The Prehistoric Use of Sound in Caves

Concert Hall in Postojna Cave, Wikimedia Commons

Subterranean echoes were very likely understood by our Paleolithic ancestors to be the voices of spirits. Their reverberating acoustics appeared to come from deep inside the cave walls, thought to be portals to the spirit world.

Subterranean caverns provide such silence that one might hear one’s own heartbeat. In some instances, this probably contributed to sensory deprivation among our Paleolithic ancestors, and which has been known to induce altered states of consciousness. On the other hand, the acoustic properties of caves appear to be extremely important. Though he has yet to make a systematic study, Steve Waller, an expert in the study of archaeoacoustics found that 100% of the sites he studied that have acoustic properties also have paintings, while those that don’t have acoustic properties or have less of them, have few or no paintings. One can imagine a shaman initially experiencing a vision journey when visiting such a place: the exertion spent getting there, the dead silence, the anoxia and the astounding echo reverberation from any noise he or she inadvertently made would all contribute to the experience.

It seems evident that sites, once selected by the shaman, served multiple purposes. Instruments such as flutes and conch shells have been found. Such instruments, together with repetitive percussive sounds and human vocalizations whether in speech, chant, song or mimicry of animal sounds, would have provided an alternative gateway to a trancelike condition. In 1993 Waller observed that since 90% of the animals depicted on cave walls are hooved, it is conceivable that percussive sounds from clapping or striking stone or bone objects together would be part of a ritual, repeatedly echoing sounds of the galloping hooves of horses, auroch and buffalo as they mysteriously appear and disappear in oscillating torchlight.

Echoes fool the ears because they seem to have multiple sources. These ancient sound artists may have taken advantage of this perceptual ambiguity to destabilize participants.

Acoustics in the Caves

In terms of acoustics, a cave is a “room” with a much more complex set of inter-connected spaces than we typically experience in a regular room. Whatever its physical characteristics, a sound wave radiates from a source and travels on a straight-line path, outwards in space and time to a listener in another location. But in a cave, the sound wave continues to travel onwards until it is reflected from a wall of the cave (i.e., any lateral boundary, or ceiling or floor). It then has a new path until the reverberant sound reaches another obstacle and on to the next one. Depending upon where she is, the listener receives a succession of reverberations of the original sound that gradually diminish in amplitude. Inside these multileveled caves the reverberation might sustain even a brief sound such as a hand clap for several or even many seconds.

Since we have ears on both sides of our heads, a sound vibration arrives at one ear at a slightly different time and amplitude from the other ear, dependent on the location of the sound source. To pinpoint the source of a sound, our brains process the different neural signals generated within each of our inner ears. This extraordinary ability enables us to identify a sound source – saber-toothed tiger coming towards us from the left, friends approaching the cave entrance in front, etc.

Lower frequency sound reverberates for a longer time than higher frequencies, which are more readily absorbed by the walls. The adult male voice has a range from about 85 to 155 Hz in speech, whereas the adult female vocal range is about 165 to 255 Hz, almost one octave higher. Humans can hear a sound down to a lowest frequency of 20 Hz. Sub-sonic frequencies below 20 Hz up to 100 Hz or so are “felt” by the body, with the tactile sensation most sensitive around the lips, mouth and fingertips. One’s whole body responds to low-frequency sounds of very large amplitude, and such sounds would be amplified within the enclosure of a cave creating an awesome experience. As with today’s subwoofers that deliver the lower frequencies of 20-200 Hz, participants would not have just heard these sensations as sound but also felt them as vibration.

Strong late reflections are heard as an echo that is distinct from the background reverberation. This is where the complex shape of a cave has a more pronounced perceptual effect than a generic room. For example, sound reflected from a source along a passageway of at least 25 feet in length would lead to an audible echo for a listener at the entrance to the passageway. Potential participants might hear the distant rumble from several miles away and know it was time to join a ritual or celebration. As our ancestors made their way towards the mouth of a cave, they would hear the male voice or the pulsing drumbeats long before they arrived. And, as they approached, any vocalization they made outside the cave would return a strong echo coming from its entrance – the source, so to speak, of the spirit world.

External Stories and Videos

Watch: A series of short videos illustrate the properties of sound waves and how they are transmitted and perceived

Watch: The oldest identifiable musical instrument so far found is a flute, dated 42,000 to 43,000 years ago.

Such flutes were made from vulture bones and ivory from mammoth tusks. This one was found in the Swabian Jura mountains in southern Germany along with a bullroarer, which might have been used for dramatic effect. with a carved set of lines on it that resemble those found in cave paintings, indicating a trance state.

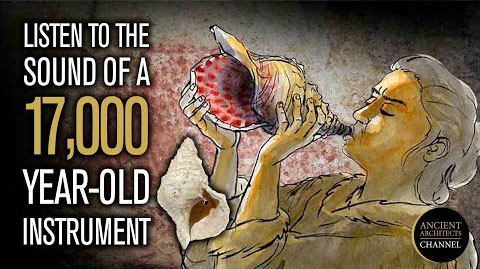

Watch: A large conch shell (31 cm long and 18 cm wide) was found in 1931 in the Marsoulas Upper Paleolithic cave in Southern France near the Pyrenean foothills.

It is decorated with fingerprints applied in red ochre that are similar to those found in the wall paintings in the cave. It was originally thought to have been used as a ceremonial cup, until new analyses in 2021 revealed that the shell was modified to be used as a musical wind instrument.