Neolithic Era:

Death and Transcendence

Statues from Ayn Ghazal, Jordan

In the Neolithic period, shamans became the specialists in transcendence. The stability of the community rested on their ability to engage the whole group by connecting it to the spirit world. How did they do this?

As Robert Wright points out his book The Evolution of God, over time a ruling partnership of sorts developed between shamans and tribal chiefs to intercede with the other world, and to control and organize the population. While still imbued with the strategies and phases of their traditional practice, shamans now began to adapt these, when possible, to accommodate this new role. They became the specialists in transcendence and the stability of the community rested on their ability to engage the whole group by connecting it to the spirit world.

How would they do this?

Their insight was to involve those who had gone before, with whom the group already had a strong emotional connection. Shamans in collaboration with the chiefs or elders of the group, and with an enormous commitment from the group, now called upon their dead to intercede with the spirit world on their behalf for their approbation and the subsequent success of all. For the period we know as Neolithic, the dead would be prominent in our search for meaning.

David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce examine this aspect in their book Inside the Neolithic Mind. “…the importance of the dead was that they move through the cosmos. Like the sun, they were a dynamic element, a mediating factor between levels of the cosmos. Therein lay their power and the power of those who managed to associate themselves with the dead and their cosmological travels: the dead placed the living – or rather some of the living – at the point of transition, the vortex, and thus in positions of power. The seers probably said that they were taking care of the dead, but it was actually the dead who were taking care of the seers.”

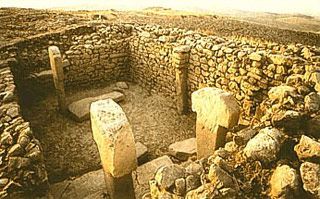

Graves were discovered at Nevali Çori, and the late German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt, who with his team led the excavations at Göbekli Tepe for over fifteen years, was reasonably confident that burials lie somewhere in the earliest layers. His team found fragments of human bone in the layers of dirt that filled the complex, which led him to suspect the pillars represent human beings and that the cult practices at this site may initially have focused on some sort of ancestor worship.

Perhaps this functioned as the burial ground for the priesthood. It is the custom of shamanic societies to bury their elders and shamans in ground already made holy or sacred by the ritual practices that had previously gone on there, even led at one time by the person buried there.

At Tell Qaramel in northern Syria, one of the oldest known settlements (ca. 11,000–9650 BCE), skulls were found either in groups or alone, some plastered with clay to recreate the face, which was then painted skin-color and placed in a specific area, presumably for veneration or at least remembrance. Bodies were buried in the flex in-utero position, perhaps ready to be born anew in the spirit world. Children who died young were buried intact, which leads scholars to think that adult brains may well have been eaten at death as a way to pass on the deceased’s essential qualities to the living.

Jericho was originally founded by sedentary foragers/collectors in the Natufian Period some 12,800–10,500 years ago. Excavations revealed sometimes up to nine human skulls buried beneath the floor of these Neolithic houses. Their faces were modeled in plaster often with inset cowrie shells for eyes and painted representations of hair and other facial features. Plastered skulls were also found at other sites, for example in Kfar HaHoresh in the Nazareth Hills of Lower Galilee in Israel and in Beidha, near Petra in Jordan.

The Long Transition from Hunter-Gatherer to Farmer

Göbekli Tepe and other recently excavated sites in the Near East led scholars to question the long-standing idea of the Neolithic Revolution, invented by V. Gordon Childe in the 1920s, that agriculture, stimulated by population growth, gave rise to organized religion. Scholars surmised that the earliest monumental architecture was possible only after agriculture provided Neolithic people with food surpluses, freeing them from a constant focus on day-to-day survival. Instead, more recent evidence from the site leads us to conclude that the transition from Paleolithic man to Neolithic man took thousands of years longer than we thought. And the site was never exclusively used for ritual purposes.

Recent findings by Lee Clare and his team reveal evidence of corbelled roofing, proving that these structures originally supported domed roofs. In 2015 the team discovered dwellings and a domestic activity zone in the northwestern part of the site. These recent findings led to a reinterpretation of Göbekli Tepe as a settlement rather than a purely ritual site, as initially suggested by the late Klaus Schmidt. From the very beginning people appear to have settled there, initially perhaps temporarily, moving along with food sources, but from the mid-ninth millennium BCE a large settlement flourished there, as testified by the many rectilinear residential spaces in the main excavation area. Clare states, however, that “it is still essential to emphasize the temporal overlap of the domestic spaces on the slopes with the later phases of the long-lived special buildings in the lower-lying basins.”

There is no evidence of domesticated animals or crops, so the hypothesis that states that Göbekli Tepe marks a transition to agriculture must be revised. Thousands of animal bones and have been found at the site, but these are all wild, leaving scholars to conclude without doubt that the people who built Göbekli Tepe were hunter-gatherers, not farmers or herders.

The inundation of the special “temple” buildings (A–D) in the southeastern part of the site by slope slides was perhaps not the end of the occupation sequence; nevertheless, it marked a crucial turning point, ultimately leading to the abandonment of the settlement.

Clare’s findings suggest that to understand this period, we must look more closely at the timeline and consider the dramatic adaptive changes our ancestors had to make before a comprehensive transition to agriculture became possible. It took thousands of years of societal development until, right as the occupation of Göbekli Tepe is ending, we have the first evidence of domesticated animals and plants—of agriculture.

Ian Hodder, an archeologist working at Çatalhöyük, correctly claims that “Communal ceremonies come first. That pulls people together.” While there is no direct evidence of agriculture during the period in which Göbekli Tepe was built, the main ritual monolithic buildings indicate that the urge to transcend the boundaries of normal everyday consciousness, in search of the meaning and purpose of existence, was of primary concern.

We’re able now to reflect that the transition from hunter-gatherer to forester, and finally to agriculture took many, many thousands of years. This is hardly surprising when we recall that before this time and for approximately 25,000 years—a period twelve times longer than the Common Era—homo sapiens sapiens moved in bands of an average of 25–30 people and predominantly relied on cave and rock shelters. This Neolithic period presented enormous challenges.

External Stories and Videos

Göbekli Tepe

BBC

How did the first farmers sustain a large community and build Göbekli Tepe 12,000 years ago?

History of Stonehenge

English Heritage

Explore the history of this prehistoric monument with interactive maps of all phases of development.

Unveiling an Underground Prehistoric Cemetery

Google Arts and Culture

A look inside Malta’s World Heritage Site, the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum.