Connecting with the Spirit World

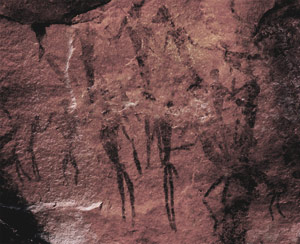

Prehistoric Aboriginal painting of Mini Spirits – Wikicommons

Many cave paintings were likely created as part of a ritual that took place in underground environments, and in which our ancient ancestors re-created and re-worked their out-of-body visions.

In their book Art and Human Development, Constance Milbrath and Cynthia Lightfoot cite anthropologist Abbé Henri Breuil’s report that “Salmon Reinach, the writer who first propagated the notion of sympathetic hunting magic, found that a Turkish officer whom he met was incapable of recognizing a drawing of a horse ‘because he could not move round it.’ Being a Muslim, the officer was entirely unfamiliar with depictive art.”

So, if two-dimensional representational art is not an innate human ability, how and why did it develop?

Says Lewis-Williams, “People didn’t one day invent making pictures. What happened was that people were familiar with the images that their brains were producing which were being projected onto cave walls and ceilings. And they wanted to nail down and make permanent those images, those visions that they saw.”

The South African archeologist and scholar David Lewis-Williams spent years studying and explaining the method and meaning of the art of the hunter-gatherer San peoples of South Africa. His work with the San included accumulating ethnological data, neurophysiological research and an in-depth study of the rock art of South Africa.

In 1995, he began a collaboration with the eminent prehistorian Jean Clottes. Together they studied 12 French caves with examples of Paleolithic parietal (or rock) art dating from the earliest Gravettian (26,000–20,000 BCE) period to the ancient, Middle and Upper Magdalenian (12,000–9000 BCE).

Both he and Clottes were familiar with many of the known religious traditions and art of other early peoples, for example in Siberia, the Americas and Australia.

They suggest that, like the images of the San and other shamanic artists, many of these Paleolithic images were created as part of a ritual that took place in the caves in which our early ancestors re-created and re-worked their out-of-body visions.

The very act of painting or engraving the images evoked these same animal spirits, or transformed shaman-spirit-animals, calling them from the underworld through the cave walls into their presence. In this way their supernatural power and the experience of it became palpable and accessible to those present.

Says Lewis-Williams, “People didn’t one day invent making pictures. What happened was that people were familiar with the images that their brains were producing which were being projected onto cave walls and ceilings. And they wanted to nail down and make permanent those images, those visions that they saw.”

Some images seem to have been created by spitting the ochre and charcoal onto the wall. The prehistoric art specialist Michel Lorblanchet, who has reproduced elements in this way, feels that this spit-painting, common among aboriginals, may have had a symbolic significance. “Human breath, the most profound expression of a human being, literally breathes life onto a cave wall. The painter projected his being onto the rock.” Moreover, the being of the shaman artist was the animal spirit. He or she was one with the image evoked.

The Shamans of Prehistory

Clottes and Lewis-Williams’ investigations of the caves lead them to conclude that not only their art but the layout of the caves themselves were employed to induce, control and exploit altered states of consciousness. In this way members of the community were initiated and became the world’s first ritual practitioners, priests or shamans.

As archeologist Paul G. Bahn reports in The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art, “…some of the art in deep caves appears to be ‘public’, being easily visible in large, readily accessible chambers. However, a great deal of it is undeniably ‘private’, in small niches, or chambers only accessible through a long journey or after negotiating difficult physical obstacles necessitating climbs, crawls or tight squeezes.

There are cases—as with the famous Ice Age clay bison of France’s Tuc d’Audoubert—where the very act of making the journey and of producing the images seems to have been what mattered; the artist(s) never returned to visit their work.”

Not only their art but the layout of the caves themselves were employed to induce, control and exploit altered states of consciousness.

Not only their art but the layout of the caves themselves were employed to induce, control and exploit altered states of consciousness.

To increase their chances of safety and survival, these people needed desperately to make sense of everything around them. Life and death were not hidden away, packaged and sanitized as they are in the societies of most of us but experienced by individuals every day. It seems very likely that during this early period the spirit world and its power was more—or, at least, as—present and essential as the world of everyday life.

Our early ancestors were animists, they experienced a vital spirit inherent in all things everywhere: humans, animals, plants, rocks, mountains, rivers, and the weather. Robert Wright points out in The Evolution of God that “…if you asked hunter-gatherers what their religion is, they wouldn’t know what you were talking about. The kinds of beliefs and rituals we label ‘religious’ are so tightly interwoven into their everyday thought and action that they don’t have a word for them. We may label some of their explanations of how the world works ‘supernatural’ and others ‘naturalistic,’ but those are our categories, not theirs.”

Given all that was against us, it’s hard to believe we could have survived solely by trial-and-error experiments. Our ancestors would have had to rely much more on their senses—including intuitive senses—than we do today.

