Creativity in Response to Crisis

Drawings of lions hunting bison in the End Chamber of Chauvet–Pont d’Arc, Ardèche, France. Britannica.com

The most intense artistic activity happened just as the Ice Age reached its most severe phase (approximately 40,000–15,000 years ago). Then about 10,000 years ago, it virtually disappeared as the Ice Age finally ended. Why were these sites selected, and how did these amazing images on cave walls function to help our ancestors survive their challenging situation?

“The ground is damp and slimy, we have to be very careful not to slip off the rocky way. It goes up and down, and then comes a very narrow passage about ten yards along through which you have to creep on all fours. And then again there come great halls and more narrow passages…. The tunnel is not much broader than my shoulders, nor higher…. With our arms pressed close to our sides, we wriggle forward on our stomachs, like snakes. The passage, in places, is hardly a foot high, so that you have to lay your face right on the earth. I felt as though I were creeping through a coffin. You cannot lift your head; you cannot breathe…. And so, yard by yard, one struggles on: some forty-odd yards in all. Nobody talks. The lamps are inched along and we push after. I hear the others groaning, my own heart is pounding, and it is difficult to breathe. It is terrible to have the roof so close to one’s head…. Will this thing never end? Then, suddenly, we are through, and everybody breathes. It is like redemption.”

This description by the paleontologist Herbert Kühn, from his book On the Track of Prehistoric Man, goes on to describe how the group, oxygen-deprived and exhausted, finally arrives inside “a colossal hall” whose walls portray layer after layer of amazingly vivid, lifelike beasts.

They are standing in the “Sanctuary” at Les Trois Frères, a cave in the Ariège region of southwestern France, surrounded by animals that roamed that area between 10,000 and 30,000 years ago. Looking upward, seemingly higher than any person could reach, they see a painted mythical figure, part-man, part-animal: the famed “Wizard” of Les Trois Frères, also known as the “Sorcerer,” who watches them from approximately 13 feet above their heads.

A similar almost intolerable rite of passage must be carried out when entering many of these ancient caves. If we’re right when we say that creative insight and actions flower in response to problems, we have to ask ourselves what possible purpose would these people have to undertake such difficult journeys to find dark, inaccessible, oxygen-deprived, noxious, gaseous caverns deep inside the earth and decide that this would be a great place to create art of such astounding beauty, accuracy and abundance?

Cave Paintings: Cosmic Maintenance and the First Recorded Stories

Within a 25,000-year period of the Ice Age—more than twelve times the age of Christianity—extraordinary cave art covered most of Europe, from Andalusia in Spain to the Ural Mountains of central Russia. Today we know of approximately three hundred sites, but scholars suggest there must have been thousands. Hopefully some have still to be discovered.

Some were created possibly to show how animals were tracked or to describe herd movements that not only aided hunting but might also have predicted climate change. Others may have been created for reasons of “Cosmic Maintenance,” functioning chiefly as part of a ritual whereby human beings connect and collaborate with the spirit world to assist in keeping the world and their survival in good working order.

In Chauvet Cave (southern France) dangerous animals such as cave bears, rhinoceroses, lions and even a spotted leopard are depicted. Scholars feel that these may well have been selected for their symbolic power. Cave images have been found, such as in the Lascaux Caves in southwestern France, that appear to have pockmarks made by pointed spears, possibly thrown in a ritual to “wound” the animal and so ensure future hunting success.

These artists were precise observers of the animals around them. They could define an animal’s rump, back, and body with a single line. Just a few more lines, and antlers and muscles stand out. A close look at these images reveals some unusual characteristics. Without grass or any other background, the animals appear to float in mid-air along these cave walls. Their hooves are undefined or left hanging, or a leg appears to end with the underside (a hoofprint) showing. Sometimes, as in the Axial Gallery at Lascaux, the paintings float upward and create what archeologist David Lewis-Williams called “a tunnel of floating, encircling images.”

Many images take advantage of the uneven walls; for example, a protrusion in the rock surface becomes a horse’s head looming out into the cave, or an edge or curve in a rock wall evoke—with just a few lines—a bison, lion or auroch emerging from the wall. Some images are engraved, others painted with fingers or charcoal.

Animals fly, swim or charge and are sometimes depicted wounded or dead. Dots, grids and patterns appear in places, and mysterious figures which combine animal and human characteristics, like the “Sorcerer” mentioned above, watched those who, long ago, entered these dark spaces carrying flickering tallow lamps.

Human skeletons have been found in the large rock shelters at cave entrances, but none in the caverns below where these images are found. It seems more likely that over thousands of years, these hidden spaces were used only for ritual practices. Handprints, both male and female, and some quite small suggest sacred areas where men and women and even children participated in rituals of initiation or celebration.

External Stories and Videos

The Dawn of Prehistoric Rock Art

James Q. Jacobs

With recent cave art discoveries and the accurate dating of the rock paintings, our concepts of human evolution have undergone significant transformations.

Why do We Tell Stories? Hunter-gatherers Shed Light on the Evolutionary Roots of Fiction

Daniel Smith, The Conversation

Given the ubiquity of storytelling, it may perform an important adaptive role in human societies by broadcasting social norms to coordinate social behavior and promote cooperation.

Neanderthals – Not Modern Humans – Were First Artists on Earth, Experts Claim

Ian Sample, The Guardian

Neanderthals painted on cave walls in Spain 65,000 years ago – tens of thousands of years before modern humans arrived.

Messages from the Stone Age

Robin McKie, The Guardian

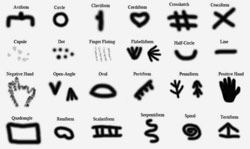

In Chauvet and Lascaux caves 26 specific signs are used repeatedly. These markings are no mere abstract scribbles but appear to be a code that was painted on to rock by the Cro-Magnon people, who lived in Europe 30,000 years ago.

Watch: Talking Stone – Rock Art of the Cosos

Paul Goldsmith, ASC and Alan P. Garfinkel

Hidden away in the canyons of a top secret military base on the edge of the Mojave Desert is the largest concentration of rock art in North America. Created over thousands of years by a now vanished culture, it represents the oldest art in California. Talking Stone explores the remote canyons and mysteries surrounding these amazing images.