Book Review

Foragers, Farmers, and Fossil Fuels

How Human Values Evolve

Ian Morris

Paperback edition 2015

Reviewed by George Kasabov

Contributing Writer

How has the amount of energy that could be captured in each stage of human development affected our values and attitudes to fairness and justice? What can we can learn about humanity by looking back to long before there was a written record, before we took up farming, a time when we were all still hunter gatherers, and then from there going past agrarian times right up to the present day, a time when we are reliant on fossil fuels—and beyond? How have climate change, mass migration, epidemic disease, and state failure affected each period of history?

Back in 1982, as a young archaeologist, Ian Morris went on an excavation to Assiros, a farming village in Northern Greece. One evening an old farmer passed by on the dusty road, riding side-saddle on his donkey. Beside him walked his wizened old wife, bent low under the weight of a bulging sack.

“The old man stopped, all smiles. He exchanged a few sentences with our spokesman, and then the little party trudged on.“

“That was Mr. George,” our interpreter explained.

“What did you ask him?” one of us said.

“How he’s doing. And why his wife isn’t riding the donkey.”

There was a pause. “And?”

“He says she doesn’t have one.”

“It was my first taste of the classic anthropological experience of culture shock.” writes Morris. “ Back in Birmingham [UK], a man who rode a donkey while his wife struggled with a huge sack would have seemed selfish (or worse). Here in Assiros, however, the arrangement was clearly so natural, and the reasons for it so self-evident, that our question apparently struck Mr. George as simpleminded.”

More than 30 years later, in 2015, Morris wrote Foragers, Farmers, and Fossil Fuels: How Human Values Evolve to explain why his take on human values is so different from that of Mr. George.

He argues that certain basic human values, such as “treating people fairly, being just, love and hate, preventing harm, agreeing that some things are sacred” arose around 100,000 years ago. These “core concerns,” which recur in every culture in some form, were enabled by “the biological evolution of our big, fast brains,” and some of these values are shared to some extent by our “closest kin among the great apes.”

Morris points to three successive stages of human development, defined by progressively more productive modes of energy capture: foraging, farming, and fossil-fuel production. He asserts that each of these modes of energy capture “determine” or at least “limit” the possible forms of social organization, and therefore the social values that prevail. It is the “modes of energy capture [that] determined population size and density, which in turn largely determined which forms of social organization worked best, which went on to make certain sets of values more successful and attractive than others.”

So, early societies that made a living by foraging (hunting and gathering) tended to adopt social structures and values that were egalitarian—that involved strong norms of sharing and limited inequality—while also being quite violent. Farming societies tended to be hierarchical, with large gaps of inequality (as with Mr. and Mrs. George) and to be less violent. While fossil-fuel societies, which began in the eighteenth century, tend to be more egalitarian with respect to politics and gender, fairly tolerant of wealth inequalities, and much less violent than those before.

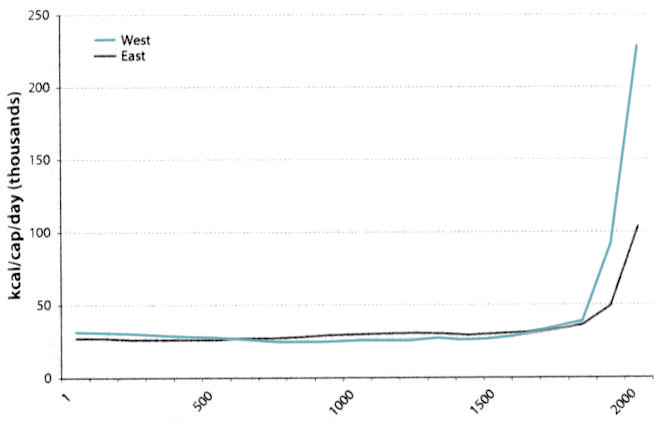

In an earlier book, Why the West Rules—for Now: The Patterns of History and What They Reveal About the Future, Morris compared how well the human race has done in the East and the West during the last 15,000 years. He argued that it is “latitudes not attitudes,” that is, physical geography, rather than culture, religion, politics, genetics or great men, that explains why the West dominates the globe—for now.

His aim was to explain why the West was more developed early on, how it lost its lead for a thousand years after the fall of the Roman empire, and then forged ahead again in the last two centuries. However, as things are now changing, he suggests that “knowing why the West rules gives us a pretty good sense of how things will turn out in the twenty-first century.”

