Aegean Neolithic and Bronze Age Civilizations:

Minoa—Europe’s First Civilization ca 2000–1400 BCE

Crete is one of the largest islands in the Mediterranean Sea, situated in its eastern center at the crossroads of Africa, Asia, and Europe. It was the hub of a cosmopolitan world that included Egypt, the Levant, Anatolia, and the Greek mainland – all sharing ideas, the evidence of which can be seen in their architecture, art and symbols.

The earliest evidence of human habitation on the island dates from around the 7th millennium BCE, most likely when Neolithic populations migrated to Europe from the Middle East, Turkey, and the Greek mainland.

The lower levels of the Knossos palace complex provided some of the earliest evidence to date of human activity on the island from around 6100–5700 BCE. The skeletons of seven children were found buried in shallow tombs dug under the dwelling floors. Three of the children were newborns while the others were all under seven years old, all lying in fetal position in tombs empty of offerings or other objects.

Communities of several families are thought to have lived in close quarters with each other with their animals and crops, and they appear to have spent most of their time outside. Excavations found one- or two-room clay houses, with flat roofs made of branches and clay.

Around 4000–3000 BCE, the island’s population increased dramatically, suggesting an immigration to the island. As time went on dwellings grew more substantial, with one particularly large one, indicating perhaps some sort of community center, which may also have been the home of the chief or priest. By the end of the Neolithic (ca 2800 BCE), the Knossos settlement is thought to have reached 2,000 inhabitants, and human activity had spread throughout the island.

Single cave burials of a number of people have been found in the north and the east of the island. Neolithic settlements such as at Myrtos and Mochlos have been found dated from about 2600 BCE, with architectural remains consisting mostly of circular domed tombs, which were used by entire families or clans.

A Bronze Age Success Story

The Minoans were the first Europeans to construct paved cobblestone roads. Their society included highly skilled artisans and engineers, and they were excellent ship builders and sailors. Their maritime empire included Spain and parts of modern-day Turkey, the Middle East, and Egypt.

As far as we know, they were the first Europeans to use a written language. They wrote in a hieroglyphic script known as Linear A, which has as yet to be deciphered, so like the Indus Valley civilization, we can only deduce what their lives were like from the architecture, art and objects they left behind.

But they left a wealth of evidence: uniquely creative palaces, frescoes, pottery and seals which indicate a prosperous, peaceful society, whose people lived in intimate harmony with nature. But, as Dr. Nanno Marinatos says, “At the same time, there is no shrinking from realism and violence. You have the ideal and the reality of life juxtaposed, and it is just a beautiful way of looking at life.” It appears to be one where women enjoyed equal status with men, if not higher.

Trade and Influence

Connection and trade with the outside world was imperative to the Minoans’ ability to initiate and sustain their successful Bronze Age civilization, which emerged around 2000 BCE and lasted for about six centuries.

Five thousand years ago, Minoan oarsmen rowed boats of cypress wood wrapped in animal skin from ports such as Mochlos on the east coast to Egypt, the Middle East, Cyprus, and the Greek mainland. They were the first sea power in the Aegean and had uncontested maritime control from about 2100–1600 BCE. Trade winds worked to the advantage of their large fleet, which was useful for both trade and defense. It is likely that they used their naval power as defense, strategically placing vessels among the islands nearby to protect their isolated position. Their palace citadels had no fortified walls: the walls that have been excavated appear not to go completely around the palace site, for example, at Knossos. However, the labyrinthine layout of the palaces and even of smaller villas found of the same period, may well have provided the protection they needed. When a single door might close off an entire wing or seven or more doorways open up from a single corridor, the outsider would definitely be confused and wonder if, once in, would he find his way out?

(Right) Kamares banquet vessel with decorative lilies, Phaistos from 1800–1700 BCE.

Raw materials were imported, especially metals like gold and silver; or copper and tin – for bronze – the making of which they most likely learned from the Middle East. Exports were of wood and luxury items: delicate pottery and ceramics such as the eggshell-thin Kamares ware, perfumed oils, wine, textiles, jewelry, fine crafts and the purple dye Minoans acquired from farming murex mollusks. Known as “royal purple,” this was the most valued dye of the ancient world, used internationally for the garments of high society. The Minoans are said to have been first to develop the purple dye industry, some time before 1750 BCE.

Trade obviously enabled the cross-pollination of ideas, but additionally, as civilizations developed, artists and craftsmen were lent out to other cities and states by rulers as a mark of generosity and a display of their own prestige. Minoan metal workers were renowned and many artisans worked abroad in mainland Greece, the Aegean islands and elsewhere. The Mycenaeans learned the art of inlaying bronze with gold from the Minoans.

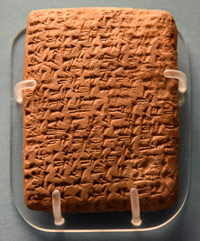

The Egyptian Amarna (Echnaton) letters are the earliest written evidence of a network of diplomatic and trade relations between the major powers around this period. Written on clay tablets in cuneiform script in what seems to have been an international language – a kind of Akkadian – the correspondents include the leaders of Egypt, Babylon, Syria, Mitanni, the Hittites, Canaan Alaschia (Cyprus), Mycenae and Crete.

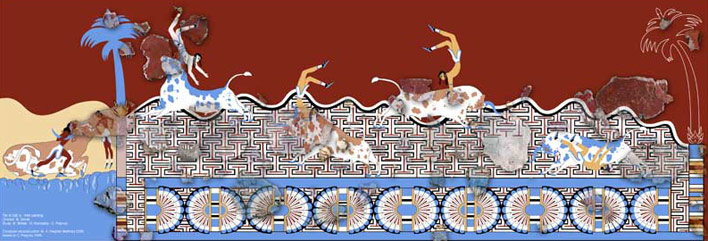

We know that Minoans travelled up the river Nile to the Valley of the Kings. Frescoes, undoubtedly Minoan, have been found, for example, in the tomb of Thutmose III (1479–1425 BCE). As Dr. Alicia Meza says in Research in Anthropological Topics, “There is plenty of evidence for the ancient Egyptian-Minoan interaction dating as far back as prehistory times.” She goes on to say that in later times “Knossos sent delegations with rich goods to present to the Egyptian king in 1300 BCE.… Representations on the walls of the tombs of high officials show the Keftiu bringing their presents during the Durbas of the Egyptian kings.” The now famous fresco paintings in the tombs of Rekhmire, who served Thutmose II and Amenhotep II as vizer, are what we recognize as Minoan, as are those in the palace of Thutmose III reproduced here. Minoans are described as “the Keftiu,” which must have been their real name. They are also referred to in the Old Testament as “the Caphtor.”

The Minoans revised, redesigned and embellished artifacts wherever they could. Their frescoes depict people whose faces are always in profile reminiscent of Egyptian art, but each one is imbued with a natural grace and fluidity, often interacting with the natural world, or depicting elements of that world in a way that is so elegantly stylized, so joyous, it can take your breath away.