Global Poverty Today

A colonial inspector checks the latex collected by native laborers in 1941 in Cameroon.

Growing global income inequality and the absence of the rule of law underlie most of the social and economic problems in developing countries, including the roadblocks to effective foreign aid.

Knowing more about the history of a region and how that history affects its current situation can help economists understand their target communities, governments and countries and make better decisions regarding aid.

The West has spent $2.3 trillion dollars on foreign aid over the past 50 years, and yet:

- As of 2023, approximately 700 million people (8.5% of the global population) live in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than $2.15 per day. (World Bank)

- When measured by the “societal poverty line,” an income amount based on the median consumption in each country, the number of poor people jumps to 2.1 billion.

- 663 million children worldwide—nearly one in three—are living in poverty.

- 2.2 billion people (1 in 4) do not have access to safe water. (Water.org)

- 750 million people do not have access to electricity. (IEA, 2023)

- 3.5 billion people do not have access to safe sanitation. (Water.org)

- 2.1 billion people are without clean cooking facilities. (IEA 2023)

- 251 million children are out of school. (UNESCO 2024)

Why Was Aid Not More Effective?

Rapid growth of average incomes, particularly in China and India, did reduce extreme poverty so that the number of people living under the extreme poverty line steadily declined from 2 billion in 1990 to approximately 700 million in 2024 (under the updated poverty threshold of $2.15 per day), although the level of societal poverty largely stayed the same.

In sub-Saharan Africa, however, due to population increases and the concentration of the poor in hard-to-reach areas, extreme poverty is on the rise. (The COVID-19 pandemic reversed decades of progress, leading to the first global increase in extreme poverty since 1998.)

A key factor impeding progress has been exponentially increasing income inequality, to the point where the richest 1% now owns more wealth than the rest of the world’s population, diverting resources from the world’s poorest people.

In his book The Tyranny of Experts William Easterly, Professor of Economics at NYU and Co-director of the NYU Development Research Institute, points to other issues. He notes that since 1949 when President Truman announced the first US foreign aid program, the West has been under the illusion that global poverty was a technical problem that merely required the right “expert” solutions. Additionally, the West’s “Blank Slate” mentality—the belief that aid needs no analysis beyond comparative statistics and growth rates—came, he suggests, from the perpetuation of an “engrained but unexamined premise: that people in poor countries cannot be trusted to make their own decisions” and from our willful neglect of their histories.

Looking at the Past Can Help Us Understand the Present

In 2011, two Harvard economists published a study on the consequences of the slave trade, and found that slavery caused a lack of trust, which exists to this day. People living in the interior of West Africa show higher levels of trust compared to those living along the coastal regions where historically most slaves were captured.

People living in the interior of West Africa show higher levels of trust compared to those living along the coastal regions where historically most slaves were captured.

African slave trading states had not only become more powerful by using profits to import guns, they had also become more autocratic than areas that retained traditional councils of elders. Ethnic groups who had been victimized up until the early 1800s still had trouble trusting other ethnic groups. As Easterly points out in The White Man’s Burden, “Trust is very important for long-term prosperity and freedom … [and, unfortunately] … autocracy and violence breeds more lack of trust.”

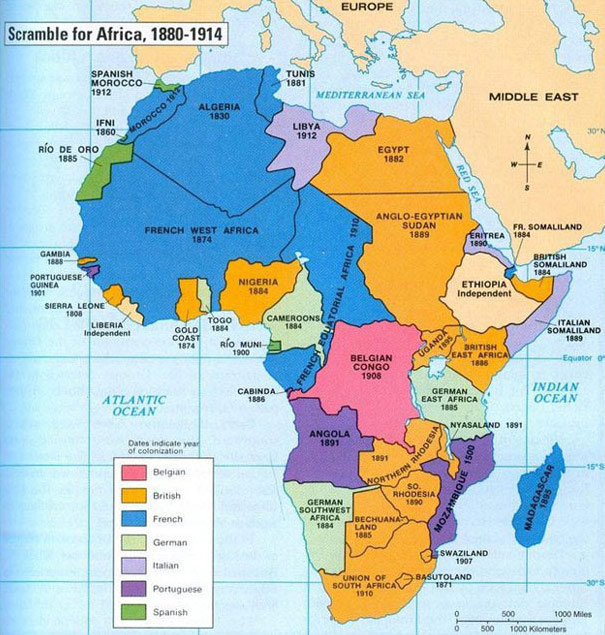

The Legacy of Colonialism

The demise of the slave trade and the growth of industrialization precipitated colonial expansion by European powers that sought raw materials, economic opportunity and preeminence through the acquisition of territories around the world. By the 1900s the majority of developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America were under colonial rule. The colonial administrations of Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, and Italy worked for their own interests, and the conflicts seen today are, too often, the result of their “top-down planning.”

At the Congress of Berlin in 1886 these European colonial powers drew the borders of African countries, creating artificial boundaries without regard for differences of race, tribe, religion, language, or for their long-term consequences. Sudan, for example, combined the Arab Muslims of the North and the Southern Africans, who practiced traditional African religions or Christianity, to create the largest country on the continent of Africa. Between 1899 and 1956 the British implemented a policy that favored the North, where they established a system of local administration known as “Indirect Rule,” maintaining pre-existing political leaderships and institutions. In contrast, they initiated a deliberate policy of “divide-and-rule” for the 60 or so indigenous ethnic groups speaking 80 different languages or dialects that constituted the South; an action which, of course, exacerbated tribal and clan differences.

At the Congress of Berlin in 1886 … European colonial powers drew the borders of African countries.

Unsurprisingly, when Sudan gained its independence in 1956 the Arab-dominated North was economically and politically very much stronger than the underdeveloped and weaker African south. The North took control and triggered the southern rebellion. Civil war broke out and lasted until 1972, with a hiatus of just over ten years, when war broke out again, this time complicated by the discovery of oil in Southern Sudan. President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir came to power after a military coup in 1989 ousted the democratically elected government of Sadiq al-Mahdi, which had begun negotiations with rebels in the South. Americans supported the government in the North, to the detriment of the South; and the West praised Sudan for its economic success in spite of its repressive Islamic dictatorship and the ongoing strife. From 2004 to 2005, 2.5 million people lost their homes and 400,000 died in Darfur at the hands of Arab militias. Today continuous civil war and drought means that almost 5 million people in South Sudan face starvation because they cannot find work or feed themselves.

And in the Middle East, amid the turmoil of World War I, the British and French allies, in anticipation of a successful outcome and the subsequent collapse of the Ottoman Empire, appointed Sir Mark Sykes and Monsieur Francois Picot to secretly divide up the Arab world. Though the British had sent T.E. Lawrence to the region with a promise of an independent Arab state in return for their support against the Ottomans, the real but unstated goal was to divide and secure the territory for their own purposes. In 1916 the two gentlemen came up with the now infamous Sykes-Picot Agreement. For control by the British they created Iraq, Transjordan and Palestine and for the French, Syria and Lebanon.

Though the Sykes-Picot intention was to divide the Levant on a sectarian basis, their newly created borders provided “straight line” divisions of the territories, because they were simpler for the French and British to administer. Of course, this entirely ignored sectarian, tribal and ethnic distinctions. The result was a gradual but decisive shift to nationalism away from anything resembling the colonialists’ form of governance; differences were buried in the struggle to get rid of European powers and replace them by Arab nationalism. As a consequence, militarist regimes dominated many Arab countries from the 1950s until the 2011 Arab uprisings.

The partitioning of India in 1947, which led to the creation of Pakistan, is another example of the damage done by imposing national boundaries in a haphazard manner.

Today, as we can see only too well, the different tensions and aspirations didn’t disappear, they just went underground to emerge again when strong, often brutal, leaders like Hafez Assad, Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi lost control of their countries.

The partitioning of India in 1947, which led to the creation of Pakistan, is another example of the damage done by imposing national boundaries in a haphazard manner. The plan did not take into account that Hindus and Muslims were intermingled throughout the large continent of India, so Muslims in one part had very little in common with those in another. This ignorance led to the Bangladesh War of Independence, that pitted East against West Pakistan and became one of the largest genocides in the twentieth century. A million people died and more than ten times that were displaced.

With their traditional checks and balances destroyed, many post-colonial chiefs were autocratic and corrupt.

In the post-colonial era (the late 1950s and early 1960s), leaders of the newly independent countries were euphoric as the end of colonial exploitation, slavery and human degradation finally arrived. They aimed at creating programs that would ensure their economic success, by increasing labor productivity and by efforts to add value to their agricultural products before marketing. But to achieve this, they needed foreign imports and technical assistance, which was excessively expensive and unsustainable.

With their traditional checks and balances destroyed, many post-colonial chiefs were autocratic and corrupt, using tax money and forced labor for their own benefit. Too often, politicians stirred ethnic hatreds to further their own agenda. Political parties, formed along ethnic and regional lines, fought for power and maintained it by repression and violence. Often protracted economic crises forced unpopular measures onto citizens, which exacerbated tribal differences, and led to political upheaval.

In the 1960s and 1970s, government after government on the African continent fell victim to a coup d’etat. Corruption, incompetence, and mismanagement drove economic instability, and no replacement—civilian or military—was able to solve a country’s political and socio-economic problems. More than one coup d’etat took place or was aborted during those decades in each of the following countries, all of which were previously under European colonial rule: Algeria, Benin, Burundi, Central African Republic, Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Madagascar, Mauritania, Morocco, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Uganda.

India failed to develop under British rule and, for the first three decades of independence, government planners didn’t do much better. It wasn’t until the 1980s, when two young entrepreneurs started the National Institute of Information Technology, that things began to change. Their program was such a success that new schools soon opened all over the country, enabling modern India to provide information technology outsourcing services to many top global corporations and new tech companies in-country.

Two colonies that did do well were Hong Kong and Singapore, but they had a number of unique things going for them. They were both strategically created as ports for trading and had no indigenous population, so relied on voluntary migration. The majority was Chinese, and, rather than boss or bully them, the British took over with permission from local rulers and then persuaded the Chinese merchants to settle: a move that stabilized free trade in the region.

In 1965 Singapore separated from Malaysia and became an independent democratic republic. Under the three-decade governance of its founding father Lee Kuan Yew and subsequently by his son, the country maintained political stability and was transformed from a colonial outpost to a developed modern economy, with meritocracy and multiracialism as the governing principles. Often criticized by the West for curtailing civil liberties, Lee maintained that these measures were necessary; he continued to serve his country for nearly 60 years until his death in 2015.

Another exception is Botswana. Botswana’s population is almost homogenous, with 79% the Tswana people. It was able to maintain strong pre-colonial institutions including political centralization, collective decision-making, and constraints on individual power. Unlike other African countries, Botswana’s institutions survived the colonial period intact and it quickly developed inclusive economic and political institutions, which enabled it to capitalize on its natural resources, maintain strong economic growth and establish a diversified economy. The Botswana government negotiated an agreement with De Beers that allows it to keep most of the diamond mining profits. When it gained independence in 1966, it was one of the poorest countries in the world, but since then Botswana has become one of the fastest growing.

The Consequences Today

Often the rich in these poor countries oppose democratic change because they fear redistribution.

So for many of the above reasons, underdeveloped countries often have weak, corrupt governments, which are difficult to change. Unscrupulous individuals rise to the top, resulting in a concentration of economic power in the hands of a small elite group perpetuated by political and economic institutions, which make them as wealthy as possible at the expense of society. Often the rich in these poor countries oppose democratic change because they fear redistribution. With no incentive to enforce property rights, provide basic public services, or encourage economic progress these countries can’t grow, and, not surprisingly, have significantly slower growth rates than those with democratic rule. Additionally, since political power is highly coveted, groups and individuals fight to obtain it, as evidenced by the civil wars and widespread lawlessness we’ve seen over the last four decades on the African continent.

It seems clear that a nation’s history has a great influence on its ability to develop. By the time these states became independent of colonial rule, their traditional structures and values had been neglected and ignored for too long. Colonial “Masters” left behind large institutional bureaucracies, which were not only alien to all these cultures, but had been created to serve colonial goals, vastly different from their own. For the most part, only elite, Western-educated individuals could imitate them, perpetuate their institutions and take control; which they did, often at the expense of their own populations.

[The justice system and law enforcement were] not designed by colonials to stop crime or protect the people, but to protect themselves and their government from the people.

These institutions exist to this day, with their negative effects. One major example with devastating repercussions is seen in the justice system and law enforcement. These were not designed by colonials to stop crime or protect the people, but to protect themselves and their government from the people. Unfortunately, while the last 50 years has seen great strides in the ability of human rights organizations to embed laws of equality and justice in these countries, their colonial systems of law enforcement have never been reengineered to actually enforce them. As a consequence, according to a 2008 UN study, 4 billion people live outside the protection of the law:

This Commission argues that four billion people around the world are robbed of the chance to better their lives and climb out of poverty, because they are excluded from the rule of law. Whether living below or slightly above the poverty line, these men, women, and children lack the protections and rights afforded by the law. They may be citizens of the country in which they live, but their resources, modest at best, can neither be properly protected nor leveraged. Thus it is not the absence of assets or lack of work that holds them back, but the fact that the assets and work are insecure, unprotected, and far less productive than they might be. There are further vulnerabilities, as well. Indigenous communities may be deprived of a political voice and their human rights violated. In addition to exclusion based on their poverty and their gender, poor women may also be denied the right to inherit property. In our own era then, vast poverty must be understood as created by society itself.

And four years later the UN Chronicle stated that:

Historically, global decision makers neglected the rule of law when deciding on development policy. Indeed, the rule of law is notably missing from the biggest global agreement designed to end extreme poverty and promote development: the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which will draw to a close in 2015. The MDGs, while successful in many ways, have failed to live up to some of the key hopes expressed in the United Nations Millennium Declaration (2000), the seminal UN text from which the goals emerged. The Declaration saw the “central challenge” for the world as ensuring that “globalization becomes a positive force for all the world’s people.” Since 2000, however, globalization has not been, as the Declaration hoped, “fully inclusive and equitable.” Instead, the gap between the rich and the poor continues to widen, xenophobia and discrimination are on the rise, and multiple financial crises around the globe are driving families into poverty and despair. The rule of law—realized through efforts to ensure access to justice for all—can be a steadying force amid all of this turmoil.

As the world started to contemplate a post-2015 development vision, the General Assembly in its September 2012 Declaration on the Rule of Law at the National and International Levels revisited this omission in the original MDGs. This Declaration represents a major opportunity to bring the high level policy on the rule of law to those people who need it most. States should now consider how the rule of law might feature in the post-2015 agenda—whether as a stand-alone goal on access to justice, as a target within a broader goal or as an indicator across all post-2015 goals.

“Simply put, if people aren’t safe, nothing else matters. Shipping grain to the poor, helping them vote, or assisting their efforts to start a farm is irrelevant.”

While the Millennium Development Goals did not address issues of violence or law enforcement reform, the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals explicitly include these through Goal 16, which focuses on peace, justice, and strong institutions.

Gary Haugen and Victor Boutros’s book The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence focuses on this central role of violence in perpetuating poverty, and shows that if any headway is to be made, this issue has to become a top priority for policymakers. “Simply put,” they say, “if people aren’t safe, nothing else matters. Shipping grain to the poor, helping them vote, or assisting their efforts to start a farm is irrelevant.”

Of course, Western aid organizations were able to connect with these post-colonial institutions and their leaders, the majority of whom believed modernization inevitably meant Westernization. A further look at the history of aid and the role it plays today may help us understand the function of these organizations today.

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Thomas Piketty

A leading economist documents the trend of income inequality through history, stressing that the way an economy functions is directly related to a power structure that is determined and maintained by the few who hold the wealth.

In the series: Ending Global Poverty

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

The “Bottom Billion” People

Economist Paul Collier, TED

Around the world right now, one billion people are trapped in poor or failing countries. How can we help them? Economist Paul Collier lays out a bold, compassionate plan for closing the gap between rich and poor.

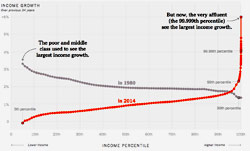

Our Broken Economy, in One Simple Chart

David Leonhard, New York Times

Three leading economists provide a dramatic look at the skyrocketing income growth of the 0.01% very rich vs. all other Americans over the past 34 years.