Neolithic Era:

Neolithic Architecture: Replicating the Cave Experience

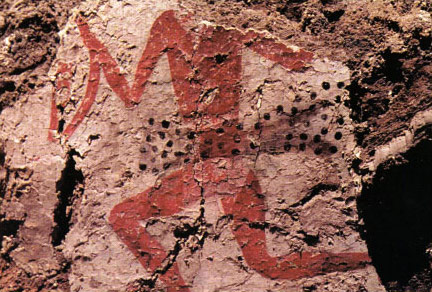

Entrance to Covalanas Cave. Monte Pando, Autonomous Community of Cantabria.

Unlike their prehistoric ancestors, Neolithic shamans no longer had to rely on the natural topography of each cave to fashion their sacred art. Instead, they designed and built structures that repeated the cave experience. In their book Inside the Neolithic Mind, David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce assert that “In doing so they gained greater control over the cosmos and were able to ‘adjust’ beliefs about it to suit social and personal needs.”

The limestone caves in the Taurus Mountains of southern Turkey were thought to have been the initial homes of a hunter-gatherer society who, once the weather improved, moved about two days’ journey away. There, some 3,000 years after the founding of Jericho, they built a Neolithic settlement known as Çatalhöyük. Over the span of 1,000 years people continuously inhabited the site, rebuilding their houses atop one another, creating a mound (“höyük”) some sixty feet high.

Çatalhöyük once accommodated an average of 6,000–8,000 people. Not surprisingly people built homes reminiscent of their caves, creating spaces of symbolic architecture which still reflected their close connection to a three-tiered cosmos and spirit world.

Plaster “bulls’ heads” were found in the walls of Çatalhöyük, or were set in rows on benches in the northern halves of some houses. The bulls’ heads were often decorated.

Honey-combed rectangular houses of mud brick were joined together by common walls, their flat roofs providing walkways and an area where, when weather permitted, much of daily life took place. Access to each home was via a ladder through its ceiling from an open roof-entrance. Once inside, moving between rooms was possible only via small openings 28–30 inches high, so people were obliged to crawl or bend low in order to move deeper into the structure.

According to David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce, “In effect, the roofs of the town created a new land surface, probably, we argue, a replication of the cosmological level on which people lived their daily lives. …descent, limited light and the need to crawl through small openings between chambers are akin to the experience of moving through limestone caves. …The cosmos and its animals were embedded in the house.”

The Ice Age shamans of Altamira or Lascaux used their caves’ natural shapes to create three-dimensional spirit bison or horses that float in and out of cave walls, moving in torchlight with a multitude of man-animal-spirits and animal-spirits. Here in Çatalhöyük, three dimensional forms—bulls’ heads, wild rams’ heads, breast-like shapes and leopards—loom out into the room, creating a focal point, an altar where the act of worship is apparent. Several significant figurines and wall paintings from this site are displayed in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, Turkey.

Çatalhöyük: Transcendence through Death and Rebirth?

Indeed, many of the rooms so far discovered in this architecture are shrines. Their walls are painted with striking imagery: a giant bull surrounded by diminutive human beings, a sprinting figure wearing leopard skin, or vultures with wings expanded and the corpses around them headless. These images were often repeatedly plastered over and recreated in a way that appears to emphasize the act of image making. Perhaps, like their Paleolithic ancestors, these people still saw the creative act as as a way to transcend to the spirit world through the permeable membrane of walls that stood between not only spaces but states of being. The anthropologist Maurice Bloc noted that many of the images are violent and favor powerful animals as if the transition to a new stage or state was experienced as violent but necessary. Other images are of birds that symbolize transmigration, suggesting that through death and rebirth, it was possible to see oneself and others as part of something permanent and life-transcending.

Hodder doesn’t think that Çatalhöyük was a matriarchal society, but notes, “There was a balance of power. If one’s social status was of high importance in Çatalhöyük, the body and head were separated after death. The number of female and male skulls found during the excavations is almost equal.”

Honoring Ancestors

Ancestors were obviously highly valued. Floors inside the dwellings are subdivided into discrete levels or platforms and, like the artificial wall columns, were often painted in symbolic red ochre. As many as sixty skeletons have been found underneath some floors. Bodies were flexed before burial, and often placed in baskets or wrapped in reed mats. Disarticulated bones in some graves suggest that some corpses were left in the open air for a time before the bones were gathered and buried. In some cases, graves were disturbed and the individual’s head removed from the skeleton and subsequently used in ritual. Some skulls were plastered and painted with ochre to recreate human-like faces, a custom also seen in Neolithic sites in Syria and at Neolithic Jericho.

Hodder says in The Leopard’s Tale: Revealing the Mysteries of Çatalhöyük “The ability of the shaman or ritual leader to go beyond death and return gives a special status, and would be especially important in a society in which the ancestors had so much social importance. By going down into a deep room in which the dead were buried, the ritual leaders could travel to the ancestors through the walls, niches and floors.”

External Stories and Videos

Drought and Drone Reveal ‘Once-in-a-Lifetime’ Signs of Ancient Henge in Ireland

Daniel Victor, New York Times

It took an unusually brutal drought for signs of a 5,000-year-old monument to suddenly appear in an Irish field, as if they had been written into the landscape in invisible ink.

Watch: Göbekli Tepe

BBC

How did the first farmers sustain a large community and build Göbekli Tepe 12,000 years ago?

Göbekli Tepe Stone May Record Comet Collision

Michael Irving, New Atlas

New study suggests temple stone may be a record of an apocalyptic comet collision 12,800 years ago that caused the last ice age.

Ancient Architects May Have Been Chasing a Buzz From Sound Waves

The OTS Foundation

“We regard it as almost inevitable that people in the Neolithic past in Malta discovered the acoustic effects of the Hypogeum, and experienced them as extraordinary, strange, perhaps even as weird and “otherworldly.”

History of Stonehenge

English Heritage

Explore the history of this prehistoric monument with interactive maps of all phases of development.

Watch: Secrets of Stonehenge

National Geographic

Many secrets remain surrounding the creation of Stonehenge. Archaeologists try to unravel the mystery.

Unveiling an Underground Prehistoric Cemetery

Google Arts and Culture

A look inside Malta’s World Heritage Site, the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum.