Your ZIP Code May Be Hazardous to Your Health

How long you live may be determined by your zip code at birth …and a number of other social determinants.

The implementation of population-level improvements in vaccination, access to safe water, food and sanitation get the “biggest bang for the buck,” quite literally.

Life expectancy has long been observed to reflect the robustness of our public-health system. But the increase in life expectancy between 1800 to 1990 was driven by decreases in extreme poverty – until by 1981, those living in extreme poverty had dropped to 44%, and today, only 10% of the global population lives in extreme poverty with an average life expectancy of 64 years – but that’s still almost a billion people.

It is important to acknowledge that this dramatic decrease in extreme poverty and its resultant increase in life expectancy and better health did not occur everywhere in the world and it was not a product of modern healthcare as we know it today. It was the industrial revolution that improved the income level of many, many individuals and enabled the expansion of public-health basics such as safe water, sanitation, housing, adequate food resources and the development of vaccines against the infectious diseases that once killed millions.

Some places in the US are associated with a far lower life expectancy than average. In 2021 the US had the lowest life expectancy, 79.1 years, of any of the larger, wealthy countries but spent twice as much on healthcare.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. As such, health is strongly influenced by what are known as the social determinants of health:

- Income level

- Education level

- Access to safe food and drinking water

- Sanitation

- Freedom from environmental pollution

- The presence of a fair and just judicial and democratic political system

- Access to health care – particularly vaccinations and maternal and child health interventions

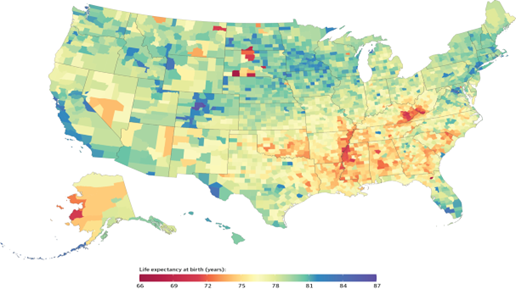

However, in the first decade of the 21rst century, in spite of a seemingly booming economy, US increases in life expectancy lost ground – but not for everyone. Some places in the US are associated with a far lower life expectancy than average. In 2021 the US had the lowest life expectancy (79.1 years) of any of the larger, wealthy countries but spent twice as much on healthcare. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2017 looked at life expectancy at the county level and found that life expectancy at birth was 79.1 years overall but differed by 20 years between the counties with the lowest and highest life expectancy. The most significant decreases in life expectancy were found in several US counties in N & S Dakota, eastern Kentucky, southwest West Virginia and along the lower half of the Mississippi.

“Inequalities in Life Expectancy Among US Counties,1980 to 2014: Temporal Trends and Key Drivers”, Laura Dwyer-Lindgren; Amelia Bertozzi-Villa; Rebecca W. Stubbs; Chloe Morozoff; Johan P. Mackenbach; Frank J. van Lenthe; Ali H. Mokdad; Christopher J. L. Murray. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1003-1011. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0918

Published online May 8, 2017.

Inequalities in Life Expectancy among US Counties, 1980 to 2014: Temporal Trends and Key Drivers

Life Expectancy at Birth by County, 2014.

Counties in South Dakota and North Dakota had the lowest life expectancy, and counties along the lower half of the Mississippi, in eastern Kentucky, and southwestern West Virginia also had very low life expectancy compared with the rest of the country. Counties in central Colorado had the highest life expectancies.

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association

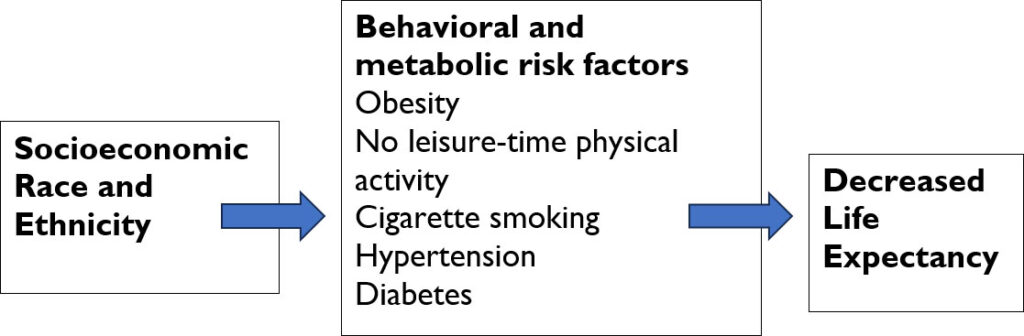

This same study attempted to identify what factors might be associated with such a dramatic difference in life expectancy. It looked at socioeconomic and race/ethnicity factors, behavioral and metabolic risk factors, and healthcare factors. The study found that the influence of socioeconomic and race factors on life expectancy was largely mediated by 5 behavioral and metabolic risk factors: diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, smoking, and no leisure time physical activity.

How can the effects of socioeconomic and race/ethnicity on life expectancy be mediated by behavioral and metabolic risk factors, a cluster of risks associated primarily with heart and blood-vessel diseases?

In part it’s due to what these neighborhoods can or cannot provide to those living there: choices between unhealthy and healthy options. For example, the unhealthy counties may offer more fast-food options than large grocery store chains offering fresh fruits and vegetables. Higher calorie but nutrient-poor food leads to obesity and diabetes and is the hallmark of ultra-processed foods found in the fast-food industry. Lower taxes on cigarettes and/or no smoking restrictions also make this addictive lifestyle choice more accessible. Inadequate or underfunded schools lead to lower educational expectations and attainment. And these areas have an increasingly older and poorer population and a larger proportion of black, brown and/or indigenous populations. They might also provide fewer safe, walkable green spaces and sidewalks, limited public transportation, and limited access to healthcare because of scarce clinics or hospitals, and less medical insurance because of reduced expansion of Medicaid services.

But not all rural residents are affected equally. Among all races in rural areas, American Indians/Alaska Natives have the highest rates of physical inactivity due to physical, mental, or emotional problems (28.5%); Hispanic individuals have the lowest rate of healthcare coverage (61.1%); Non-Hispanic Whites have the highest rates of binge drinking (16.3%); and Black individuals have the highest rates of obesity (45.9%) (“The Southern Rural Health and Mortality Penalty: A Review of Regional Health Inequities in the United States,” Charlotte E. Millera, Ramachandran S. Vasana, Soc Sci Med. 2021 January; 268:113443).

We have known about this health disparity for several decades now but little has been done in the affected states to address the underlying issues.

External Stories and Videos

Survival of the Richest

Oxfam Briefing Paper, 2023

How we must tax the super-rich now to fight inequality.

Watch: Coronavirus Is Our Future

Alanna Shaikh, TEDx

Global health expert Alanna Shaikh talks about the current status of the 2019 nCov coronavirus outbreak and what this can teach us about the epidemics yet to come.

Watch: The Next Outbreak? We’re Not Ready

Bill Gates, TED

In 2014, the world avoided a global outbreak of Ebola, thanks to thousands of selfless health workers — plus, frankly, some very good luck. In hindsight, we know what we should have done better. Now’s the time to put all our good ideas into practice, from scenario planning to vaccine research to health worker training.

Watch: How We must Respond to the Coronavirus Pandemic

Bill Gates, Chris Anderson & Whitney Pennington Rogers, TED

Bill Gates offers insights into the COVID-19 pandemic, discussing why testing and self-isolation are essential, which medical advancements show promise and what it will take for the world to endure this crisis.

Sustainable Development Goals Progress Report

United Nations

A snapshot of global and regional trends towards the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals as of September 2019.

Dollar Street

Gapminder.org

Imagine the world as a street. All houses are lined up by income, the poor living to the left and the rich to the right. Everybody else somewhere in between. Where would you live? Would your life look different than your neighbors’ from other parts of the world, who share the same income level?

Maternal and Child Health

Childbirth can be a risky experience for women, especially in developing countries where 99% of all maternal deaths occur. Women in poorer countries are 27 times more at risk of dying from pregnancy, childbirth, or immediate post-partum complications than women in developed countries.

Current and Future Challenges

Deaths from diseases such as heart attacks, strokes, diabetes, and injury; the growing shortage of health workers; and the inevitable increase in population displacement all have an outsized impact on the poorest countries. What can be done?

The Status Syndrome

How Social Standing Affects Our Health and Longevity

Michael Marmot

In this seminal study, the renowned British epidemiologist Michael Marmot shows that the lower in a socioeconomic hierarchy a person is ranked, the worse is that person’s health—a maxim that holds for almost any disease or health risk factor. Those who stand higher up on the ladder of life are always healthier than those even a few steps below. It’s not poverty that makes the difference, says Marmot, but inequality—where one stands in the hierarchy.