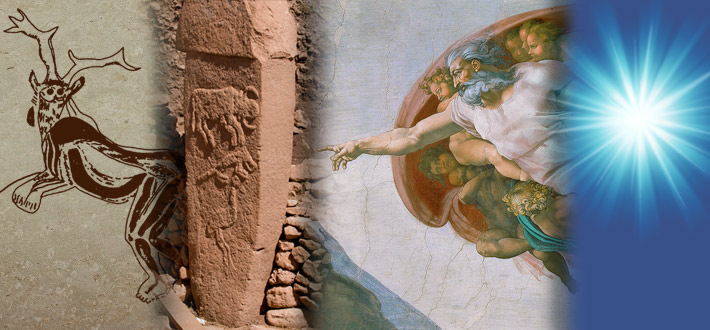

Connecting with the Gods

The relationship between people and their god(s) was of primary importance all over the world. As populations grew, settlements became cities. Order was achieved through religious hierarchy—priests and leaders ensured that they had access to “secrets” using religion to stay powerful.

Neolithic Era

Cosmic and Terrestrial Maintenance

A huge communal effort by humans to maintain cosmic and terrestrial harmony shaped the Neolithic Revolution. Also known as the Agricultural Revolution, this period marked the start of organized religion, agriculture, and science.

Death and Transcendence

In the Neolithic period, shamans became the specialists in transcendence. The stability of the community rested on their ability to engage the whole group by connecting it to the spirit world. How did they do this?

Neolithic Architecture: Replicating the Cave Experience

Unlike their prehistoric ancestors, Neolithic shamans no longer had to rely on the natural topography of each cave to fashion their sacred art. Instead, they designed and built structures that repeated the cave experience.

Neolithic Beliefs and Customs Migrate West

During the Neolithic era, as land became exhausted, people were obliged to move to newer pastures. They traveled not only with their families but also with their animals, and, most importantly for us, with their customs and beliefs.

Megalithic Temples of Malta: A Scientific Breakthrough

At the foot of Sicily are two islands, Malta and Gozo, where more than 23 megalithic temples once stood. The construction of these temples spanned over a thousand years of continuous building and elaboration.

Britain's Megalith Building Boom

In Britain, about 1,300 Neolithic mega-sites appear to have been built within little more than a century.

Pyramids: Stairways to the Gods

Pyramid-shaped structures are yet another example of how human beings expressed their psychological understanding of our place in the universe as three-tiered.

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia: “The Land Between Two Rivers"

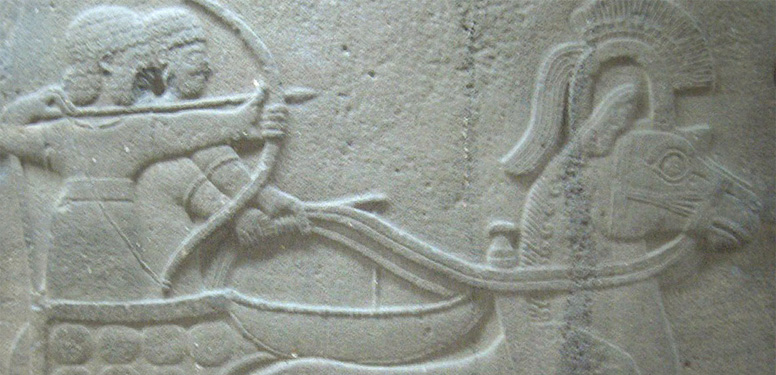

Part of the Fertile Crescent, Mesopotamia (“the land between two rivers” in Greek), was by its geographical location and development influential in the region from at least 2500 BCE to the fall of Babylon in 539 BCE.

Mesopotamian Worldview and Beliefs

The ancient Mesopotamians believed that their fates hinged on the whims of the deities, demons, and gods that ruled over them.

Ziggurats: Connecting Heaven and Earth

The ziggurat, the “mountain of God” or “hill of Heaven” was the center of the temple complex. Built of clay bricks, it was a massive, solid, pyramidal stepped structure, the summit of which housed the God.

Marduk and the Early Signs of Monotheism

During the reign of Hammurabi in the 18th century BCE, Babylon became the principal city of southern Mesopotamia, and the patron deity of Babylon, the god Marduk, was elevated to the level of supreme god.

Ancient Mesopotamian Literature and Sacred Texts

Mesopotamian scribes published a body of legends, epics, and sacred literature on cuneiform tablets, like the ‘Enuma Elish’ and ‘The Epic of Gilgamesh’, that were to influence later civilizations.

Understanding Cuneiform Tablets and Writing

From their cuneiform writings on clay tablets scholars know that the Mesopotamians, like the later Greeks, attempted to understand their world and the universe in any way they could.

Noble Ones

The Noble Ones

The Aryans or “Noble Ones” were thought to have remained together on the Caucasian steppes from about 4500 BCE until about 2500 BCE when groups began to migrate.

Indus-Sarasvati Civilization

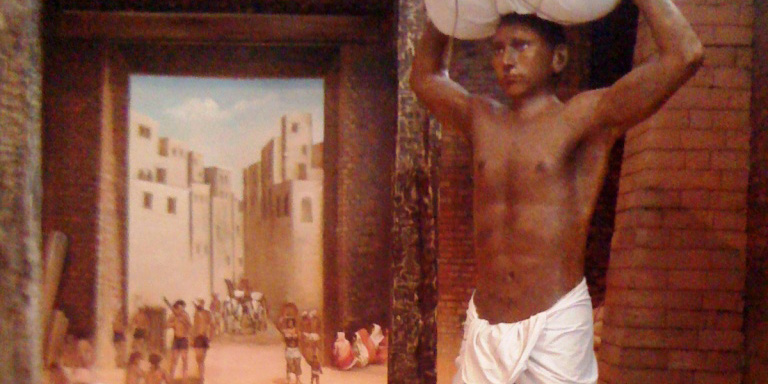

Indus-Sarasvati Civilization

By 2500 BCE the Indus-Sarasvati or Harappan civilization became the largest civilization of the Ancient world, extending over more than 386,000 square miles across the plains of the Indus River from the Arabian Sea to the Ganges.

Mehrgarh (7000–2000 BCE)

The Neolithic site of Mehrgarh is located to the west of the Indus-Sarasvati flood plain, in Baluchistan east of the mountain city of Quetta in Pakistan.

Harappa (3500–1900 BCE)

The ancient city of Harappa, situated on a tributary to the Indus River in Pakistan, grew into a bustling settlement. Damage under British colonial rule and looting by local people likely set back our knowledge of this civilization.

Mohenjo-Daro (2600–1900 BCE)

Located between the two vast river valleys of the Indus and the Sarasvati, Mohenjo-Daro was one of the most important cities of the Indus civilization.

The Demise of the Indus Civilization

By about 3,900 years ago (1900 BCE), the monsoons had shifted east causing the Sarasvati to gradually change from a perennial to a seasonal river. This and other challenges caused the Indus civilization to decline.

Indus-Sarasvati People: Who Were they? What did they Believe?

We know almost nothing of the Indus-Sarasvati people or their religion. Speculations on the meaning of figurines, depictions on seals, etc., are just that.

Aegean Neolithic and Bronze Age Civilizations

The Cycladic Civilization Circa 3300 to 1100 BCE

The beginnings of a material culture in Greece took shape in a cluster of 30 small Aegean islands in the Neolithic and early Bronze Ages. Together they are known as the Cyclades, from the archaic Greek word kyklos, meaning “cycle.”

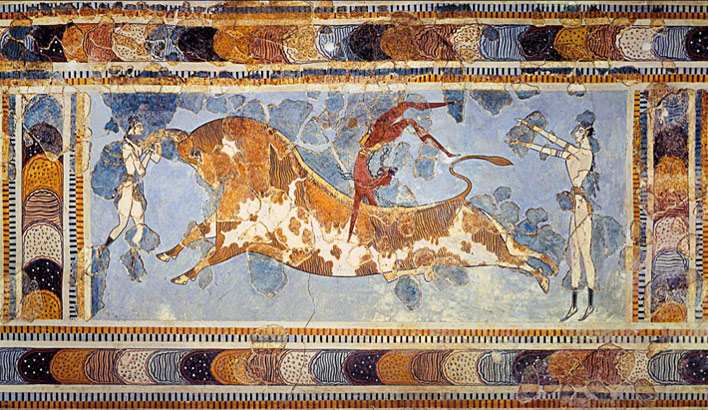

Minoa–Europe’s First Civilization ca 2000–1400 BCE

Crete sits at the crossroads of Africa, Asia, and Europe and was the hub of a cosmopolitan world that included Egypt, the Levant, Anatolia, and the Greek mainland.

Minoa “Palaces” and Religious Beliefs

In 1900, the famed archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans provided the first evidence of an extraordinary civilization. He named it Minoan, after the legendary King Minos, son of Zeus.

Conflict and Calamity

Earthquakes, often severe and ruinous, were frequent in Minoan times.

The Mycenaeans 1600–1100 BCE

The Mycenaeans were closely related to the Minoans - both descended from early farmers who lived in Greece and southwestern Anatolia.

The Bronze Age Collapse

The First Global Economy

Could a series of catastrophes over a century or more, have led to the final collapse of the Bronze Age civilizations in the Aegean, Egypt, and the Near East after nearly two thousand years of growth and prosperity?

The Dark Ages

After nearly two thousand years of growth and prosperity, (ca 3000–1200 BCE) the civilizations in the Aegean, Egypt, and the Near East unraveled. What happened?

The Perfect Storm

Is what happened in the ancient world over 3,000 years ago likely to happen again, but on a much larger scale?

Archaic Greece

Archaic Greece: The Dark Age and a New Dawn

Evidence of very early settlement on the Greek Islands comes from the Franchthi cave, overlooking the Argolid Sea in the Peloponnese.

Emerging from the Dark Age 800–500 BCE

Statis or conflict was a continuous and ever-present condition in the steps towards the polis or city-state—the political community which would become characteristic of Greece.

History According to the Storytellers

With no first handwritten documents of their past, survivors turned to traditional storytellers.

Religious Life

Like other pre-Axial cultures, Greeks believed in a pantheon of Gods who presided over every aspect of life and nature.

Ancient China

Early Civilizations China

Chinese civilization dates back 5,000 years to mythical and legendary individuals who ruled the fertile Yellow River valley of what we know today as China.

Three Legendary Sovereigns

Three Sage Kings, or Three August Ones, were said to be god-kings or demigods. Because of their superior virtue they lived to a great age and ruled over a long period of peace.

The Five Emperors

The Five Emperors may be thought of more as supreme beings, rather than “emperors.” They were morally perfect.

The Shang Dynasty 1600–1045 BCE

Historians note that the Shang dynasty was itself believed to be mythological until written evidence was found in the 1920’s.

The Unseen World: The Rise of Gods and Spirits

The Institute for Cultural Research

“As the problems and challenges facing humankind have changed, so have their religious and ideological solutions. We live among the wreckage of once-potent solutions. If we neglect them, they may become barriers to thought and action. If we understand them, they are a treasure house for all of us to share.”

The Unseen World: The Rise of Gods and Spirits

The Institute for Cultural Research

A Contemporary Look at the Nature of Religious Experience

Review by George Kasabov

Contributing Writer

People can persuade themselves of anything. Many believe that death is a transition to a transcendental world, that miracles occur through the will of God, or that our lives are ruled by immaterial spirits. How is it that, in our scientific age, when we have learned so much about the evolution of the universe and the nature of life, so many still cling to such beliefs? Why is it that faith – belief in the unprovable – is considered a virtue?

Returning to the Spirit in “Sacred Nature”

A review of Sacred Nature by Karen Armstrong

A staggering 33 million people have been internally displaced in Pakistan. Because climate change is likely to have played a role in the heavy rains, the displaced can be considered “climate refugees”— a term that the novelist Fatima Bhutto urges us remember, as we will all be impacted by climate change, and many of us will become migrants as a result, if we haven’t already.

Religious Evolution and the Axial Age

From Shamans to Priests to Prophets

Hardcover edition 2018

Reported by Sally Mallam

Contributing Writer

Why are there are so many different types of religion and how and why has religion evolved over time? The answer lies in both our biological and our sociocultural evolution.

In the series: Ideas that Shaped Our Modern World

- Paleolithic Beginnings

- Axial Age Thought

- Jesus: Origins of Christianity

- Muhammad: Origins of Islam

- The Journey of Classical Greek Culture to the West

- Stories and Storytelling

- A Contemporary Look at the Nature of Religious Experience

- Returning to the Spirit in “Sacred Nature”

- Religious Evolution and the Axial Age