Aegean Neolithic and Bronze Age Civilizations:

The Mycenaeans 1600–1100 BCE

The Mycenaeans were closely related to the Minoans. They both descended from early farmers who lived in Greece and southwestern Anatolia, which is now part of Turkey, and from people from the eastern Caucasus, near modern-day Iran.

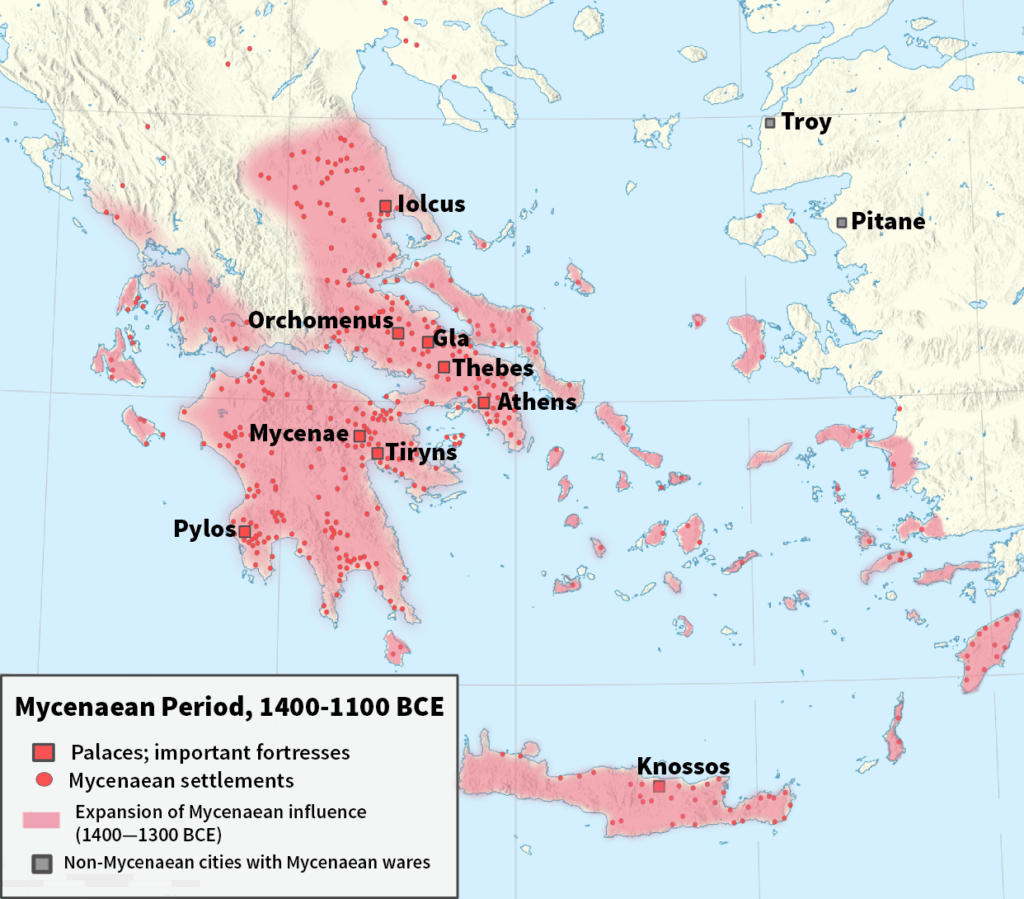

Called Achaeans in Homeric epic poems, by 1600 BCE a warrior class we know as the Mycenaeans, originating in the Peloponnese, had already conquered the native populations of central and southern Greece. In 1450 BCE Knossus and other “palaces” on Crete were sacked and destroyed by a combination of earthquakes and these invaders. They took over the Minoan trade routes in the Eastern Mediterranean and adopted and adapted their culture. They appear to have re-built the damaged palace of Knossos, which became an important base of operations and capital of the Mycenaeans until it was destroyed by fire in about 1375 BCE.

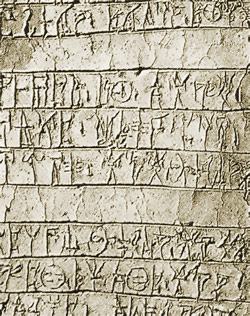

The Mycenaeans spoke an early form of Greek and adapted the Minoan Linear A syllabary (in which the written characters represent syllables rather than letters) to their own writing, now known as Linear B.

However, reading these texts tells us little about them: we learn the number of bulls or wagon wheels, for example, detailed inventories, bureaucratic records, accounts and taxes, but nothing about daily life.

The Mycenaean elites acquired a taste for Minoan goods and as a result imported Minoan craftsmen and artists as slaves to work in the dozen small kingdoms that came to dominate the Greek world, each headed by a wanax or “Lord” who ruled over the local population from fortressed palaces defended by chariot warriors. Later Greeks thought the massive walls and gates that protected the palaces had been built by a mythical race of giants known as the Cyclopes. These palaces were key to Mycenaean civilization. They were where the goods came from overseas, where literacy was confined to, and where slaves—mostly from Asia Minor came—bringing their skills in textiles, pottery and crafts.

Mycenaean frescoes clearly borrow the style of Minoan art. They display similar illustrations of lions and wingless griffins, and bulls are featured prominently. But the emphasis expressed in the Mycenaean art that remains seems to suggest the domination of man over the natural world: animals, for example, are now depicted as victims of the hunt. Archaeological remains also tell us that some Mycenaean Lords were fabulously wealthy, not only from trade but also from occasional piracy. Gold funeral masks, jewelry, bronze weapons, tripods, and a storeroom with 2,853 stemmed goblets have been found to attest to this.

Like the later classical Greek civilization, the Mycenaean Lords did not control religious life. People worshipped as they wished at the many cults and shrines often under the control of traditional priestly families. These religions were all almost certainly polytheistic. Most likely the Mycenaeans arrived in Greece with a pantheon of their own gods, headed by a ruling sky-god, which may have been Dyeus of the early Indo-Europeans. In later classical Greek, this god would become “Zeus,” and among the Hindus, “Dyaus Pitr.” As seen so often in the ancient world, they adopted and absorbed the religious traditions of the conquered population, so that once they took over Minoa, for example, their religious rituals would include honoring the Minoan goddesses.

They fought many civil wars, which we know from later legends, and established a settlement at Miletus on the Aegean shore of Asia Minor.

The Mycenaeans most likely arrived in Greece with a pantheon of their own gods, headed by a ruling sky-god which may have been Dyeus of the early Indo-Europeans. In later classical Greek, this god would become “Zeus,” and among the Hindus, “Dyaus Pitr”.

Miletus at the time was almost surrounded by water, a protected peninsula, that enabled easy trade with Asia Minor. Miletus became one of the leading cities, transmitting Aegean civilization across the larger peninsula. It was later known as the home of Thales, “the father of philosophy,” and became the commercial and intellectual capital of the Greek world in the century before Athens.

Mycenaean civilization was martial, based on seaborne trade, raiding and piracy. It was obviously important to keep trade open with the Near East. As a result, the Mycenaean Lords backed rebels and rivals of the Hittite Emperor along the southwestern rim of Asia Minor and were also active in Cyprus and along the Levantine shore and into Egypt.