Multilateral and Bilateral Aid

Whether aid is given through multilateral organizations or bilaterally state-to-state, factors such as oppressive autocratic regimes, corruption, political and economic instability and the lack of civil rights in the recipient countries coupled with cronyism, inflexibility, fragmentation, and lack of in-country knowledge on the part of donors all impede its effectiveness.

Multilateral Aid–The UN, IMF and World Bank

Today, approximately 65–70% of aid is bilateral—given from one single state to another. The remaining 30–35% is multilateral—given through institutions such as the World Bank or the United Nations agencies. Multilateral aid is considered less politically motivated, encouraging international cooperation rather than the strategic and commercial interest of donor countries.

These institutions evolved from organizations originally created to contribute to post-war World War II reconstruction. The development work of the UN began with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency (UNRRA), founded during the war, and the World Bank, or the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which provided loans to recovering Western European nations.

Known collectively as the Bretton Woods Institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank were founded by the delegates of 44 nations in July 1944 in order to support the economies of their member nations. The agreement between these states introduced an adjustable pegged foreign exchange rate system. Currencies were pegged to gold and later to the US dollar.

The World Bank is primarily a development institution, which focuses on poverty reduction and improvement of living standards worldwide. Its initial stated goals were to bring financial support to the reconstruction of the countries that had been devastated by the Second World War and to grant loans to contribute to the development of “backward” countries (as developing countries were then called). The IMF was formed as a reaction to the Great Depression of the 1930s and is a cooperative institution between member states, which seeks to maintain an orderly system of payments and receipts between nations and has the authority to intervene when an imbalance of payments arises.

The World Bank Articles of Agreement, Article IV, Section 10, states: “The Bank and its officers shall not interfere in the political affairs of any member; nor shall they be influenced in their decisions by the political character of the member or members concerned. Only economic considerations shall be relevant to their decisions, and these considerations shall be weighed impartially in order to achieve the purposes stated in Article I.”

Since these loans must be provided “with due regard to the effect of international investment on business conditions in the territories of members,” the World Bank’s efforts, as NYU economist William Easterly points out in his book The Tyranny of Experts, “perfectly reflected a technocratic viewpoint—what mattered were the technical solutions to be implemented by the state, not the ‘political character’ of whether a state was authoritarian, abusive or corrupt.” This article made possible an alliance between those who wanted to fight global poverty with technocratic means and those with political motives. It enabled them to ignore the rights of the poor, and allowed tyranny to survive, believing and claiming that “benevolent” autocrats are better for rapid development.

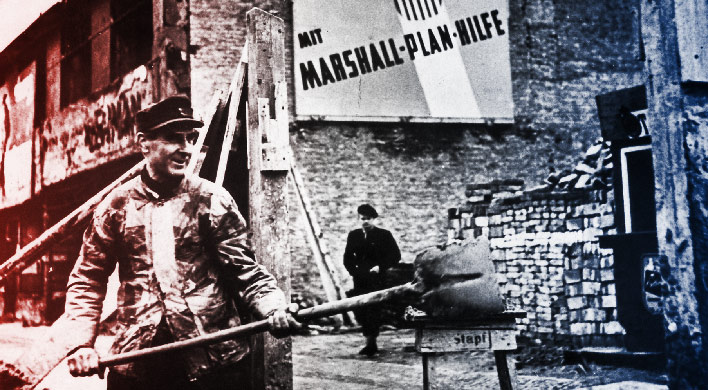

The Marshall Plan: Flawed Model for Developing Countries

From 1948–1951, the US injected $13 billion (in today’s money approximately $120 billion US, $11 billion of which were grants) to restore the economy and stability of seventeen European countries after the devastation of World War II. The Marshall Plan replaced the World Bank’s intervention since the US came to the conclusion that reconstruction gifts to Europe would be more efficient and cost-effective than loans.

By this time European vulnerability to Soviet Communism was evident and the consensus was that if the USSR was not prevented from extending its influence into Western Europe, then only the Atlantic would stand between it and the United States. Officially known as the European Recovery Program, the Marshall Plan prevented this and, importantly, it also ensured US access to European markets.

