Featured Book

Rescuing the Planet

Protecting Half the Land to Heal the Earth

Tony Hiss

“Everything is impossible until it’s done.” – Nelson Mandela

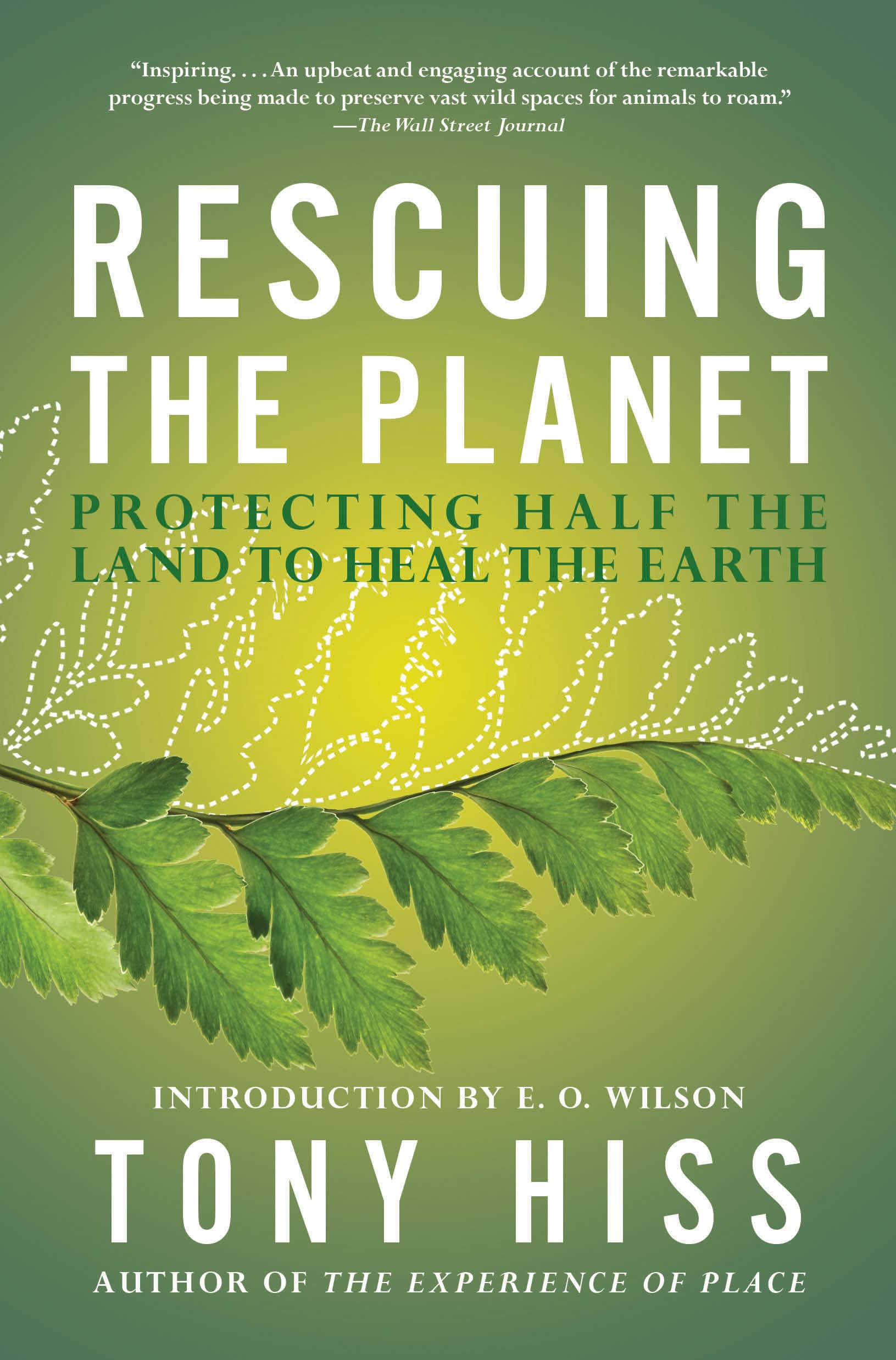

A surprising and genuine optimism about the Earth’s future emerges from the pages of Rescuing the Planet, by Tony Hiss, former staff writer for The New Yorker. Hiss finds this hope in otherwise ordinary people who are forging new protections for magnificent and vital expanses of wilderness. Often unaware of each other’s actions, these environmental protectors are bringing reality to the dream of “Half-Earth,” Hiss’s term for the ambition of renowned biologist Edward Wilson to protect half the Earth’s land and sea for nature by the year 2050.

