Aegean Neolithic and Bronze Age Civilizations:

Minoa “Palaces” and Religious Beliefs

“And on the shield…

the famous god whose legs are bent created a dancing area, like that once made by Daedalus in monumental Cnossos for Ariadne with the lovely braids.

Handsome young men and pretty teenage girls, worth many oxen as their marriage price, were dancing, holding one another’s hands.”

—Homer, The Iliad, ca 8th century BCE

Portrait by Sir William B. Richmond, 1907

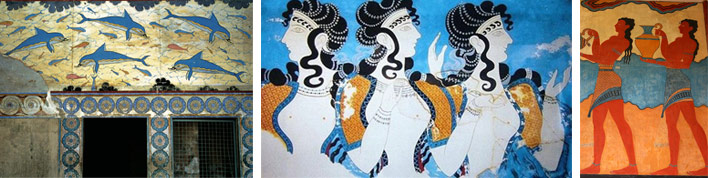

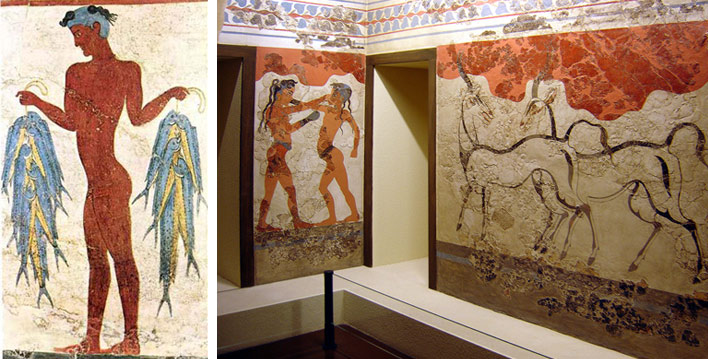

In 1900, the famed archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans provided the first evidence of an extraordinary civilization. He named it Minoa, after the legendary King Minos, son of Zeus. Using wet pigments requiring quick execution, the Minoans painted walls with great skill and fluid brush strokes, which in their hands accentuated the movement of life in their world, where nature and man were inextricably intertwined. As was typical with pre-Axial peoples, their world was suffused with the divine and charged with religious meaning. They worshipped trees, sacred stones and springs, and their rituals included animal sacrifices. There is some evidence—at the sanctuary at Anemospilia (Archanes) some seven kilometers south of Knossos—that indicates human sacrifice as well.

Called “palaces” by Evans, it is more likely that these monumental buildings of Middle Bronze Age Crete (ca 1900 BCE) functioned as ceremonial and religious centers, storehouses and meeting places: the hub of community life and likely the domicile of their leaders, whether priests, priestesses, kings or queens. As with the Knossos site, they were generally erected over Late Neolithic and Pre-palatial tombs—tombs that may well for the first time have symbolized ownership and the authority of one family or clan over an area.

In all likelihood, their descendants maintained their power over the “palaces.” They may have been inspired to erect these imposing, monumental structures after trade or diplomatic visits to the Near East or Egypt—suggestions have been made that the many labyrinthine rooms reflect those they may have seen in the Hawara Labyrinth Egypt Complex, mentioned by Heroditus.

These large and complex structures appear to have been built around the same period as the emergence and flourishing of writing, mass-produced wheel-made pottery, and crafts—aspects of society only possible once an agricultural surplus allowed people to take up full-time occupations other than farming. The organization of materials and labor, the planning and labor-intensive craftsmanship that had to have been involved implies a socially complex society that was almost certainly hierarchical.

Minoan palaces were three and four stories high, with large staircases, light wells, water and drainage systems, flush toilets, hot water heaters and hinged doors.

So far, four palaces have been excavated: Knossos (Cnossos), Phaistos, Malia and Kato Zakros, all on the east of the island. But the number of possible “palaces” keeps growing—including Khania (Chania), Petras, and Galatas, and perhaps Palaikastro and Arkhanes.

The “palace” of Knossos was undoubtedly the most important ceremonial, trade and political center of the Minoan civilization. It was 3.861 square miles in area, and three and four stories high, with about 1,500 interconnecting rooms, many below ground. Levels were supported by red columns, white floors and white walls, with beautiful frescoes that scholars agree must have held symbolic meanings for the inhabitants. There are seven or eight separate entrances to the building, including a huge main entrance, that lead to a maze of workrooms, living spaces, theater spaces, anteroom, cult rooms and storerooms, and what Evans described as “lustral basins” thought to have been used for ritual initiation, perhaps a purification ceremony of some kind involving a symbolic descent into the earth. Since their depth is about two meters, and some appear to be in public places such as opposite the stone seat or “throne” at Knossos, it is unlikely that they were used for regular bathing. A central court the size of four tennis courts is situated at the building’s heart and thought to be a space for religious rituals.

Close to the palaces are much smaller groups of buildings to house members of the palace elite. They often exhibit the same artistic and architectural motifs as the palaces, though on a less magnificent scale. Palaces were generally situated in or near towns and cities where all the workers lived, as well as the traders and crews who manned the Minoa ships. The city of Knossos, adjacent to the great royal palace, was one of the largest urban centers anywhere in the ancient world.

By about 2200 BCE the Minoans were in control of the Aegean islands, not through violence, but through trade. A most perfect example of recognizably Minoan culture is Akrotiri on Thera (modern Santorini). Ash from the infamous volcanic eruption on Thera in 1628 BCE covered the entire settlement in volcanic ash, preserving the city, its pottery and art for three and a half thousand years, until it was discovered by Spyridon Marinatos in 1967.

Minoan “palaces” were built on top of hills, positioned towards sacred mountains, where religious rituals were held in cave sanctuaries. In these and in the palace cult rooms, opiates, music and dance lead to trancelike altered states of consciousness as participants connected more deeply with the spirit world.

This three-part informative video on the Minoan culture includes how the record of Minoan religion can be found in its many images.

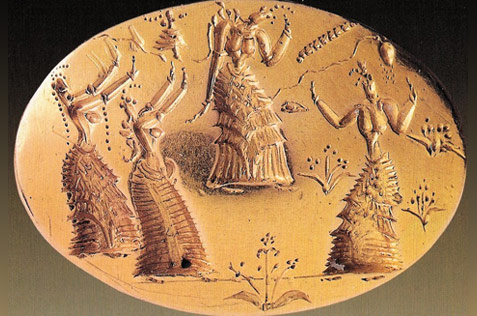

Gold signet rings and stamps depict either women dancing, having ecstatic visions or perhaps goddesses.

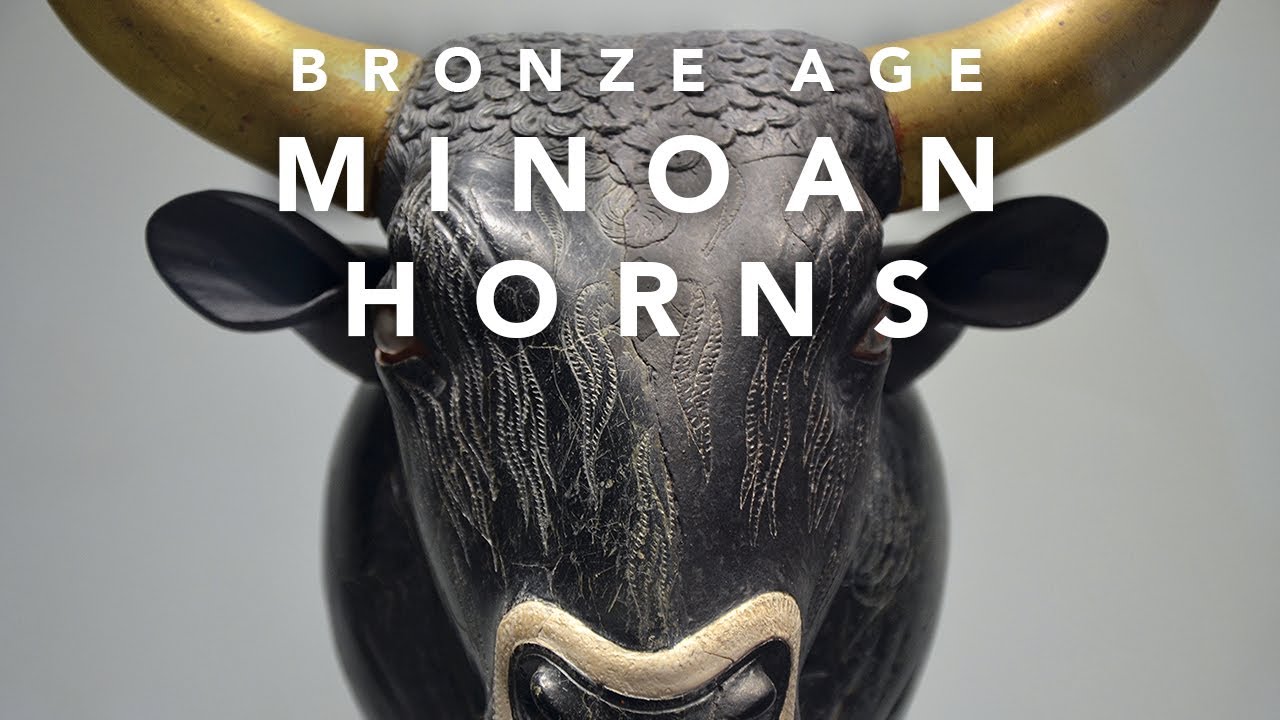

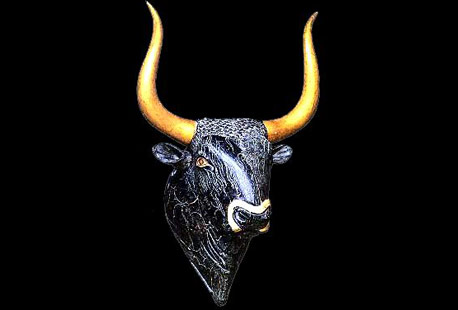

Bull-leaping depicted on golden ring and engraved bull’s head libation vessel.

The major diety appears to be a female goddess, as Dr. Nanno Marinatos states, “Whenever you have a seated figure it is a female—never a male.” Males in the same image appear young, strong, and athletic but smaller, which suggests a mother son relationship—this duality representing both genders. Since the female is flanked by images belonging to an otherworldly landscape, one can infer that she is a goddess rather than a human queen, though in this region of the world during the Bronze Age, the monarchy were often regarded as both political leaders and earthly representatives of the divine. Their awe-inspiring palaces and temples viewed as a central axis within the cosmos.

The ubiquitous bull, whose image was first noted on the Paleolithic cave walls—and later in the ancient rituals and homes of Çatalhöyük, and the seals of the cities of the Indus Valley—appear again in Minoan culture. It’s interesting to note here that these bulls are crossbreed aurochs that stood about six feet high with hooves the size of a man’s head. They most likely signified power and fertility and bull-leaping ceremonies may well have been part of an initiation rite. (Bull-leaping has also been depicted from Hittite Anatolia, the Levant, Bactria and the Indus Valley.) Perhaps, as the historian Bettany Hughes suggests, bull-leaping was a feat that, when achieved, transferred some of the bull’s power to the participants and reminded all Minoans that “The bull charges because that’s what he does, man leaps because he chooses to.”