The Marshall Plan required these European nations to be responsible for a comprehensive and collaborative plan which would not merely alleviate their immediate predicament, but also enable them to eventually stand on their own. It was a success: it restored the confidence of Europe whose member states may not have otherwise recovered. So it is not surprising that its “success was seen as a model for development elsewhere.”

However, the histories of European nations were very different from those in the then Third World. European governments, institutions, their cities and infrastructure had evolved over centuries; the expertise needed to rebuild their devastated communities was available there, and the need to rebuild and reestablish themselves was self-evident. After the horrors of World War II, Europe was desperate to recover and live in peace.

Failure of the “Top Down” Model

The World Bank began its Third World development program in Colombia where it had a well-planned program of improvements and reforms, and believed that with a collective effort it could achieve its goals. Unfortunately, Colombia was going through a period of great political unrest. In 1948, Jorge Gaitán, a champion of Colombia’s poor majority, was expected to win the next presidential election, but was assassinated by a lone gunman in Bogotá. A riot raged for days before the army finally stepped in, then Conservatives declared a state of siege and closed Congress. Since the World Bank is prohibited from considering political upheaval or violence an obstacle to development, it unavoidably lent legitimacy to a brutal, repressive government. From 1948 to 1956, the political violence raged on, killing as many as 400,000 people.

The “top down” paradigm that [the IMF and World Bank] have adhered to from the beginning has resulted in vast sums being continuously misdirected.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the IMF and World Bank gave structural adjustment loans to poor countries which mandated changes in their economic policies that would encourage them to move to a free market economy. Such requirements included the liberalization of foreign exchange and import controls (freer trade), devaluation of the currency (encouraging exports), anti-inflationary programs including the abolition of price controls, and the promotion of foreign investment. These measures are meant to encourage responsible fiscal management in order to sponsor growth and sustainable development. Unfortunately, most of the recipient countries showed zero or negative growth and were unable to pay back their loans, falling further and further into debt.

The “top down” paradigm that these organizations have adhered to from the beginning has resulted in vast sums being continuously misdirected. According to the economist Angus Deaton, “The behavior of both donors and recipients is fundamentally affected by the existence and magnitude of these aid flows.” Aid stimulates government spending and frees leaders from the need to consult or gain the approval of their citizens, enabling dictators such as Zaire’s Mobutu and his regime to stay in power. Yet authoritarian regimes make up the bulk of aid recipients, and it is not unusual for donor countries to require aid agencies to channel money through recipient governments, rather than NGOs with good local experience and credentials, and give foreign aid to political allies who are corrupt, making these governments even less democratic.

Often, rather than help, aid efforts can inadvertently cause the poorest people unnecessary suffering. In 2005 in Mubende, Uganda, the national forest authority licensed thousands of acres of land to the British-based New Forests Company. With funding from the World Bank and others, the company planned to establish forests and then make timber products, including utility poles intended to deliver electricity to un-served parts of the country. Because of this program tens of thousands of farmers were forcibly evicted from their farms and livelihoods. Many refused to leave, and, five years later, in 2010 the forest authorities sent in armed agents to evict them.

Western donors believed they could achieve great results in Ethiopia by providing President Zenawi with expert advice and increased funding. But Zenawi was an oppressive ruler who rigged elections, jailed opponents, and shot protesters.

Again, to quote William Easterly, he even used donor funds to “blackmail starving peasants into supporting the regime and punishing opposition supporters by withholding donor-financed food relief.” In 2010, the Ethiopian government, in a program supported by the World Bank, relocated 1.5 million families far from essential services and sold their land to foreign investors. Families were forced to leave at gunpoint and many fled to refugee camps in Kenya. Human Rights Watch has condemned the World Bank for their involvement in this obligatory displacement.

Still Some Success

On the other side, in spite of the persistence of autocratic governments with their draconian laws and human rights abuses, according to Owen Barder, a senior fellow and director at the Center for Global Development, over the last three decades in Ethiopia international aid has made a difference, and there have been great improvements in Ethiopian development. During the 1980s famine in Ethiopia, about a million people were hit by drought and famine, and a quarter of a million people died of hunger. In 2008 another drought occurred but this time there was no famine. The Ethiopian government recognized the problem and was willing to do something about it. Early-warning systems put in with the support of donors recognized the problem early on so that food supplies were pre-positioned and “the world’s largest safety net” provided by donors was put in place, allowing people to stay in their homes and look after their crops and animals. So while a great deal of hardship and some hunger occurred, there was no famine. At the same time, across the border in Somalia where the government was not as effective there was a famine and a quarter of a million people died.