Like Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs and Steel, Morris points to the significance of the East/West layout of the Eurasian continent and its location in one of what he terms the “lucky latitudes”—climate zones which are generally good for agriculture and pasturage. This is distinct from the North/South orientation of the African and American landmasses, which, as they span a dramatic variety of climate zones, form barriers to the cultural and biological transmission which occurred easily across the Eurasian continent.

Once mankind had settled down to agriculture and herding, there began a back and forth movement between what Morris terms Low End states and High End states, jostling each other for pre-eminence.

The Low End states he defines as feudal mafias, like the kingdoms of Europe in the dark ages, in which strong men vie for position in an environment with few resources. The High End states are much more complex and stable. They became extractive empires, like ancient Rome, Persia, or China in which an aristocratic class found ways to martial a large population and tax it so as to pay for an invincible army, an army that could protect the empire, control it, and extend it. How these low and high end states competed was constrained by geography, technology, and five critical, interrelated challenges that Morris calls the Five Horsemen of the Apocalypse:

- famine

- plague

- climate change

- unstoppable migration

- state failure

When societies failed to solve these problems, decline turned into disastrous, centuries-long collapse and a dark age.

For the past 10,000 years, all large societies have faced the five horsemen. They appear time and again. For instance, from 800 to 500 BCE the climate cooled. In Northern Europe, the population fell, but in the Mediterranean region it rose. At the same time cold winds from Siberia blew down into China, making the climate drier. Raymond Bradley, the author of a standard textbook on paleoclimatology, says of these years “If such a disruption of the climate system were to occur today, the social, economic, and political consequences would be nothing short of catastrophic.”

As for the recurrent menace of plague: “Whatever the mechanisms of microbial exchange, terrible epidemics recurred every generation or so from the 180s CE on. In the West the worst years were 251–266, when for a while five thousand people died each day in the city of Rome. In the East the darkest days came between 310 and 322, beginning again in the northwest, where (according to reports) almost everyone died… Cities shrank, trade declined, tax revenues fell, and fields were abandoned. And as if all this were not enough… the weather, too, turned against humanity, ending the Roman Warm Period. Average temperatures fell about 2°F between 200 and 500 CE, and since the cooler summers of what climatologists call the Dark Age Cold Period reduced evaporation from the oceans and weakened the monsoon winds, rainfall declined as well.”

So “this time, disease and climate change—two of the five horsemen of the apocalypse …were riding together. What that would mean, and whether the other three horsemen of famine, migration, and state failure would join them, would depend on how people reacted.”

As a way to explain historic patterns and predict future trends, Morris devised a Social Development Index which increases and declines through time, along with the rise and fall of each civilization. The index considers four factors:

- the amount of energy per person the civilization can usefully capture;

- its ability to organize, measured by the size of its largest cities;

- its war-making capability—weapons, troops strength, and logistics; and

- the speed and reach of its information technology—writing, printing, telecommunications, etc.

Though the West has dominated since the latter part of the 18th century, there is now a relentless transfer of power to the East that, in Morris’ opinion, is inevitable. His index projects that at the 21st century rate, the East would catch up with the West and the lines would cross in the year 2103. But the pace is likely to accelerate—so he predicts that the gap will disappear sometime in the middle of this century.

In Foragers, Farmers and Fossil Fuels: How Human Values Evolve, Morris develops the claim that changes of attitudes to fairness and justice are related to how much energy humans could capture as their way of life changed at different stages of history. As it says on the book’s flyleaf:

Most people in the world today think democracy and gender equality are good, and that violence and wealth inequality are bad. But most people who lived during the 10,000 years before the nineteenth century thought just the opposite. Drawing on archaeology, anthropology, biology, and history, Ian Morris explains why.

“Fundamental long-term changes in values,” Morris argues, “are driven by the most basic force of all: energy…”