There is good reason to believe that during this Upper Paleolithic Era, which dates from 50,000 to about 12,000 years ago—a period comprising most of human history— humans manifested mental abilities that are latent and less obvious in us all today. There were only a small number of people in existence then. One study suggests that the human population in Europe ranged from about 130,000 at its lowest point to about 410,000 during the severe cooling episode in the last glacial period about 13,000 years ago. The mean population density in the inhabited area varied between 2.8 and 5.1 persons per 100 square kilometers. (Compare that to an estimated 748 million in Europe in 2021, with a density of about 3,400 people per 100 square kilometers.)

Moving in small bands, these early hunter-gatherers endured unimaginable hardships. For many thousands of years freezing temperatures prevailed with very little respite. Endless snow and ice simply accumulated and deepened, covering Europe with glaciers. By about 20,000 BCE the landscape was dominated by glaciers. A mile-high polar ice cap enshrouded Scandinavia and most of northern Europe. Elsewhere harsh conditions favored grassland that provided fodder for large grazing mammals such as mammoth, bison, aurochs, horses, reindeer and elk.

Given all that was against us, it’s hard to believe we could have survived solely by trial-and-error experiments. Our ancestors would have had to rely much more on their senses—including intuitive senses—than we do today.

As the educator and scholar Idries Shah points out in his book Knowing How to Know:

“True, someone trying caraway seeds on infants might have discovered that an infusion of them quietened them. This he could transmit. But how could he, and those to whom he transmitted the information, forbear from trying all kinds of other preparations on children, destroying them faster than they could be replaced?

Just imagine the relatively small numbers of people in existence, the poor communications and wastage of transmitted information, the large number of possible trial-and-error experiments—and ask yourself how the human race survived this supposed period…. Then look at the persistent traditions among all people relating to the acquisition of knowledge and information from ‘supernatural’ or other sources….”

Our ancestors’ brains, though structurally the same at birth as our own, developed differently. Although they certainly had language, it would have been less dominant than it is today. Areas of the brain that are now taken up with the vocabularies of more than 50,000 words—and our ability to read them, as well as deal with spreadsheets, online banking, ever-changing technology and speed limits—were likely used to acquire different capacities that enabled them to survive. Even today, some remote tribespeople have an amazing capacity to navigate through the jungle or on the open sea.

In the book The Wind is my Mother: Life and Teachings of a Native American Shaman, the contemporary Muskogee Creek Indian shaman Bear Heart talks of the early days of his people: “The environment was our starting point in learning as much as we could from what was around us—the seasons, the things that grow, the animals, the birds, and various other life forms. Then we would begin the long process of trying to learn about that which is within ourselves. We didn’t have any textbooks, we didn’t have great psychiatrists who lived years ago and presented theories in this and that. We had to rely on something else, and that was our senses. Rather than through scientific investigation, we sensed those things within and around us.”

Bear Heart goes on to say that “children were encouraged to respect all inanimate and animate objects. Trees, for example, were their tall-standing brothers who emit energy all the time.” He describes one exercise where the children would be instructed to love the meeting place they were in; they were told to “put your heart into it.” Then they would be blindfolded and taken into the woods and required to find their way back. He writes that “the only way they could find their way back was by experiencing the love they felt before they went out.”

Today we have to learn almost everything—even metaphysics—through language. One spiritual teacher, the Sufi mystic Simab, explained:

“…you cannot think without words. You have been reared on books, your mind is so altered by books and lectures, by hearing and speaking, that the inward can only speak to you through the outward, whatever you pretend you can perceive.” —Idries Shah, Thinkers of the East.

In the 1950s the anthropologist Lorna Marshall published an incomparable record of the hunter-gatherer San people, Nyae Nyae !Kung Beliefs and Rights. She noted that about half the men in a !Kung or San camp in the Kalahari Desert were shamans and about a third of the women. Given that, and the extreme circumstances under which our early ancestors lived, it’s very likely that the ratio of Paleolithic peoples who experienced higher states of consciousness was considerably higher—initially perhaps the majority of people had this capacity.

Deep in the caves, in darkness or flickering torchlight, Paleolithic participants in shamanistic rituals would rhythmically move and perhaps chant. They would experience oxygen deprivation (anoxia), conditions that would destabilize them and help to induce a trance state. While in these altered states, they would communicate with the spirit worlds whose transferred power enabled them to solve a variety of problems: predicting the weather, foretelling the future, healing the sick, discerning what was edible, and choosing the right time to hunt specific animals.

What better way to survive than to seek to understand, harmonize and possibly acquire some control over these external forces, whether they be in this or the spirit world? As Karen Armstrong says in her book The Case for God, “The desire to cultivate a sense of the transcendent may be the defining human characteristic.” It began the moment we became modern man.

External Stories and Videos

The Dawn of Prehistoric Rock Art

James Q. Jacobs

With recent cave art discoveries and the accurate dating of the rock paintings, our concepts of human evolution have undergone significant transformations.

Watch: Talking Stone – Rock Art of the Cosos

Paul Goldsmith, ASC and Alan P. Garfinkel

Hidden away in the canyons of a top secret military base on the edge of the Mojave Desert is the largest concentration of rock art in North America. Created over thousands of years by a now vanished culture, it represents the oldest art in California. Talking Stone explores the remote canyons and mysteries surrounding these amazing images.