Neolithic Era:

Britain’s Megalith Building Boom

Stonehenge, Wikipedia

In Britain, about 1,300 Neolithic mega-sites appear to have been built within little more than a century.

While Stonehenge is definitely the most famous stone circle in the British Isles, recent discoveries reveal that about 4,500 years ago as the Neolithic era reached its end, as many as 1,300 Neolithic megalithic sites dominated the British landscape. And many of them, whether huge stone circles, colossal timber structures, earthworks, or impressive avenues of standing stone, appear to have been built within little more than a century. Given that these people used only antler picks and stone tools to move their forests’ biggest trees, huge stones and tons of earth—often over many miles—this is an astonishing feat.

To give an idea of the huge wooden structures they created, Mount Pleasant is an area bordered by a henge three-quarters of a mile in circumference that contained a circle of 1,600 towering ancient oak posts, each some five or six feet thick and weighing more than 17 tons. These were spaced closely together, forming a huge fence, which suggests access inside the ring was carefully controlled.

There’s even a huge artificial chalk mound that holds no human remains, called Silbury Hill. It is thought to have been created to promote or celebrate the communal act of building, which would make sense given that people apparently traveled long distances to take part in these constructions. The mound is part of a complex of Neolithic megalith monuments around Avebury, a henge containing a large outer stone circle with two separate smaller stone circles inside the center. The complex includes a series of what once were huge wooden enclosures—one over 650 feet across—located in a place known as West Kennet about 20 miles from Stonehenge.

Stonehenge: The Power of Coincidence

Evidence suggests that hunter-gatherers first built on the megalithic site that would become known as Stonehenge as early as ca. 8,000 BCE. Three or four large Mesolithic postholes, about 2.5 feet in diameter, appear to have been erected in an east-west alignment, presumably for ritual purposes. But why there?

New findings by archeologist Professor Michael Parker Pearson and his team at the Stonehenge Riverside Project seem to have found the answer. When a trench was opened up across the final part of what is now known as the Avenue, a grooved pathway was discovered between two parallel banks about 40 feet apart with internal ditches. It begins at the entrance to the structure and terminates at what used to be another stone circle known as Bluestonehenge by the River Avon.

The Avenue was caused by peri-glacial erosion, at the end of the last Ice Age. It was 0.3 miles long and about 98 feet wide and coincidentally marked the solstice sunrise line – the longest and shortest days, so vital to Neolithic farmers. But how could our ancestors have known the cause? As is still often the case for modern man, a coincidence was perceived as a sign from the heavens.

“When we stumbled across this extraordinary natural arrangement of the sun’s path being marked in the land, we realized that prehistoric people selected this place to build Stonehenge because of its pre-ordained significance. … Perhaps they saw this place as the center of the world.” said Pearson.

About 5,000 years ago Stonehenge was very different from what we see today. It consisted of an outer bank, ditch, inner bank and a huge circle of 56 erect bluestone blocks, each weighing about four tons. A recent examination of the stones, the pits in which they were erected, and about 50,000 bone pieces collected from under the pits, revealed surprises. Over a period of 500 years the dead were cremated and their bones buried under these bluestones. Occipital bones vary in thickness (they are thicker in men than in women), and from these we know that this was a cemetery for both males and females, including five children. Parker Pearson and his team feel that the dead were likely some sort of elite dynasty, or family of aristocrats that ruled over Stonehenge for five centuries, between 3000 and 2500 BCE.

Song of Stonehenge: Experimental Multimedia Archaeology

This is a short film, exploring a 3D model of Stonehenge. It was made by Rupert Till, Ertu Unver and Andrew Taylor of the University of Huddersfield. It features a digital model of Stonehenge made using photographic scanning technology, linked to digital audio models of the site, so that it sounds as well as looks accurate. The instruments you hear are all experimental archaeological reconstructions of archaeological finds, of clay TRB drums from Europe, the Wilsford Flute, bone horns, bullroarers, all with the acoustic impulse response of Stonehenge at various points approaching and inside the site, added in.

The film begins moving along the Avenue, the ritual approach to Stonehenge. It is dusk on the 21st of December, as the stones slowly approach over the horizon. You slow as you approach the Heel Stone. As you pass this you begin to hear the echoes and reverberation present in the central stone circle. When you get to the center your spirit leaves your body and flies up and around the space.

The four-ton bluestones, which take on a vaguely gray-blue color when wet, are only to be found in Preseli Hills in West Wales about 180 miles away. More recently, the construction of a bluestone monument circle at Waun Mawn in the Preseli Hills has been discovered. It appears to have been abandoned before completion sometime after 3000 BCE, but has intriguing similarities to Stonehenge. Empty stoneholes suggest that some bluestones were removed from this site. Could they possibly have been taken to Stonehenge as part of a migration of Welsh Neolithic culture towards the east?

Some scholars have suggested that the stones were brought over because of a belief in their healing powers; bluestones in Wales were tested and found to have a sonic property—they ring when they are struck and have a number of tones, which may have contributed to the reason. Others think it is more likely that the stones represented the identity of these immigrants, saying in effect, “We are the descendants of people from over there. A thousand years ago we came from over there and we are here now. We and our ancestors belong here and on this land.”