Sadly, in 2015 and 2016 the spring and summer rains failed again in Ethiopia, this time leading to starvation and desperation. Relief agencies warned that emergency food aid needed for 7.8 million people would run out in June of 2017. In 2020, other calamities added to food insecurity for East African countries, this time with flooding from exceptionally heavy rainfalls and the infestation of locusts—all at a time when these countries, as well as relief agencies and donor economies, are faced with the economic impacts of Covid-19.

Impact of Austerity

When the IMF insists that a country takes austerity measures, the results can disturb local politics. For example, having given Ecuador sixteen loans over a 40-year period, in the year 2000 the IMF enforced austerity measures, which caused an increase in fuel and electricity costs and a reduction in teacher salaries and resulted in political unrest.

UN Agencies

The United Nations has 193 member states and it comprises more than 30 affiliated organizations (including the World Bank and IMF) each with its own membership, leadership and budget processes, all working with and through the UN to promote worldwide peace and prosperity:

United Nations Development Program (UNDP) is the UN’s global development network, focusing on the challenges of democratic governance, poverty reduction, crisis prevention and recovery, energy and environment, and HIV/AIDS. UNDP also coordinates national and international efforts to achieve the Millennium Development Goals aimed at poverty reduction.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) protects refugees worldwide and facilitates their return home or resettlement.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) provides long-term humanitarian and development assistance to children and mothers.

World Food Program (WFP) aims to eradicate hunger and malnutrition and is the world’s largest humanitarian agency.

United Nations Drug Control Program (UNDCP) helps member states fight drugs, crime, and terrorism. Aside from providing laboratory services, this program helps to improve cross-border cooperation.

World Health Organization (WHO) is responsible for global vaccination campaigns, responding to public health emergencies, defending against pandemic influenza, and leading the way for eradication campaigns against life-threatening diseases like polio, malaria and Ebola.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) focuses on everything from teacher training to helping improve education worldwide to protecting important historical and cultural sites around the world.

In today’s world of changing scenarios and sudden crises, the efforts of some of these UN organizations are crucial. For example, the challenges facing the WHO are staggering, as populations increase and move around the world, as communities are forced to flee their countries and live in makeshift conditions.

Bilateral Aid

When aid is transferred from one single state to another it is termed bilateral aid. Since it accounts for 65–70% of the total aid, it has an enormous influence.

Donor countries tend to give bilaterally through their own international agencies to states known to them, or to states of economic and strategic interest. For example, the British and French prefer to give aid to their ex-colonies. Studies show that since the end of the Cold War, security-driven goals have become somewhat less dominant in United States foreign assistance policy, while ideological goals—particularly the promotion of democracy and good governance—have gained greater importance, prompting the US to increasingly reward fledgling democratic states with foreign aid. The understanding is that not only are democratic states more likely to distribute it equitably and create greater opportunities and benefits for the recipient society as a whole, but that civil rights and freedoms also correlate with less corruption and patronage.

Additionally, recipients of bilateral aid may be selected in response to pressures at home from political or business lobbyists, from ethnic groups who wish to support recipient countries, or from a public outcry, for example, at times of humanitarian disasters.

About 20% of foreign aid is “tied aid” which requires the recipient to spend a portion of the funds on goods and services from the donor nation.

Bilateral aid has a positive influence on the growth and development of the least developed countries, though the majority of them still do not have democratic rights, and thus in aggregate terms, aid is prone not to benefit recipients significantly. About 20% of foreign aid is “tied aid,” which requires the recipient to spend a portion of the funds on goods and services from the donor nation. Obviously, this benefits the donor country, creating jobs and an increase in exports, but it adversely affects the recipient country by preventing domestic manufacture of those products and services. It is also very costly.