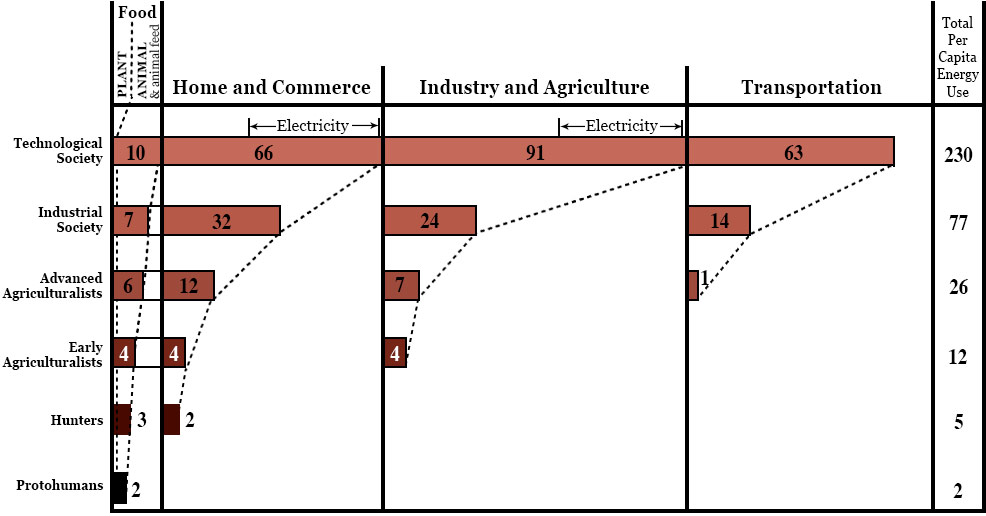

Foragers (hunter gatherers) could only capture 4–5,000 kilocalories per person per day—only enough to eat and keep warm as they roamed about searching for food. Because of their lifestyle, he claims that foragers value political and wealth equality, with little or no hierarchy, some measure of gender equality, and acceptance of considerable inter-personal violence.

“Fundamental long-term changes in values,” Morris argues, “are driven by the most basic force of all: energy.”

Farmers, who could capture 10–30,000 kcal per person per day, used their surplus to form complex and highly stratified sedentary societies that could support far greater numbers and develop technologies unavailable to the mobile foragers. As farmers cannot move about, living in much larger societies tied to the land of necessity, they had to work out ways to organize and protect themselves. This resulted in hierarchically stratified states in which political and wealth inequality was accepted as utterly natural, as was gender inequality. While interpersonal violence was somewhat reduced, state violence was endemic and expected.

Now we, the Fossil Fuelers, have captured up to 230,000 kcal per person per day, and since the late 18th century have been able to achieve the unimaginable—for now. This has been a period during which the West espoused open democracy as a desirable aim, though much of the rest of the world remains under despotism (remember, the book was published in 2015, before the worldwide trend to populism became evident—a trend which could be interpreted as resulting from some of the five horsemen). So Morris’ contention that fossil fuel made democracy desirable is only true in those parts of the world which have been sufficiently enriched by the early adoption of fossil fuels.

We in the West have seen a radical reversal of ideas. Instead of the previous acceptance of inequality as a natural condition of mankind, we now assume that political equality is possible, and we have an unrequited aspiration for equality of wealth and gender. Also, violence, which was accepted as a fact of life, is now considered unacceptable (even if it still goes on and on).

Finally, Morris speculates about what options there may be in times to come, given the possibilities and constraints of energy capture, climate change, migration, disease and state failure. He points out that we have entered a period of even faster change, in which geography will continue to be unfair. “Global warming will raise crop yields in cold, rich countries such as Russia and Canada, but will have the opposite effect in what the U.S. National Intelligence Council calls an ‘arc of instability’ stretching from Africa through Asia … Most of the poorest people in the world live in this arc, and declining harvests could potentially unleash the last three horsemen of the apocalypse… the Stern Review concluded that by 2050 hunger and drought will set 200 million ‘climate migrants’ moving—five times as many as the world’s entire refugee population in 2008. …

“Air travel has made disease much harder to contain… The world may be on the brink of another pandemic.

• All countries will be affected.

• Medical supplies will be inadequate.

• Large numbers of deaths will occur.

• Economic and social disruption will be great. As when the horsemen rode in the past, climate change, famine, migration, and disease will probably feed back on one another, unleashing the fifth horseman, state failure.”

“Collapse can be fast or slow. But either way, we have to ask the question: then what? [A few nuclear] missiles, …could kill most of us, and the unhappy few who remained might well … shoot each other or scatter and starve in an irradiated wasteland. Alternatively, incoming tides of germs might wash over the suburbs, or rising temperatures might gradually dry up shipments of food to Safeway and Trader Joe’s. When the ancient equivalent of this happened in Italy between AD 439 and 600, the city of Rome shrank from about 800,000 people to fewer than 40,000.”