“You might image that they are an embodiment of the specific dead people in whose honor they are being raised, or of the people who raised them. The sense is that the stones actually are people,” says Professor Julian Thomas of the University of Manchester.

In about 2500 BCE, Stonehenge underwent major rebuilding work and the bluestones from Bluestonehenge appear to have been incorporated into its expansion. Five sarsen trilithos (pairs of uprights with a lintel across each) were erected within a gigantic circle composed of 30 huge, squarely shaped sarsen stones, each joined by lintels fitted together with mortice and tenon joints. The creation of such sophisticated joints and perfect geometry is unique for this period in history and unique to Britain in plan and design. The structure was very likely roofed, though no details remain. Some of the bluestones were later removed, leaving the final setting, the remains of which can be seen today.

Stonehenge stood in a key position on the axis of the sun’s solstice in what Pearson and his team discovered was a ritual landscape. About two miles to the north of the stone circle is what is known as the cursus – an earthwork enclosure that stretches over a mile and a half. Although created about 500 years before, the enclosure seems to have played an important role at the time of Stonehenge: marking the boundary of the sacred landscape of the dead and the land for the living.

Beyond the cursus further north is Durrington Walls, a henge 20 times the size of Stonehenge surrounded by a ditch 18 feet deep and 30 feet wide that stretches for a mile around the perimeter. The apparent reason for the location of Durrington Walls, its avenue and timber circles, is that nature had created geophysical features that, just like at Stonehenge, are naturally astronomically aligned. Pearson and his team excavated there and found at least two other ceremonial circles. The better preserved “Southern Circle” resembled Stonehenge but was built out of wood. Antler picks used for digging and left near the site indicate that it was built over the same period.

Since wood doesn’t last forever, Pearson and team believe the ceremonial circle at Durrington Walls represented life for these early ancestors, while the indestructible Stonehenge represented eternity, and was therefore for the ancestors.

The wooden circle aligns to the sun’s setting in the west—here remains of excessive feasting have been found: half-eaten animal bones and waste covered the site, leading archeologists to conclude that significant ceremonies took place such as marriage rites with feasting, dancing and celebrations of life and fertility. They would be back there nine months later when a new generation would be born, and both the human and animal cycle be renewed.

Outside this henge Pearson’s team found an area that contained well over 1,000 wooden houses, 14- x 14- foot square, each with a central fireplace. These findings and the fact that avenues connect Stonehenge and Durrington Walls to the river Avon have led to the theory that the river linked the “domain of the living”—marked by the timber circles and houses upstream at the Neolithic village—with the “domain of the dead” marked by the stone circle of Stonehenge.

How and Why Did They Do It?

Scholars think that Stonehenge may well have been expanded as a reaction to a long period of violent conflict between east and west Britain, with the stones from southern England and west Wales, symbolizing different communities. As Pearson pointed out, building Stonehenge required everyone “to pull together” in “an act of unification.”

In common with so many Neolithic peoples, for the thousands who participated in the rituals of Stonehenge, tremendous physical effort and struggle seem to have been part of their religious duty, “it’s the labour that counts,” says Pearson. “We are looking at an age when devotion was really important. This is just one of a whole series of spectacular earth-moving and stone-moving events that Neolithic people were not just capable of, they wanted to do it. I think that is the missing part of the equation: that is, if you have the will you can move mountains. And they clearly did.”

The much larger super-hard “sarsen” stones came from Marlborough Downs over 19 miles away. Each stone weighed more than 25 tons. About 50 sarsen stones remain, though there are thought to have originally been many more. Each stone is shaped and joined, crafted like wood, requiring expert stoneworkers and exceptional engineers. Every stone’s rough surfaces had to be smoothed with stone hammers, though only a few have carvings, which look like daggers and axes. The sarsens varied in length, so they needed to be buried at different lengths to make the top level for a roof. They had to be hauled up a ramp to a pivot point made of tree trunks and finally pulled vertical.