Lessons and Challenges

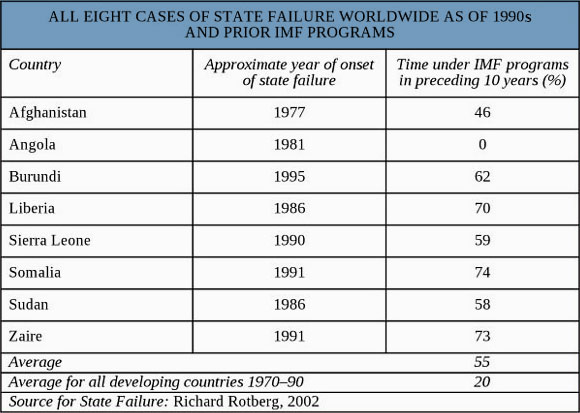

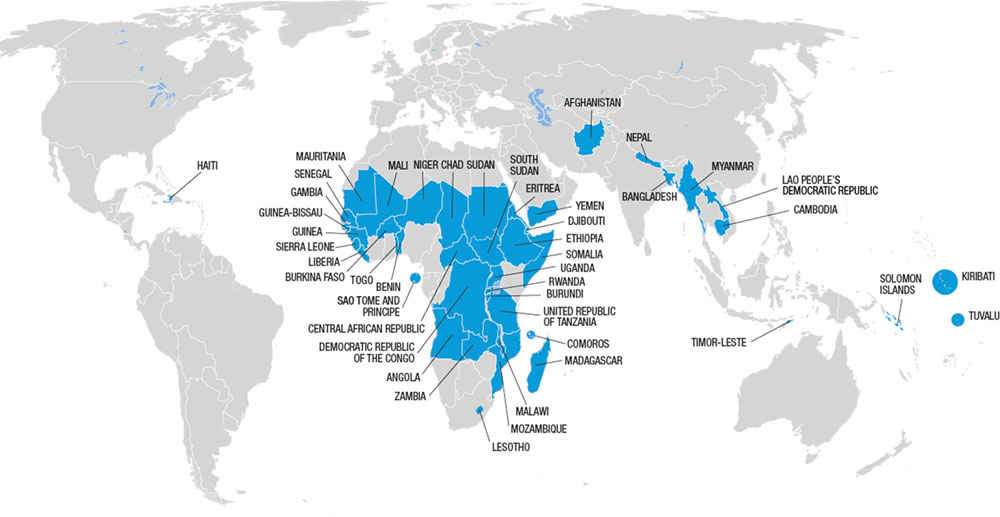

Obviously, aid is a complex phenomenon, and understanding the real situation from the outside can be extremely challenging. In general, though, it seems clear that countries that are too far gone politically and economically are less able to benefit from IMF involvement. Yet the IMF and World Bank have repeatedly given loans to countries with weak or problematic economic policies. Thirty-six countries in sub-Saharan Africa have received at least 10% of their income from aid for 30 years or more. For some, foreign aid has exceeded 75% of government expenditures, making them almost entirely dependent on it. Haiti has known only 5 years of democracy since it gained independence in 1804, and, according to Easterly, it has endured “almost two hundred coups, revolutions, insurrections, and civil wars since its independence.” In spite of this, from 1957 to 1986 Haiti received twenty-two loans from the IMF. Over this period, the Haitian government, mostly under the infamous Duvaliers, used poverty and ignorance to stay in power to such an extent that the average income declined. Political institutions failed to build, finance, and support schools, and economic institutions failed to create incentives for parents to educate their children, so school enrollment remained static at 50%.

In 2010, the World Bank and the IMF’s Global Monitoring Report advised that a major barrier to efficiency in providing aid was agency fragmentation.

The number of aid agencies has also grown enormously, with about 225 bilateral and 242 multilateral agencies funding more than 35,000 activities each year. A survey by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development revealed that in 2007 there were 15,229 donor missions to 54 countries—more than 800 to Vietnam alone. In 2010, the World Bank and the IMF’s Global Monitoring Report advised that a major barrier to efficiency in providing aid was agency fragmentation; and that it was essential to reduce this and to strengthen coordination between aid organizations. Nevertheless, according to a 2010 report from William Easterly and Claudia R. Williamson, Rhetoric versus Reality: The Best and Worst of Aid Agency Practices, both organizations continued to fragment aid to many countries. The share going to corrupt countries, which increased from the mid-1990s through 2002, has stayed around that level since then. Their study found these agencies had made no change: “the increase was due almost entirely to the fact that the same corrupt aid recipients had increased their corruption.”

“14 bilaterals have lower overhead costs than multilaterals, who in turn have lower cost ratios than UN agencies.”

They looked into bilateral agencies at the country level, multilateral agencies and UN agencies, using the same criteria that Easterly and his colleague Tobias Pfutze established in 2008. In addition to fragmentation and allocation of funds, they reviewed transparency, minimal overhead costs, and delivery to more effective channels. The Easterly-Williamson study found that the aid data in both multilateral and bilateral agencies is “of extremely poor quality and coverage, and what data is available shows very poor practices.” Both are signs, they say, of a fundamental lack of accountability of the official aid system to any kind of independent monitoring. “14 bilaterals have lower overhead costs than multilaterals, who in turn have lower cost ratios than UN agencies. The most extreme among the latter are UNDP and UNFPA, who actually spend more on administrative costs than aid disbursements (129% and 125%, respectively). UNDP also ranks last across all agencies recording the highest salary/aid ratio at 100%. The United States has the highest administrative costs of the bilaterals, plausibly reflecting the much-noted phenomenon that Congress has imposed many earmarks and other multiple and conflicting mandates on USAID.”

Aid organizations use global poverty estimates that are dependent on purchasing power parity (PPP) which is the exchange rate from one currency into another that would give the same purchasing power in both places. This is currently the equivalent of the purchasing power of $3.00 a day according to the World Bank. The numbers are unreliable and change whenever PPP rates are revised, but they are highly influential. As Nobel economist Angus Deaton says “Changes can have real effects if international organizations or NGOs shift their efforts to the places where they ‘see’ the highest poverty rates. … Much of the recent focus on African poverty postdates the 1993 revision and was arguably influenced by it.”

As Deaton and others have pointed out, donor governments don’t experience the effects of aid first-hand and in any case, because of cronyism, corruption and political affiliations, it’s rarely in their interest to withhold it. They prefer to give to countries, rather than people, and to give to as many countries as possible. As a result, small countries tend to receive more aid than large countries even though most of the world’s poor live in large countries. To satisfy their own donors, aid agencies can place a heavy administrative burden on the recipient government officials, taking them away from tasks that are more important. Such diversions can have serious consequences, particularly in small countries.

These agencies exist to do something about global poverty, working to approved budgets and plans. Not only do they lack the incentive to cut back if the aid is ineffective or even doing harm, their organizational inflexibility makes it virtually impossible.

Because governments can’t monitor the efforts of their aid agencies whose wide-ranging goals, such as poverty reduction, depend on so many factors, they rely on reports. These agencies exist to do something about global poverty, working to approved budgets and plans. Not only do they lack the incentive to cut back if the aid is ineffective or even doing harm, their organizational inflexibility makes it virtually impossible. More often than not, they employ bureaucrats in offices miles away from the country involved, who decide which goods and services to provide, with little feedback from recipients. In the absence of results, they publicize how much they have spent and focus on writing those reports and setting new goals, instead of running in-country research in to what interventions would help the poor and how to go about implementing them in a way that would work.

In 2000 the world leaders of 189 countries entered into a global commitment to achieve eight goals by the end of 2015. Called the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), these were:

- Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger

- Achieve Universal Primary Education

- Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women

- Reduce Child Mortality

- Improve Maternal Health

- Combat HIV/AIDS Malaria and other diseases

- Ensure Environmental Sustainability

- Develop a Global Partnerships for Development

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which concluded in 2015, were succeeded by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by all UN Member States. These goals provide a comprehensive blueprint for a more prosperous, sustainable, and equitable future, encompassing poverty reduction, education, health, equality, and environmental sustainability. While progress has been made in areas such as poverty alleviation, education, and healthcare, achieving lasting change requires bold political commitment, long-term planning, and integrated efforts that address the root causes of inequality and environmental degradation. By linking economic, social, and environmental dimensions and fostering coordinated action at every level, the SDGs call for strengthened partnerships and alignment of national policies to ensure that progress benefits everyone now and for generations to come.

External Stories and Videos

Rhetoric versus Reality: The Best and Worst of Aid Agency Practices

William Easterly & Claudia R. Williamson

Foreign aid critics, supporters, recipients and donors have produced eloquent rhetoric on the need for better aid practices – has this translated into reality? This paper attempts to monitor the best and worst of aid practices among bilateral, multilateral, and UN agencies.