Perhaps “collapse—especially the slow kinds—will not turn the clock back to the age of foragers. The world still has plenty of people who do know how to do things… Plenty of these people farm, know how to generate electricity with bicycles and build shortwave radios, and can make beat-up old trucks run on biofuels. No few of them have guns and have been preparing for the end days for some time now. And for all the things they do not know how to do, there will still be books. Many of these will surely be lost, and we might need characters like the hero of Walter Miller’s science fiction classic ‘A Canticle for Leibowitz,’ working secretly to preserve the world’s stock of knowledge; but we will not regress to a preliterate, prescientific, foraging world.”

Maybe “the most likely outcome is a hybrid economy… In some ways, it could look rather like the early twentieth century AD, before the computer age began; in others, more like the twentieth century BC. I imagine the overall effect as something like the chaotic, semi-industrialized landscape of failed states in sub-Saharan Africa. When the Western Roman Empire fell apart between the fifth and seventh centuries AD, skills that remained useful survived, those that did not disappeared, and people applied common sense and adjusted their values to the messy new realities. Much the same, I would guess, awaits the survivors of a twenty-first-century catastrophe.” An unhappy time to come.

Morris finishes with a quote from the historian Yuval Noah Harari, who sees storytelling as the key to the human condition and ends his book Sapiens by asking, “Since we might soon be able to engineer our desires, perhaps the real question facing us is not ‘What do we want to become?,’ but ‘What do we want to want?’ … Perhaps the real question is not ‘What do we want to want?’, but ‘What are we going to want, whether we want to want it or not?’”

Rescuing the Planet

Protecting Half the Planet to Heal the Earth

Tony Hiss

Could it be possible to set aside half the earth’s land and sea for nature by the year 2050? Former New Yorker staff writer Tony Hiss investigated the feasibility of this ambitious idea proposed by biologist Edward O. Wilson and emerged inspired and surprisingly optimistic.

The Future

Six Drivers of Global Change

Al Gore

No period in global history resembles what humanity is about to experience. Explore the key global forces converging to create the complexity of change, our crisis of confidence in facing the options, and how we can take charge of our destiny.

Our Choice

A Plan to Solve the Climate Crisis

Al Gore

We clearly have the tools to solve the climate crisis. The only thing missing is collective will. We must understand the science of climate change and the ways we can better generate and use energy.

The Big Ratchet

How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis

Ruth DeFries

Human history can be viewed as a repeating spiral of ingenuity—ratchet (technological breakthrough), hatchet (resulting natural disaster), and pivot (inventing new solutions). Whether we can pivot effectively from the last Big Ratchet remains to be seen.

The Sixth Extinction

An Unnatural History

Elizabeth Kolbert

With all of Earth’s five mass extinctions, the climate changed faster than any species could adapt. The current extinction has the same random and rapid properties, but it’s unique in that it’s caused entirely by the actions of a single species—humans.

Natural Capitalism

Creating the Next Industrial Revolution

Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins & L. Hunter Lovins

A new definition of capitalism that fully values natural and human resources may hold the keys to a sustainable future.

In the series: A Sustainable Planet

- Our Finite Planet

- Our Climate Crisis—and What We Can Do About It

- The Rocky Road to a Sustainable Future

- Our Looming Global Water Crisis

- Our Plastic Earth

- Rescuing the Planet by Tony Hiss

- The Future: Six Drivers of Global Change

- Our Choice: A Plan to Solve the Climate Crisis

- The Big Ratchet

- The Sixth Extinction

- Natural Capitalism

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Why the West Rules—For Now

Ian Morris, The RSA

Combining history, anthropology and social science, Stanford historian and archaeologist Ian Morris looks afresh at our global past, present and future.

Why Inequality and Violence are Sometimes Good: The Evolution of Human Values with Ian Morris

Ian Morris, Stanford Alumni

Are democracy and gender equality always good? Are violence and wealth inequality always bad? This presentation will dive into what drives changes in human values and what we as a society consider good or evil.

The Mountain People

Colin Turnbull

The story of the IK tribe of northeastern Uganda is a classic study of how a society’s concept of fairness and justice can quickly devolve when its people are cut off from their accustomed means of livelihood and forced to compete for their very survival.

The Measure of Civilization

Ian Morris

For those who wish to explore both the evidence and the statistical methods used in Why the West Rules – for Now and the Social Development Index, Morris published this detailed sequel. An extended technical appendix, the book is largely concerned with method, but has been referred to as a treasure trove of information about social development.