The Human Trance State and the Idea of a Three-Tiered Universe

Modern shamanism, Wikimedia Commons

There is a common concept shared by different shamanic traditions around the world since prehistory, that cannot be accounted for by communication or migration, and is likely rooted in the human ability to access altered states.

Clottes and Lewis-Williams point out that although shamanic cultures are very different from one another, there are remarkable similarities that point to a basic human universal: the way the human nervous system behaves in altered states.

When they looked at how people became shamans, they found that all initiates either experience altered states involuntarily (hallucinations, visions, etc.) or took certain steps to induce them.

A Native American apprentice shaman might go on a vision quest, and, through hunger, pain, intense concentration and isolation from society induce a trance state where his spirit animal helper appears to him and he is filled with its supernatural potency. A South African San man or woman who wishes to become a shaman might dance with an experienced shaman until he or she achieves a trance state.

Prolonged privations, isolation, sacred places, rhythmic repetitive movements, chanting, protracted dancing, hyperventilation, intense concentration and hallucinogens are the elements selected and combined in various ways, depending upon the culture, as the individual seeks to achieve a deep trance state that connects him or her to the spirit world. The spirit encountered in this state bestows a supernatural power on the initiate. It is this power that enables an individual to function as a shaman, to address and solve the problems brought to him or her.

Neurophysiological studies of the trance state have shown that three overlapping stages can be identified:

At this point, we can say that our ancestors, not only physically but psychologically, became modern human beings. Our need to solve problems, seeking always to innovate and improve on previous solutions, together with our quest to understand the world and our place in it—our current human journey—began here.

In stage one, people “see” geometric forms, which can be brightly colored, flicker and pulsate, enlarging, contracting and blending one with another.

Second, the geometric forms are illusioned into objects of religious or emotional significance.

The third state, as Clottes and Lewis-Williams describe in The Shamans of Prehistory, “…is reached via a vortex, or tunnel. Subjects feel themselves drawn into the vortex, at the end of which is a bright light. On the sides of the vortex is a lattice derived from the geometric imagery of Stage One. In the compartments of this lattice are the first true hallucinations of people, animals, and so forth.”

These are described as like projected images, floating across animated surfaces, walls and ceilings. The scholars note that what the subject “sees” in this third stage is culturally determined: people see what they expect to see. A shaman might “see” an animal spirit, a Christian mystic, her favorite saint.

In this third stage hunter-gatherer societies believe that a shaman’s spirit leaves his body. Often people feel they can fly and change into birds or animals—become one with their hallucination, so to speak. Quite frequently the subject descends into the underworld.

According to Clottes and Lewis-Williams:

“The ubiquity among shamanic groups of beliefs concerning descent into the earth may be explained by the neurologically generated sensations of the vortex that draws people into the third and deepest stage of trance, the state in which they experience hallucinations of animals, monsters, and so forth. The vortex creates sensations of darkness, constriction, and, sometimes, difficulty in breathing. Entry into an actual hole in the ground or a cave replicates and is a physical enactment of this neuropsychological experience….

“But entry into a cave does not only replicate the vortex; it may also induce altered states of consciousness. The social isolation, sensory deprivation, and cold that characterize caves are important factors in the induction of trance. During the Upper Paleolithic, entry into an actual cave may therefore have been seen as virtually the same thing as entry into deep trance via the vortex. The hallucinations induced by entry into and isolation in a cave probably combined with the images already on the walls to create a rich and animated spiritual realm. A complex link between caves and altered states seems undeniable.”

So shamans universally operate within a tiered cosmos. From the everyday world, they can fly to the spirits above and descend to the spirits below. This, too, is reflected in the three-tiered world of the Paleolithic caves, selected because they would help induce the states of consciousness that connected the initiates to the spirit worlds.

Our Three-Tiered Universe

At this point, we can say that our ancestors, not only physically but psychologically, became modern human beings. Our need to solve problems, seeking always to innovate and improve on previous solutions, together with our quest to understand the world and our place in it—our current human journey—began here.

As Steven Mithen writes in Thoughtful Foragers: A Study of Prehistoric Decision Making, “This art was part of modern human ecological adaptation to their environment. The art functioned to extend human memory, to hold concepts which are difficult for minds to grasp, and to instigate creative thinking about the solution of environmental and social problems.”

Paleolithic people responded to the way caves were structured, their topography, passages and chambers reflected this tiered cosmos—the awe of the arched roof, the ground-level gathering places of ritual and the narrow passageways that lead to the cavernous crypts below. It was at this point in our history that we first began to conceive of a three-tiered cosmos—a world below our world and one above—and to formulate rituals to encounter forces above and below that influence our life and that might in turn be influenced by us, an idea that has been with us ever since.

From this early time to the present day, shamans and priests of all persuasions universally operate within this tiered cosmos. From the everyday world, they can fly upwards to intercede with heavenly spirits and can honor or fear the dead and unknown in the spirit world below.

The idea of a tiered cosmos has persisted in ritual and religious architecture for 35,000 years.

A Priesthood Emerges

The archeologist Abbé Breuil noted that the “Sorcerer” at Les Trois Frères that we mentioned above, was deliberately placed “four metres above the floor in an apparently inaccessible position, only to be reached by a secret corridor climbing upwards in a spiral” [italics ours]. So it seems that by about 14,000 years ago, the shaman’s elite role was evolving.

At Lascaux (15,000 BCE), the westward-facing entrance has a 12° downward slope that leads to the paintings in a large cavern known as the Hall of the Bulls. At the sunset of the Summer Solstice, the sun’s rays penetrate far into the cave and reach the Hall of the Bulls where they illuminate several already awe-inspiring paintings. This is the first evidence we have of the shaman priesthood harnessing the power of the Sun, a god that in the next Neolithic era would be worshipped in megalithic temples constructed by thousands under the direction of the priesthood.

As the Ice Age ended and populations increased, the experience of the shamans—their art, stories and predictions—would set them apart from the rest of society. They would become an elite, specialized group destined to travel a unique path in humanity’s search for deeper understanding and transcendence. They held the key to meaning for these very early communities and would do so—in one guise or another—for many millennia.

External Stories and Videos

Why do We Tell Stories? Hunter-gatherers Shed Light on the Evolutionary Roots of Fiction

Daniel Smith, The Conversation

Given the ubiquity of storytelling, it may perform an important adaptive role in human societies by broadcasting social norms to coordinate social behavior and promote cooperation.

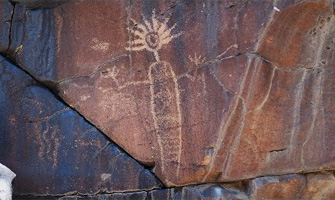

The Dawn of Prehistoric Rock Art

James Q. Jacobs

With recent cave art discoveries and the accurate dating of the rock paintings, our concepts of human evolution have undergone significant transformations.

Neanderthals—Not Modern Humans—Were First Artists on Earth, Experts Claim

Ian Sample, The Guardian

Neanderthals painted on cave walls in Spain 65,000 years ago – tens of thousands of years before modern humans arrived.

Talking Stone–Rock Art of the Cosos

Paul Goldsmith, ASC and Alan P. Garfinkel

Hidden away in the canyons of a top secret military base on the edge of the Mojave Desert is the largest concentration of rock art in North America. Created over thousands of years by a now vanished culture, it represents the oldest art in California. Talking Stone explores the remote canyons and mysteries surrounding these amazing images.