Wilson understood that the extinction event now taking place might become as far-reaching as the one that killed the dinosaurs. He calculated that the only way to prevent this is to permanently protect half of our planet for nature by the year 2050 – in other words, “Half Earth.” When interviewing Wilson, Hiss wondered if achieving Half-Earth is even possible, and so he set out across North America to see for himself. Rescuing the Planet touches on the science of this conservation movement, but it focuses on the individuals who are making a true difference in saving our world.

The Future

Six Drivers of Global Change

Al Gore

No period in global history resembles what humanity is about to experience. Explore the key global forces converging to create the complexity of change, our crisis of confidence in facing the options, and how we can take charge of our destiny.

Our Choice

A Plan to Solve the Climate Crisis

Al Gore

We clearly have the tools to solve the climate crisis. The only thing missing is collective will. We must understand the science of climate change and the ways we can better generate and use energy.

The Big Ratchet

How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis

Ruth DeFries

Human history can be viewed as a repeating spiral of ingenuity—ratchet (technological breakthrough), hatchet (resulting natural disaster), and pivot (inventing new solutions). Whether we can pivot effectively from the last Big Ratchet remains to be seen.

The Sixth Extinction

An Unnatural History

Elizabeth Kolbert

With all of Earth’s five mass extinctions, the climate changed faster than any species could adapt. The current extinction has the same random and rapid properties, but it’s unique in that it’s caused entirely by the actions of a single species—humans.

Natural Capitalism

Creating the Next Industrial Revolution

Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins & L. Hunter Lovins

A new definition of capitalism that fully values natural and human resources may hold the keys to a sustainable future.

Foragers, Farmers, and Fossil Fuels

Ian Morris

Human social development, says Morris, is constantly generated by environmental and social factors. The amount of energy that can be extracted from the environment through technology defines the social possibilities, and thus influences the attitudes and world view of each epoch.

In the series: A Sustainable Planet

- Our Finite Planet

- Our Climate Crisis—and What We Can Do About It

- The Rocky Road to a Sustainable Future

- Our Looming Global Water Crisis

- Our Plastic Earth

- The Future: Six Drivers of Global Change

- Our Choice: A Plan to Solve the Climate Crisis

- The Big Ratchet

- The Sixth Extinction

- Natural Capitalism

- Foragers, Farmers, and Fossil Fuels

Related articles:

Further Reading »

Further Reading >

External Stories and Videos

Down to Earth

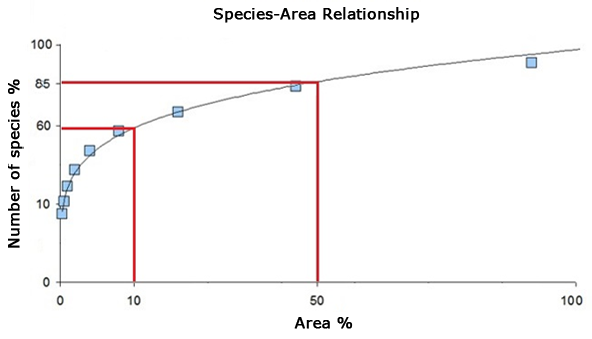

The Pangasananan territory of the Philippines has abundant wildlife because it has been occupied and conserved for centuries by the Manobo people. This area is one of many Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs) around the world where conservation practices of indigenous peoples have benefitted all of us by conserving an estimated total of 21 percent of all land on earth.

Canadian Caribou Make a Comeback

Priya Shukla, Forbes

In another example of indigenous stewardship of critical wildlife habitat, First Nation communities in Canada have sparked a revival of the caribou population of British Columbia.

Watch: Coyote and Badger

Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST) / Pathways for Wildlife

We know from scientific studies and Native American records that coyotes and badgers have been known to hunt together. But this is the first documentation (that we know of) where a coyote and badger use a human-made structure to travel together safely.

Watch: Connectivity Conservation

Center for Large Landscape Conservation

Learn how all of us can help avoid landscape fragmentation, where roads and other human activities divide habitat into isolated patches and make it difficult for wildlife to thrive.

Watch: Why Wildlife Corridors Matter

Center for Large Landscape Conservation

This video illustrates the importance of large landscape conservation—why connected natural areas are so critical—not only for wildlife, but for all of us.

Watch: Restoring Landscapes for Life

Cambridge Conservation Initiative

Several recent restoration projects on both land and sea provide cause for real optimism and demonstrate how we can make ecosystems more resilient and enable species to return to their natural habitats.

Watch: Working Lands, a Story of Bears and Ranching

Future West

This video illustrates how ranchers in the western U.S.A manage their land, including its wildlife, and see why working ranches are critical to habitat connectivity and wildlife preservation.