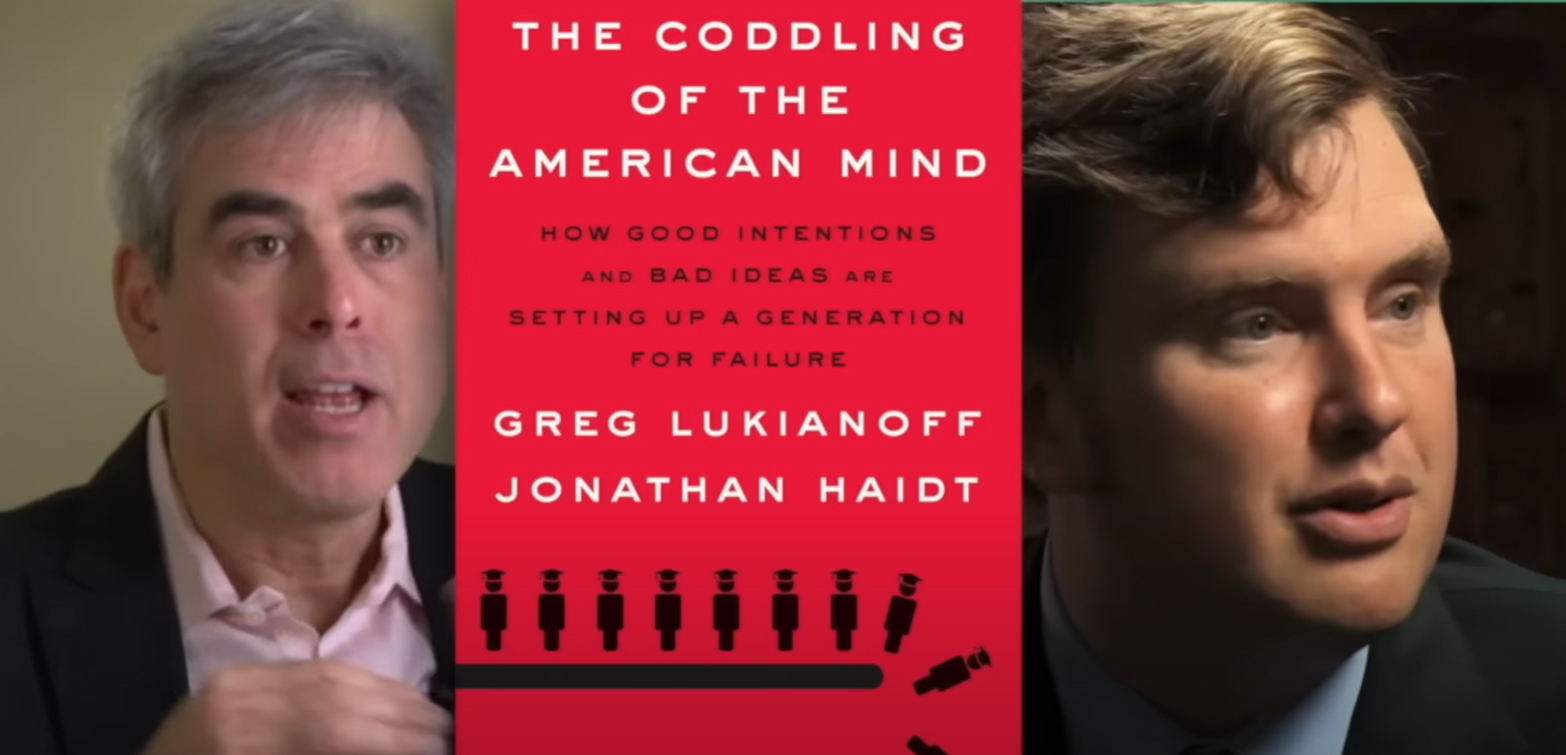

A previous book The Coddling of the American Mind, written by Haidt with his colleague Greg Lukianoff, describes “safetyism” as a cult which today has become equated not only with physical danger, but with emotional discomfort as well. They point out that since the 1980s, concepts like trauma and safety have moved away from legitimate psychological research and are now used to justify the overprotection of both children and college students. This has been especially so since 2013 when the internet generation started to enter college with increased demands for safe spaces and trigger warnings so high that attitudes toward speech and safety changed. The authors correlate this to the safety concerns that well-meaning parents and teachers had that curtailed unsupervised free play, resulting in youth unprepared for real-life situations. As the psychologist and authority on intergenerational differences Jean Twenge explains, many students nowadays believe that “one should be safe not just from car accidents and sexual assault but from people who disagree with you.”

Haidt points out that at the same time parents and society have become over-protective and overly concerned with safety in the real world, they have become distressingly under-protective and unconcerned about the harms of the online world. He characterizes smartphones as “experience blockers”: they “reduce interest in all non-screen-based forms of experience.” He identifies four fundamental harms of smartphones: social deprivation, sleep deprivation, attention fragmentation, and addiction. These harms result from repetitive, constant use, which may also cause structural changes in the brain. He presents alarming statistics including that teens spend 6 to 8 hours a day on screen-based leisure activities. Social media companies have been relentless in applying psychological techniques to capture and hold adolescents’ attention. Haidt refers to the work of developmental psychologist Laurence Steinberg who wrote that puberty makes the brain more malleable, or plastic. “This makes adolescence both a time of risk (because the brain’s plasticity increases the chances that exposure to a stressful experience will cause harm) but also a window of opportunity for advancing adolescents’ health and well-being (because the same brain plasticity makes adolescence a time when interventions to improve mental health may be more effective).” He emphasizes that this is a period in which our youth are much more vulnerable.

Girls are particularly susceptible to social comparisons, so the unrealistic images of beauty, perfection and popularity promulgated by various social media outlets have a particularly negative impact on girls’ well-being and mental health. Haidt argues that research demonstrates many of these negative impacts result directly from social media activity. (Elsewhere, he acknowledges that some scholars find current research inconclusive and thus his conclusions somewhat debatable). He also notes that the impact extends beyond the individual to the group, contributing to a rise in sociogenic illnesses, including anxiety and depression.

While some effects of the Great Rewiring are most notable in girls, others are particularly consequential for boys. Haidt reports that too much supervision and insufficient exposure to risk are especially problematic for boys. He cites data suggesting that Gen Z boys are taking fewer risks than they have historically. Although there are clearly some benefits from this reduced risk-taking (e.g., fewer accidents), there are also negative consequences for development. While acknowledging that the issue of video gaming is complicated (users are exposed to new experiences and can develop long-distance relationships), Haidt maintains that “the addictive design of these platforms reduces the time available for face-to-face play in the real world. The reduction is so severe that we might refer to smartphones and tablets in the hands of children as experience blockers.” Haidt also discusses the widespread availability of internet pornography. In addition to the risks posed by bad actors seeking to groom and connect with vulnerable girls and boys, boys are at risk of over-exposure to pornography, which has been shown to interfere with the development of their healthy real-world relationships.

Haidt sees the impact of the shift in emphasis from the real-world to the online world as adversely affecting not only our mental and physical health, but our spiritual well-being as well. He notes that social media trains us to make rapid judgments and think in ways that are completely opposite to the world’s wisdom traditions, some of which we have included on this site. When on social media, “we are processing events from an egocentric point of view — thinking about what I want, what I need to do next, or what other people think of me.”

In common with Ornstein, Armstrong and others, he agrees that “Self-transcendence is among the central features of spiritual experience.” Practices involving shared sacredness; embodiment; stillness, silence, and focus; finding awe in nature; becoming “slow to anger, quick to forgive” — all involve self-transcendence. (For more on the activation of this continuum and its importance for our future, see Activating Our Brain’s Latent Capacities.)

It’s not only that spiritual practices are all missing from the phone-based life, the author asserts that “The phone-based life produces spiritual degradation, not just in adolescents, but in all of us.” He suggests that whether one belongs to a formal religion or not, we need to seek out such practices and add them to our lives. We are pulled downwards by social media, but we can be pulled upwards by the simple act of eating, singing or playing together.

Haidt considers the Great Rewiring to be a social dilemma that requires collective action to solve. Problems like these are particularly sticky because they are defined by the presence of tension between an individual’s immediate self-interest or desire, and the long-term interests of the larger group. The result is a sort of trap, where the individual finds it hard to change in the absence of the entire group’s committing to change. For example, a parent might believe that their daughter would benefit from more unsupervised free play in the real world, but if no other children’s parents provide similar freedom (and might even report an unsupervised child to the authorities) then it will be hard for the girl’s parents to give her that experience. Peter Grey co-founded Let Grow to help address this issue.

Haidt offers multiple recommendations for how technology companies can help to reduce the harm of phone-based childhood. First, he argues that tech companies have a duty of care – that is, they have a moral and legal responsibility for how they treat minors. He also argues strongly that the age of “internet adulthood” should be 16 rather than the current 13, and that age should be verifiable by the providers – which is not currently the case – before access is granted. Haidt does not argue that children under age 16 should be prevented from accessing the internet but simply that younger children should not be able to enter into contracts with tech companies like Meta, which focus on capturing and holding user attention, the product they then sell to advertisers.

While improving safety in the online world is one part of the solution, addressing only the online world is not sufficient; Haidt says we must also address “safetyism” and over-protection in the real world. He advocates for increasing opportunities for real-world play and gives several suggestions for how to do so, including designing public spaces with this goal in mind. He maintains that parents should not be punished for giving children real-world freedom comparable to what many of today’s parents and grandparents experienced as children. He also argues for providing more vocational education, apprenticeship and youth development programs, again with the goal of giving adolescents real-world experience and responsibilities, and the accompanying feelings of agency and success.

Haidt has two major recommendations in The Anxious Generation for what schools can do to address the Great Rewiring: make schools phone-free and devote more time to free play. An unrelenting proponent of phone-free schools, Haidt cites evidence that smartphone access during school (even during lunch or on breaks) is detrimental to learning and to social engagement. Installing phone lockers is a straightforward step toward making phone-free schools a reality, he suggests, noting that when schools allow phones outside of class, during breaks and lunch for instance, students remain preoccupied with them when they return to class. Teachers are then forced to act as enforcers – a thankless and typically ineffective role. Furthermore, allowing phones in schools appears to be exacerbating disparities, with the most disadvantaged students suffering the greatest negative impact because they have less supervision and spend more time online than their counterparts.

His second recommendation seems quite feasible: increasing opportunities for free play. He suggests that schools a) provide longer recesses (with limited adult supervision), b) open school grounds for a half hour before school, and c) offer a “play club,” where kids of mixed ages could interact after school. Haidt maintains that these two interventions – restricting phone use during school, and increasing free play with limited adult supervision – would be more effective in addressing the current mental health crisis than if schools were to implement new social and emotional learning curricula or hire therapists.

Haidt also sees a crucial role for parents in addressing the Great Rewiring, writing that “we have vastly and needlessly overprotected our children in the real world” and stressing the need to instill feelings of responsibility and autonomy in children. He strenuously advocates for giving children more opportunities for free play, along with increased independence and responsibility in the real world, while delaying their entry into the phone-based world. Haidt recognizes that the thought of giving one’s children greater freedom is likely to be anxiety-provoking for some parents but believes that with time, as parents develop more and more trust in their child, the benefits will prove well worth the initial anxiety.

Noting that children and adolescents today often do not experience the rites of passage that marked transitions in earlier generations, he suggests ways parents might link particular birthdays to new freedoms and responsibilities. This approach could provide a structure facilitating healthy development in the real world and reducing the potential of harm from a phone-based childhood.

In conclusion, The Anxious Generation distills its recommendations down to four foundational reforms to help guide parents, schools, and society counteract the devastating impact of the Great Rewiring. These are:

- No smartphones before high school

- No social media before age 16

- Phone-free schools

- Far more unsupervised play and childhood independence

Haidt recognizes that while many people are experiencing a growing discomfort and awareness that something is wrong, as social animals we take our cues from others. When we look around to see if anyone else is reacting to the Great Rewiring, we see others who are also uncertain what to do. Haidt calls on all concerned readers to speak up and support these four reforms. He also encourages readers, and particularly parents, to connect with others to mutually support and encourage greater independence, responsibility and free play in childhood and adolescence. Speaking up and linking up are essential first steps in addressing this collective action problem.

The Coddling of the American Mind: How Overprotective Parenting Led to Fragility on Campus

The book is discussed by Lukianoff, a lawyer by training and who heads FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, which fights for free speech on campus. Haidt teaches at New York University and is a co-founder of Let Grow, the free-range parenting advocacy organization, and Heterodox Academy, which promotes intellectual diversity among faculty.

Since the publication of The Anxious Generation in March of 2024, Haidt has continued to advocate for mitigating the harmful effects of social media on adolescents and young adults. In a September 2024 Opinion piece in the New York Times, Haidt and collaborator Will Johnson (chief executive of the Harris Poll) reported results from a national survey of Gen Z adults (US adults aged 18 to 27). The survey was conducted in August 2024 and focused on Gen Z adults’ views on and experiences with social media. Findings show that nearly 60% of those surveyed report spending at least four hours a day on social media, and many spend even more. While just over half (52%) of those responding felt that they had benefited from social media, nearly one third (29%) believed they had suffered personal harm. Asked about various social media platforms and whether they wished each had “never been invented,” fully half of responding Gen Z adults (50%) wished that X/Twitter had never been invented. High rates of regret were also expressed for several other platforms: 47% wished TikTok had not been invented, 43% wished for no Snapchat, 37% wished for no Facebook and 34% wished for no Instagram. Lower but still substantial percentages wished for no smartphones (21%), messaging apps (19%), the internet (17%), Netflix (17%) and YouTube (15%).

Haidt and Johnson note that similar feelings of regret are common among users of addictive products (such as cigarettes) and activities (such as gambling). While there are measures in place to prevent young people from smoking or gambling, there are not currently comparable safety measures in place for social media. The Kids Online Safety Act, a bill currently under consideration by the US House of Representatives, would require social media companies to put a number of measures in place to protect children and young adolescents.

Watch Dr. Jean Twenge discuss the smartphone generation.