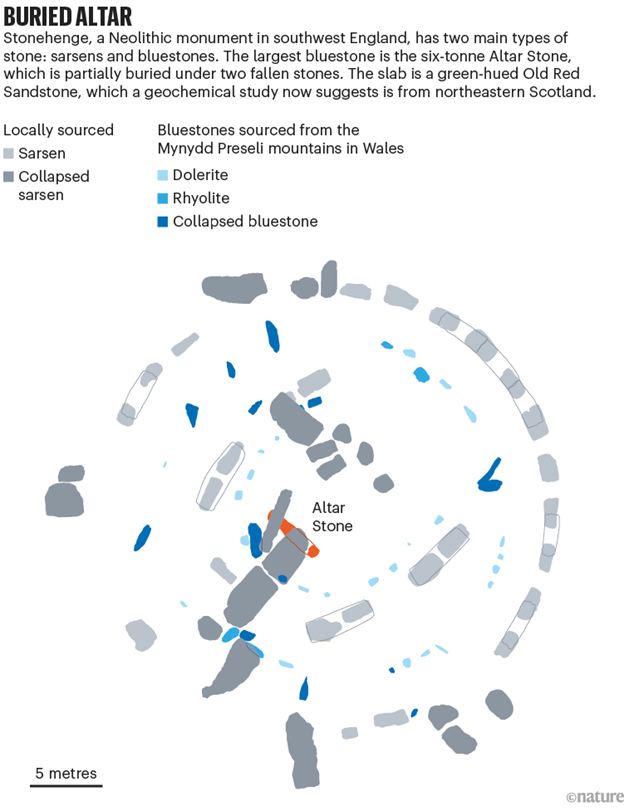

Stonehenge’s Enigmatic Altar Stone Was Hauled 800 Kilometres from Scotland

The origins of the stones that make up Stonehenge can give us insights into the surprising connectivity of Neolithic society in Britain in about 4300 to 2000 BCE. The megalithic monument is composed of two types of stones: the larger sarsens, which, as we mentioned above, are believed to have been transported from Marlborough Downs, about 19 miles north of the site, and the smaller bluestones, traditionally thought to have come from the Preseli Hills in Wales, some 240 kilometers away.

A recent article published in Nature in 2024 reported that a geochemical analysis has disclosed the age and minerals of the Altar Stone, a partially buried slab of sandstone which lies flat at the center of the Stonehenge. It revealed that this six-tonne, five-metre–long rectangular slab originated not from Wales, as previously thought, but from the Orcadian Basin in the far north of Scotland.

For this to happen the stone had to have been transported by Neolithic mariners 800 kilometers by sea. It implies that communication networks between Neolithic societies in Britain was far more extensive 5,000 years ago than previously supposed. Far from being isolated or primitive, the builders of Stonehenge shared cultural ideas and were likely engaged in long-distance trade, connecting distant regions of Britain in ways that we are only just beginning to understand.

It’s estimated that up to 4,000 people met together in Stonehenge to celebrate the solstice and pay respects to the ancestors and gods. Tooth enamel isotope analysis of animal teeth reveal that people came from as far away as Scotland, even perhaps the Orkney Islands at the other end of the country from Stonehenge. It meant travelling with your family and animals by foot and boat for 700 miles; a journey that would have taken the best part of a month.

Trevor Cox, Professor of Acoustic Engineering, finds that the Neolithic builders of Stonehenge created a stone circle that results in a highly reverberant sound field within it despite the fact that the stones had no roof. The sonic environment would have been akin to sounds in the Paleolithic caves, the Neolithic mound passages, or those found later in the cathedrals built in medieval times. The echo-chamber effect on any music or chanting within the stone circle at Stonehenge would have strongly affected the participants in any human ceremonies performed in that space.

This huge scale of ritual and festivities ended when a fundamental shift in the beliefs of society took place. The large communal labor force was no longer required; the dead were no longer cremated but were now individually buried in mounds with their valued possessions.

Until then stone was the most precious commodity they had. It had helped them survive for thousands of years. But from about 2500 BCE the world started to change. Visitors arriving from mainland Europe brought with them a new technology and a new culture.

The Amesbury Archer: The Dawn of Metallurgy

In a burial site three miles from Stonehenge, archeologists found a 4,500-year–old skeleton, buried with over 100 artifacts. This was no ordinary man. The Amesbury archer died between 2470 and 2280 BCE. Analysis of the archer’s tooth enamel suggests he may have originated as far away from Britain as the foothills of the Alps.

Previously excavated European burial sites from this period revealed skeletons buried along with one or two objects, ten maybe at most, but over 100 artifacts made this the richest grave so far excavated in Europe. The objects included a stone belt buckle, tiny copper knives, arrowheads and small copper daggers; and two identical gold ornamental hair clasps—among the earliest gold objects to be found in Britain.

These strangers could take a rock and melt it, then turn it into something entirely new and shining like the sun. To the people of Stonehenge they must at first have seemed like magicians. As it reaches its peak, this new metallurgy changes nearly everything—personal wealth and status becomes paramount. The age of massive stone megalith monuments has come to an end, metal makes people think about new ways of interpreting the same age-old questions—who are we and where are we going?

External Stories and Videos

Drought and Drone Reveal ‘Once-in-a-Lifetime’ Signs of Ancient Henge in Ireland

Daniel Victor, New York Times

It took an unusually brutal drought for signs of a 5,000-year-old monument to suddenly appear in an Irish field, as if they had been written into the landscape in invisible ink.

Watch: Göbekli Tepe

BBC

How did the first farmers sustain a large community and build Göbekli Tepe 12,000 years ago?

History of Stonehenge

English Heritage

Explore the history of this prehistoric monument with interactive maps of all phases of development.

How did they do it?

Sarah Knapton, The Telegraph

Just how did prehistoric Britons manage to transport the huge bluestones of Stonehenge some 140 miles from the Preseli Mountains in Wales to their final home on Salisbury Plain? It may have been easier than we thought.

Watch: Secrets of Stonehenge

National Geographic

Many secrets remain surrounding the creation of Stonehenge. Archaeologists try to unravel the mystery.

Unveiling an Underground Prehistoric Cemetery

Google Arts and Culture

A look inside Malta’s World Heritage Site, the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum.